Here’s what you can do to help keep your aging brain young

By Wendy Haaf

If you ask Canadians what needs to be addressed to improve health care, research on how to maintain brain health as we age ranks high on the list. According to a September 2020 national survey by Toronto’s Baycrest Health Sciences, 90 per cent of respondents (93 per cent of those 55 or older) ranked dementia as a leading area of concern, second only to residential care.

Clearly, maintaining a healthy brain is top of mind for most who are past the half-century mark and concerned with remaining engaged and independent for as long as possible. While the quest to cure Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias has so far come up empty, researchers have learned a good deal about what can preserve and even improve the function of what is arguably the body’s most important organ. In fact, in recent years, research has revealed that even later in life, certain types of activity can coax new brain cells into being, forge new networks of connections between those cells, and immediately improve performance on certain cognitive tests. That is, the brain remains plastic—defined as the ability to adapt specific areas and functions to new circumstances.

“When I went to school, the general idea was that plasticity was happening from when you were born until the teenage years, and then it was pretty much frozen,” explains Claude Alain, a senior scientist at Baycrest’s Rotman Research Institute and a professor at the University of Toronto’s Department of Psychology and its Institute of Medical Science. “But now we have data that there’s still quite a bit of plasticity as you get older.”

Fortunately, some of the factors that can help keep the brain in the best possible shape are within our control.

Prevent chronic conditions.

“When we think about dementia or mild cognitive impairment, we often think of older adults, but in reality, we know that a lot of the precursors occur much earlier,” says Teresa Liu-Ambrose, a professor in the University of British Columbia’s Department of Physical Therapy and the director of the Aging, Mobility, and Cognitive Neuroscience Lab. The seeds of some of the health issues that increase the likelihood of later developing dementia begin sprouting before we hit 55. “Mid-life is when most of us start presenting with risk factors for chronic conditions such as prediabetes and prehypertension,” Liu-Ambrose says. Even when these metabolic abnormalities haven’t yet progressed enough to qualify as full-blown diagnoses, “we can observe subtle changes in the brain.”

When it comes to the healthy habits that can potentially prevent such conditions or push them into remission, “the earlier you start, the better,” Liu-Ambrose says.

Manage medical issues.

Even though it’s not always possible to ward off such health issues entirely, getting them under control using medications and prescribed non-drug therapies can help keep your brain sharp. One example is hearing loss, “a cause of cognitive decline in seniors,” says Jed Meltzer, a scientist at the Rotman institute and an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Toronto. “It causes isolation and a decrease in cognitive and social stimulation,” all of which have been linked with negative effects on brain function. However, treatment, including hearing aids and strategies for improving communication, “is quite effective at improving people’s outcomes,” Meltzer says.

Head off head trauma.

“A head injury can predispose you to a higher risk for dementia later in life, even years after the injury and even if you recovered from the injury at the time,” Meltzer observes. Consequently, it’s important to do everything you can to protect yourself. In addition to the obvious—wearing a helmet when participating in activities such as cycling—protection includes taking the necessary steps to prevent falls, which can range from removing tripping hazards such as area rugs and ensuring that hallways are well-lit, to having your vision checked regularly and choosing winter footwear with good traction. (Scientists at the research facility Winter-Lab, part of the University Health Network’s Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, have created an online tool to help with that last chore: ratemytreads.com.)

MIND your eating style.

“There’s more and more data to suggest that having a healthy diet later in life can help you maintain cognitive function,” Alain says.

For example, in a 2017 study that followed 960 people aged 58 to 99 who had been enrolled in a memory and aging study for an average of 4.7 years, the group (one of five) who ate the most leafy green vegetables (an average of 1.3 servings a day) scored much higher on cognitive assessments than did the group who consumed the least, performing as well as someone 11 years younger.

Similarly, a 2015 study that tracked 960 adults (average age: 81.4) over 4.5 years found that people whose diets most closely conformed to a hybrid of the Mediterranean and DASH diets (known as the MIND diet, short for Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) were 7.5 years “younger” cognitively than were participants with eating plans that differed most from this pattern.

There’s also evidence that even if your eating habits have been less than exemplary before age 50, adopting a diet similar to the MIND diet can keep your brain young. For example, the panel of experts who created the Canadian Brain Health Food Guide based their recommendations on studies in which, four months after switching to such a diet, participants had “performed as if they were nine years younger on tests of reading and writing speed”; four years later, subjects had yet to experience memory loss. (While similar to the Mediterranean diet, the diet espoused in the Canadian Brain Health Food Guide is based on specific amounts of certain foods: fish, berries, and cruciferous vegetables three times weekly; green leafy vegetables and nuts—including four servings of walnuts—once daily; and legumes at least twice a week. For a copy of the guide, visit baycrest.org, click on the tab for “Menu” at the top right, and type “brain health food guide” in the search bar.)

Get sufficient sleep.

“Sleep is coming up more and more as a critical factor” in protecting the brain, Liu-Ambrose says. “There’s been some interesting research to show that even after one night of what we call ‘sleep disruption,’ in which you keep people from sleeping, there are measurable declines or impairments in cognitive performance.” Over time, not getting enough sleep “not only makes you feel horrible, but tends to put you at greater risk for chronic conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease,” which are, in turn, linked with a greater likelihood of cognitive impairment and dementia, Liu-Ambrose says.

Moreover, there are important tasks the brain can carry out only when we’re asleep, including consolidating the memories we’ve formed during the day. We also need to be asleep for the brain’s own waste-disposal system—discovered only a few years ago—to do its work. According to Liu-Ambrose, in sleep-deprivation studies, “researchers saw more toxin accumulation in the brain than after a normal night of sleep.”

Measures that can help you drift off at night and stay asleep include going to bed and getting up at the same time every day, ensuring you’re exposed to natural (or artificial full-spectrum) light early in the day, and eating meals on a regular schedule. On the other hand, Dr. Howard Chertkow, the chair of Baycrest’s Department of Cognitive Neurology and Innovation and a senior scientist at the Rotman institute, cautions against taking medications to induce sleep. “Sleeping pills, particularly if you take them every night, accumulate in your brain and will affect your memory,” he explains.

Flex your mental muscles.

Observational studies have hinted that speaking two languages has a protective effect on the brain. “There’s some work showing that people who will develop dementia but who are bilingual tend to get diagnosed with dementia later—as much as four years later,” Meltzer says. Bilingual brains are also better able to compensate for dementia-related damage.

Many people grow up with a second language, or at least learn it long before age 55, which has researchers like Meltzer wondering “whether there’s any kind of lifestyle intervention you can do to duplicate those [dementia-protective] gains.” So he and his colleagues “designed a study to look at the cognitive effects of studying Spanish for four months, 30 minutes a day, using an app,” Meltzer explains, “compared with the effects resulting from a more traditional brain-training app” and from no intervention at all. All participants took cognitive tests at the start of the study and again at the end. In both app-user groups, “people had pretty strong improvements associated with bilingual advantage,” Meltzer says. “So it does seem you can improve your executive function—your ability to handle conflicting information and multi-task.”

Learning to speak a second language is just one way to challenge your brain. Research suggests that taking up a new form of artistic expression, visiting art galleries or museums, attending concerts, and volunteering—among other cultural, social, and educational activities—also bolster brain health.

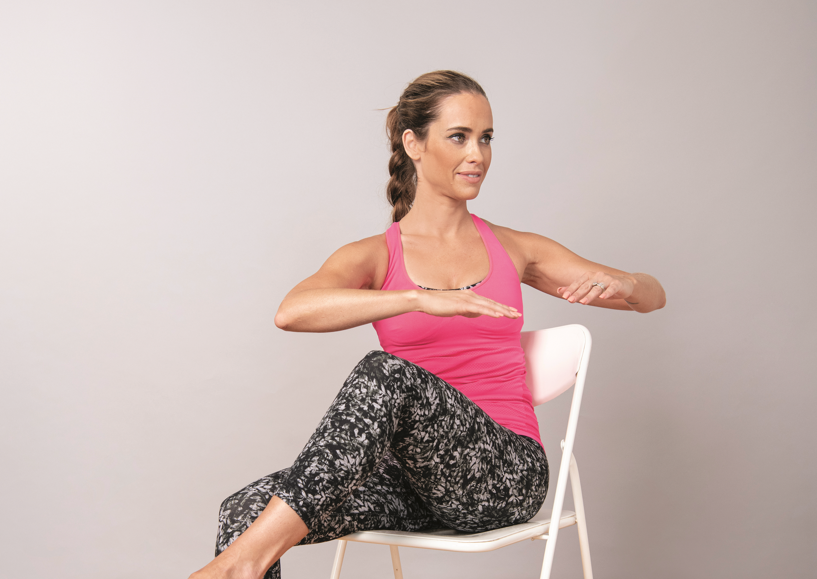

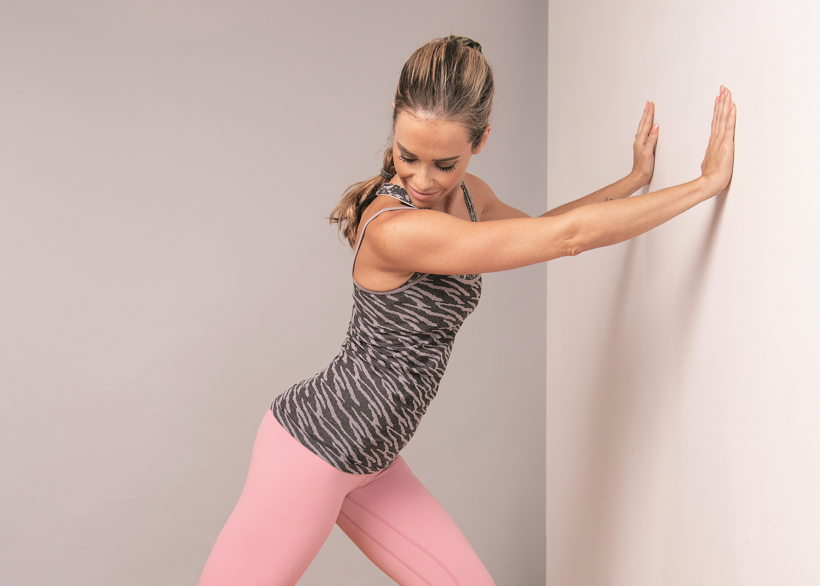

Exercise.

Of all the things you can do to rejuvenate your brain, according to a growing stack of evidence, regular physical activity confers the greatest benefits by a wide margin.

For one thing, exercise helps keep blood vessels healthy, including the arteries that supply blood to the brain. Some research has revealed that exercise also boosts levels of substances that promote the growth, maturation, and survival of new brain cells. Other studies have shown that when sedentary older adults participate in moderate-intensity aerobic activity three times a week for a year, the hippocampus (that part of the brain that plays key roles in memory and learning) increases in size by two per cent (by contrast, it typically starts shrinking by one to two per cent a year after age 55).

Several experimental studies led by Liu-Ambrose have found that both aerobic activity and strengthening or resistance exercise can improve performance on tests of different types of mental function. In trials comparing older adults who participated in exercise classes to those who either didn’t exercise or engaged in lower-intensity activities, “we’ve shown that adults who engaged in those forms of exercise improved in their cognitive ability,” Liu-Ambrose says, “whether they can remember things better or make decisions faster.”

And that’s not all. “When we scan their brains with neuroimaging, we can see increases, especially in critical areas that we know tend to be affected by both aging and disease. We also see the brain function changes, whereby the brain may be able to recruit additional areas to perform a task better,” Liu-Ambrose says.

Perhaps most exciting of all, in people who already have changes in the brain that predispose them to developing cognitive impairment or dementia, “we’ve shown that exercising can actually minimize or slow down the progression of the pre-existing disease,” Liu-Ambrose explains. This is, she says, “phenomenal,” because it’s something that, as yet, no medications have been able to do.

Other research indicates that short bouts of exercise, even when they’re of relatively low intensity, can cause a surge in executive control, “a cognitive process that supports our ability to make decisions on a day-to-day basis,” says Matthew Heath, a professor at the School of Kinesiology at Western University in London, ON. (Heath draws the following analogy: Imagine you’re sitting at a red light, waiting to drive straight ahead; but the moment you see the green “left-turn” traffic light, your foot automatically jerks towards the gas pedal. The ability to quash that reflex before you press the accelerator requires a high level of executive control.)

To test the effect of different levels of physical activity on executive control in older adults, researchers had healthy older adults “exercise at various intensities—moderate, heavy, and very heavy—for 20 minutes,” Heath says. “‘Moderate’ was considered the equivalent of walking the dog; ‘heavy,’ walking on a slight incline; and ‘very heavy,’ hiking up a hill.” Before and after each session, participants performed a task that tests for a high level of executive control. “Exercising for 20 minutes resulted in a significant improvement in executive function” regardless of pre-existing fitness level, Heath says.

In an earlier study involving adults with very preliminary-stage cognitive impairment, participants exercised four times a week for six months, undergoing assessments of executive function after the six months and again six months later. Even at the final evaluation, “participants still had a benefit to their executive function,” Health says.

In short, “by far the most effective lifestyle intervention to protect the brain from dementia is physical exercise,” Meltzer says. “It has a larger effect than anything we’re looking at in terms of things you do on your phone or computer. And exercise doesn’t have to be super-intense to be beneficial. Walking versus not walking makes a much bigger difference than walking versus running.”

Indeed, when it comes to maintaining your brain health, “the evidence is suggesting it’s the little things you do on a daily basis, even when it comes to exercise,” Liu-Ambrose says. “We’re not talking about extraordinary efforts; we’re talking about consistent behaviours. So start small and keep these little additions as part of your regular repertoire.”

Photo: iStock/monsityj.