Science tells us tai chi is good for both body and mind

By Wendy Haaf

Illustration: iStock/Eloku.

In 1994, Pat Bradley-White, then 47, happened to hear a brief description of tai chi on a radio program. “That got me curious and interested,” she says, so she sought out classes to give the ancient practice a try.

Variously described as meditation in motion and a martial art practised for both its defence-training and health benefits, tai chi is at least 700 years old and involves a sequence of 108 deliberate dancelike movements, or “forms” (which incorporate a synchronized system of breathing), gentle enough that they can be performed by people with a variety of health challenges.

Enjoying both the activity and the fellowship she found in the classes, Bradley-White, who now lives in Almonte, ON, continued the practice and over time began noticing that the niggling aches and pains in her knees and back were fading.

“Tai chi creates an awareness of what’s going on in your body, and it changed the way I moved,” she says. “Once I did tai chi regularly, the aches and pains disappeared. My balance was better and my leg strength got better.”

And while Bradley-White says she wouldn’t have described herself as feeling particularly stressed before taking up tai chi, as she progressed, she felt a previously invisible weight lifting. Moreover, she says, “My memory started to improve.”

While there are a number of styles of tai chi named for the families that purportedly established each of them—such as Sun and Yang—the differences mostly come down to pace and emphasis—for instance, whether the goal is self-defence or breathing and relaxation.

Bradley-White practises a modified form of the Yang style that focuses on improving health and is rooted in Taoist values, such as volunteerism. Known as Taoist tai chi, the variant was developed by Master Moy Lin Shin, who began teaching it soon after arriving in Canada in 1970. He also established the Fung Loy Kok Institute of Taoism, a now international organization that is entirely volunteer-run.

Since all styles incorporate similar physical and mental elements, it’s reasonable to expect similar effects on the body and mind. Here are just a few of the reasons it’s a great form of exercise that’s particularly well-suited for those of us 55 or older.

Nearly anyone can do it.

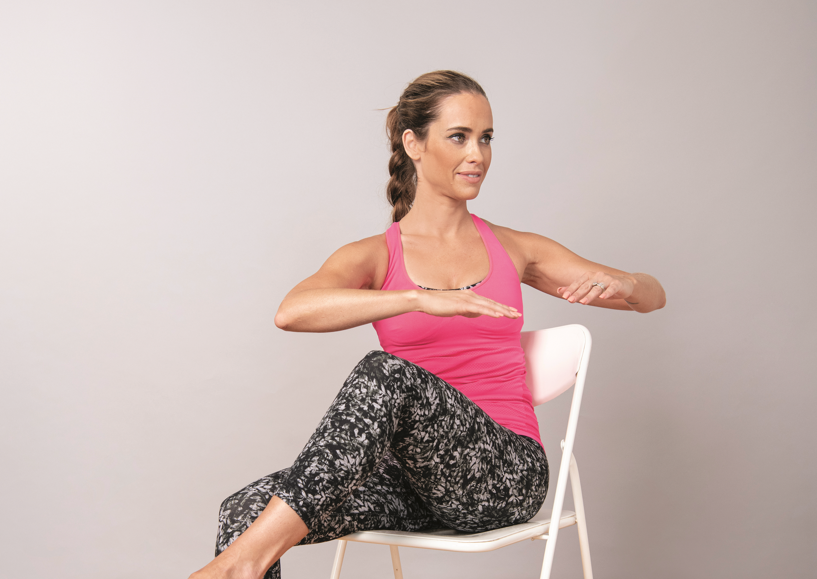

We know there’s more and more evidence that exercise can help preserve our physical and mental function as we age and improve conditions ranging from high blood pressure to depression, but even walking can be difficult if you have certain chronic conditions. Tai chi, however, “is very adaptable,” says Mirella Veras, a physiotherapist with Coastal Sports and Wellness in Halifax, tai chi instructor, and author of Evidence-Based Tai Chi for Rehabilitation and Wellness (2018). For example, a chair can be used as a support when necessary. And since it doesn’t involve impact and “you kind of lock your knee when you’re standing,” it puts minimal stress on the joints, Veras says.

On the other hand, “for people who want something more challenging and demanding, it can offer that, as well,” says Margaret Powell, an occupational therapist, psychotherapist, and volunteer instructor with the Toronto branch of the Fung Loy Kok Institute of Taoism. “It’s like weightlifting: you can be an Olympic weightlifter or lift one-pound weights.”

It’s helpful for a variety of health problems.

The scientific community has been curious about the link between tai chi and better health. People with a variety of physical limitations due to health problems such as fibromyalgia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have been recruited to participate in classes as part of research studies, and a number of trials suggest that tai chi has positive effects on many such conditions.

For instance, a review conducted by University of British Columbia researchers found that regular practise (typically two to three weekly sessions over about 12 weeks) improved pain and stiffness, knee strength, and physical performance measures such as sit-to-stand times in people with osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee. A separate review, released by The Cochrane Collaboration in 2015, concluded there is moderate-quality evidence that, in people with OA, tai chi improves knee pain and physical function to a degree that’s comparable to estimates reported for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication.

In a study involving 195 people with Parkinson’s disease that was published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2012, tai chi reduced falls (a hazard of Parkinson’s due to changes in gait) and outperformed resistance exercise in improving stability and stride length, both of which are impaired by the disease. Another paper, published in The BMJ in 2017, combined findings from 18 trials involving older adults and concluded that tai chi was effective at preventing falls and that the preventive effect was likely to increase the more one practised the exercises.

A comprehensive review of the literature on the benefits of tai chi in 25 separate conditions that appeared in the journal Canadian Family Physician in 2016 concluded that there’s excellent evidence that it improves balance and aerobic ca-pacity, prevents falls, eases the pain and stiffness of OA, improves mobility and balance outcomes in people with Parkinson’s disease, decreases breathlessness in people with COPD, and improves cognitive capacity in older adults. The review also said that there’s good evidence of benefit in depression, cardiac and stroke rehabilitation, lower-leg strength, and dementia, as well as fair evidence that tai chi increases overall well-being and improves sleep. Consequently, the authors concluded, “Physicians can now provide evidence-based recommendations to their patients about tai chi.” (Of course, the authors added the standard caveat: “As with any other exercise program, ongoing medical follow-up for any clinical condition is indicated.”)

It’s a good full-body exercise.

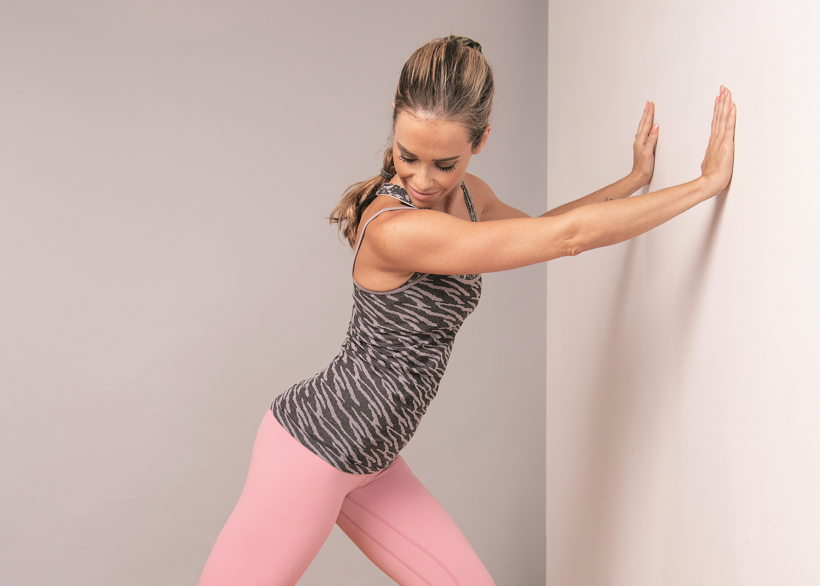

Not only does tai chi work the whole body, but it strengthens the core and improves posture (both of which are helpful for preventing and treating back pain), and it combines both flexibility and stretching elements with strength training, using one’s own body weight and gravity for resistance. Since the postures are done while standing, it’s also a weight-bearing exercise and, as a result, likely “improves your bone density,” Veras says.

Tai chi bolsters balance and stability and prevents falls (at least in part) because, Veras says, “we learn to transfer our weight from one side to the other and from front to back.” In addition, “We work a lot on breathing; that’s why it improves pulmonary function.”

There are indications that the sustained practice of tai chi may foster fitness to an extent similar to that resulting from somewhat more strenuous forms of exercise. In a 2018 Time article, Dr. Michael Irwin, who has conducted a number of studies on tai chi, noted: “Over time, we see people who do tai chi achieve levels of fitness similar to those of people who walk or do other forms of physical therapy.”

Five systematic reviews and two trials support the notion that tai chi acts as an endurance exercise, providing what the authors of a Canadian study published in the journal CMAJ deemed excellent evidence that it improves aerobic capacity, especially in previously sedentary people. And a 2013 study published in American Journal of Epidemiology “found that tai chi was almost as effective as jogging at lowering the risk for premature death in older men” over a five-year period, Veras says.

Some research suggests the practice may even have beneficial effects on the immune system, revving up the response to a shingles vaccine and lowering levels of proteins that act as markers for the type of potentially damaging inflammation associated with an increased risk for heart attack.

It’s a mind-body therapy.

While mindfulness meditation has been linked with benefits ranging from reductions in stress and adherence to health-promoting behaviours to increased density in a region of the brain that’s involved in memory, some people find it unappealing, difficult, or uncomfortable.

“I don’t do very well with meditation because I have a chattering brain,” says Toronto’s Margaret Powell. In tai chi, however, the concentration involved in getting the forms just right “allows our mind to focus only on the movements—not on our grocery list, not on the worries in our lives,” she explains. As Pat Bradley-White of Almonte, ON, puts it, “Having to let go of all your other thoughts gives you a break.”

That rootedness in the present moment may mimic what happens in the brain during meditation. For instance, Powell has a biofeedback headband that purportedly measures brain activity to help guide meditation practise. She says that while the device’s readings reflected her difficulties with meditation, “when I put it on and did tai chi, the readings I got showed me to be in a solid meditative state, even though I was moving my body.”

While it’s hard to say whether it’s this effect on the brain, the physical exercise, the social aspect, or the combination of all three that’s responsible, tai chi seems not only to support healthy aging but to help people get through physically, mentally, and emotionally arduous experiences.

“There have been 22 studies published in the journal Cancer showing benefit in different psychological symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, and quality of life, and also specific symptoms, such as fatigue, sleep, and pain,” says Linda Carlson, the Enbridge Research Chair in Psychosocial Oncology and a professor in the Department of Oncology at the University of Calgary’s Cumming School of Medicine. (Carlson is one of the lead investigators of a study that will compare tai chi with mindfulness meditation in cancer survivors. See “MATCH Study,” below.)

Powell says she saw similar results in a small research study she and a fourth-year sciences student conducted in association with Sheena’s Place, a Toronto community centre for people with eating disorders. “People with severe eating disorders came in once a week and did an hour-and-a-half introductory class in Taoist tai chi,” she says, “and at the end, their depression levels had improved by 25 per cent.”

It can foster social connections.

Meeting new people with a shared interest is one way of fostering social connections, which research has tied to longevity and overall health and well-being in older adults.

“People make new friends. I always say that we build the tai chi family,” Mirella Veras says.

Taoist tai chi also builds in an element of volunteerism (not only within the organization, but also through community outreach), which itself is linked with a number of benefits, such as improvements in cognitive function and overall sense of well-being.

“Everybody has to jump on board and help,” Powell says. “Then they feel vital, they feel essential, they feel that they’re really contributing.

Now an accredited instructor with the Fung Loy Kok Institute of Taoism, Pat Bradley-White, like all of her colleagues, teaches on a volunteer basis. “Everybody teaches to share the benefits they’ve experienced personally,” she says. “I think that’s unique and very powerful.”

MATCH Study: Tai Chi and Cancer

MATCH Study

“We know that different mind-body therapies are beneficial compared to nothing or usual care” in cancer survivors, says Linda Carlson, the Enbridge Research Chair in Psychosocial Oncology and a professor in the Department of Oncology at the University of Calgary’s Cumming School of Medicine. “But the nuance of what type of intervention is going to be beneficial for which outcomes, which symptoms, and what kind of patient…we really don’t know too much about that.”

A new study, in which Carlson is one of the principal investigators, will try to tease apart some of those factors. Called MATCH (Mindfulness And Tai chi for Cancer Health), it’s being conducted jointly by the University of Calgary and its affiliated Tom Baker Cancer Centre and the University of Toronto and its affiliated Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. People will participate in classes in either mindfulness or a simplified version of tai chi, depending on their preference; those who have no preference will be assigned randomly to one or the other. For more information, including a list of eligibility criteria, visit thematchstudy.ca.