For the celebrated Canadian conductor, life’s a symphony

By Peter Feniak

Photo: Bob Hatcher.

‘‘Great music can make you feel alive—bursting with energy, ready to attempt the impossible,” says Boris Brott, the great Canadian conductor.

In the YouTube video containing that statement, Brott is speaking to a conference of business leaders about music’s power to draw more from us. Fortune 500 companies engage him as a motivational speaker who shows how music matters to success-linked concepts such as creativity, innovation, and team-building. He supplies this audience with “tone bars” and mallets, divides them into sections, and leads them in a few bars of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” The result is indeed joy—and some new ways of thinking.

Among his many roles—conductor, musician, entrepreneur, multiple honouree, husband, family man—Brott prizes that of teacher. He learned to share his love of music from the late Leonard Bernstein, the brilliant composer and charismatic conductor of the New York Philharmonic. Brott has called him “a genius, a wonderful teacher.” Bernstein was a sensation in television’s early days, an energetic guide through the world of classical music, and at the age of 24, Brott was his assistant conductor.

A year later, Brott arrived in Hamilton, ON.

“People were already talking about him as the next great maestro,” says Graham Rockingham, the music editor of The Hamilton Spectator. “It was extraordinary that Hamilton was able to hire him. And he was so hip; he reached out and he made classical music hip. He took the orchestra onto the factory floor at Dofasco, into the steel mills. He was one of the first people to bring a rock band onstage.” To Rockingham, Brott has always been about outreach and education. “Boris believed that if you get them in, they keep coming back.”

In his 21 years as the artistic director and conductor of the Hamilton Philharmonic, Brott raised the orchestra’s professionalism, artistry, and audience to new levels. And then, in 1990, Brott says, “I was fired.”

He remained in Hamilton with his family, nurturing musical enterprises that enrich the city, flying out often to guest-conductor assignments. A Spectator poll in 2006 placed him among the top five “Greatest Hamiltonians.”

Being Musical

I met the maestro—now a hale and voluble 74—in his home office on a bright spring day. Home is a remarkable high-ceilinged three-storey Victorian mansion trimmed with burnished oak in Hamilton’s historic Durand District. He shares the building with the offices and staff of the National Academy Orchestra of Canada and the Brott Music Festival, busy organizations that he and his wife, Ardyth, founded. At first, the couple rented the second floor. They raised their three children there.

The maestro’s sizable office has two large desks, a meeting table, and plenty of technology. Rows of bookcases are crammed with music scores. The walls feature framed awards and photos of Brott with immediately recognizable friends such as Harry Belafonte, Ella Fitzgerald, and Princess Margaret. Dominating the room is a large oil portrait of a great symphony conductor/composer at the podium—Brott’s father, Alexander Brott.

Boris Brott was born in Montreal in 1944, the elder son of two brilliant classical musicians. (His brother, Denis, was born in 1950; a former cellist with the much-admired Orford String Quartet, he is currently a music teacher and is the founding director of the Montreal Chamber Music Festival.)

Early days were modest. “We lived for the first seven years of my life in one room in my grandparents’ fourth-floor walk-up on Maplewood Avenue,” Brott says. “In that room, my parents practised, my father wrote music…the McGill String Quartet rehearsed there from the time I was in a bassinet.” That celebrated quartet included Alexander Brott on first violin and Lotte Goetzel Brott, Boris’s mother and the group’s cellist and general manager. The quartet grew to become the McGill Chamber Orchestra, with Alexander Brott as the artistic director and conductor. Since 2005, Boris Brott has been returning to Montreal regularly as the same orchestra’s conductor and artistic director, proud to follow his father as the leader of what has been called “an ensemble of international standing.”

“I don’t have any real recollection of not playing the violin,” Brott says. “My parents told me that around the age of three, they stuck a 1/16 [size] violin under my chin that my father had bought in Czechoslovakia.” Brott learned quickly—he was invited to perform as a soloist with the Montreal Symphony when he was five years old. He played a Vivaldi concerto at a youth concert.

Eventually the family moved to a duplex in Montreal’s Notre-Dame-de-Grace district (NDG to English-speaking Montrealers). “My grandparents had the upper floor, we had the lower,” he recalls. “My parents were very busy musicians, so I was in the care of my grandparents a lot of the time.”

It wasn’t easy being musical, Brott recalls. At school (“Royal Vale, across the park from where we lived”), he was “different”:

“I felt that I was ostracized. Kids couldn’t understand that I couldn’t play contact sports because my mother and father were concerned about my hands. So I thought, Well, I’ll bring my violin to school and play it in Assembly so they can see what I’m doing. That was my biggest mistake,” Brott laughs, “because I got snowballed all the way home.”

Brott says he tried “to escape music.”

“I joined the hockey team. I played baseball and all the things with the other kids. But I was supremely untalented. I had two left feet! I was really bad. So I realized that music was what I was good at and there was no point in pursuing something where I was clearly not gifted.”

Music Power

In the years after the Second World War, Montreal—Canada’s sparkling big city—was an attractive destination for some illustrious members of the world’s classical music community. Brott’s parents knew them all. The visiting Russian conductor/composer Igor Markevitch took an interest in young Boris.

“He said, ‘I know you’re a violinist. How do you see your future?’ I said, ‘I find all this business of practising four or five hours a day really wearing. And I have no friends and I’m a people person, and I find this really difficult.’ He said, ‘Have you ever thought of being a conductor?’”

Markevitch, at the time the conductor of Mexico’s National Symphony Orchestra, ran a course for would-be conductors to study “form and analysis, composition, all those things.” Brott was invited to Mexico for the summer to study.

“Long story short, he found a job for my mother, running the course,” Brott says. “Then that led to my staying the entire next year at the Instituto Nacional de Belles Artes. I just took a year off school.”

Brott doesn’t like the word “prodigy” to describe his younger self, but his talent was evident. Back at home, the teenager guest-conducted a youth concert with the Montreal Symphony. He graduated from West Hill High School at 17, having attended part-time; the rest of his time during those days, he completed a degree in music at McGill University.

He continued to study conducting with the esteemed French conductor Pierre Monteux, who called Brott “one of the finest, most serious talents I have ever encountered among young conductors.” Brott was learning, he says today, a kind of “magic—each conductor brings a different sound from an orchestra.”

Brott’s first engagement, at 19, was conducting Britain’s Northern Sinfonia (in Newcastle), where his youthful energy proved winning. Shuttling between assignments, he was soon attached to the Toronto Symphony as assistant conductor, then, for four years, was principal conductor for the touring company of Britain’s Royal Ballet. His inspiring time with Leonard Bernstein also included work back in Canada, developing the music program at Lakehead University and the Lakehead (now Thunder Bay) Symphony. Then came an offer from Hamilton.

Brott smiles as he remembers his years as conductor and artistic director of the city’s Philharmonic Orchestra.

“Oh, it was a tremendous amount of joy, making music at a very, very high level. It began with this dream that I had when I came—not hiring individuals, but rather hiring already formed ensembles, quartets, and quintets. It started with a first-class international ensemble: the Czech String Quartet, who arrived in the middle of August with fur coats, expecting a country in which there were a lot of people in igloos.” (The orchestra’s brass section gave birth to the popular quintet Canadian Brass.)

Brott’s talent, energy, and innovations intrigued Hamiltonians. Graham Rockingham describes a poster from 1972 proclaiming: boris brott: music power.

“He’s wearing a double-breasted suit jacket with an Apache scarf, he has long sideburns, he’s looking very svelte, with longish hair. And he’s standing in the middle of an open-pit quarry, leaning on the front fender of what looks like a giant dump truck, surrounded by seven miniskirted models. To his right is a leather-jacketed Ardyth, whom he’d just met.”

Ardyth Webster—lawyer, children’s author, and daughter of the late Philharmonic mainstay Betty Webster—became essential to Brott’s life. Married for 41 years, they’ve raised their children and shared the journey of the orchestra together. “It’s a great partnership,” Rockingham says, “a great love affair.”

Brott’s tenure meant transformation for the Philharmonic.

“When I first came in 1969, the Hamilton Philharmonic was an amateur orchestra. And we built that orchestra to a full professional ensemble. We had a 40-week season. We were filling Hamilton Place for all our subscriptions. We had pops concerts. We had a variety of different musical silos—chamber music, contemporary concerts, family concerts, choral/orchestral concerts, opera. We sent the instrumental groups into the schools—strings, woodwinds, brass, percussion—then finally the whole orchestra. We had a series of ‘candlelight and wine concerts’ between Burlington and Hamilton. It was very much a thriving enterprise.”

And then, Brott says dispassionately, “It came to an end. Not of my own accord. The board had, or I had, a different vision for what this should be or could be.”

Maintaining a fine orchestra is a complex and costly business. The early organizations Brott knew in Montreal were different. “They had this board of directors of wealthy people; they didn’t really fundraise. At the end of the year, there was a deficit of X-thousand dollars and they had 12 people and they divided it by 12 and they all wrote cheques.” He slaps his hands in a “that’s done” gesture.

Today, fundraising is crucial, government grants must be won, audience-winning guest artists engaged, innovative programs devised. Orchestras, Brott says, are “not in the profit business but in what I like to call the ‘lack of loss’ business.” And, he adds, today’s orchestra musician “has to be entrepreneurial”—finding other performing outlets and teaching and session work to supplement what orchestras can pay. Ultimately, boards of directors make tough choices about what can or can’t be done. The Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra declared bankruptcy in 1996; revived, it is now under the baton of New Zealander Gemma New.

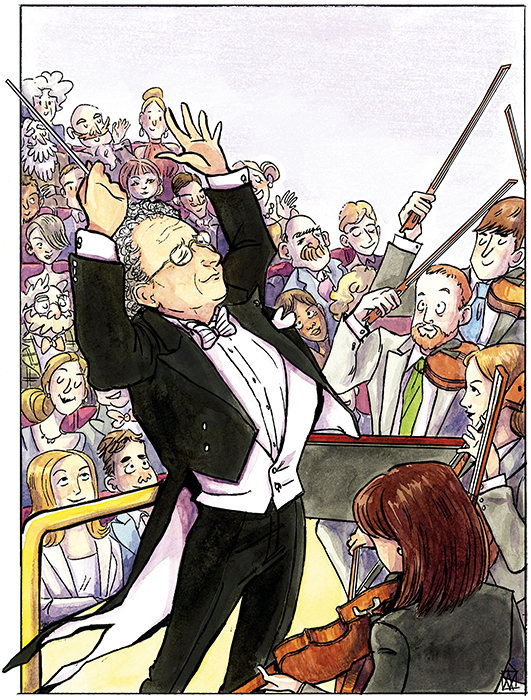

Cover image of the 2017 Brott Music Festival program.

Illustration: Agathe Veyrat.

The “Big Salad”

The Brott family was challenged as the 1990s began.

“I found myself here in this house, with three school-age children—the youngest, Benjamin, was just in school—wondering what I was going to do for the rest of my life.”

Ardyth chose law school and was called to the bar in 1995. Boris took the LSAT (Law School Admission Test) and began studies himself, but music drew him back.

In Hamilton, the Brotts nurtured two enterprises. The National Academy Orchestra of Canada, the first of these, auditions young musicians to apprentice with experienced working musicians in a program of study and performance. “This is our 30th anniversary,” Brott says proudly, “and we have graduated a phenomenal who’s who of over 1,500 musicians for whom we have found positions all over the world.”

The National Academy Orchestra performs in Hamilton and the surrounding region from June to late August in the Brott Music Festival, their second endeavour and Canada’s largest non-profit orchestral music festival, with innovative programs to “bring them in and keep them coming back.”

Brott’s entrepreneurial spirit has served him and his projects well. He remains an internationally admired conductor who has conducted, as is often said of him, “from Carnegie Hall to Covent Garden.”

He has led orchestras on four continents. He became the founding music director and conductor of the New West Symphony of Los Angeles (1995 to 2011). And in 2000, he realized a dream long held by his mentor, Leonard Bernstein, of conducting an orchestra at the Vatican in a performance of Bernstein’s daring—and controversial—“Mass.” (The composition is subtitled “A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players and Dancers.”) The huge audience included Pope John Paul II, and the program was televised worldwide. And Brott continues to record with fine artists—recently Mozart’s Concerto for Three Pianos with Britain’s Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, featuring Hamilton pianist Valerie Tryon.

His work across Canada over the years has included key roles in the development of symphonies in Thunder Bay, Regina, Kitchener-Waterloo, Winnipeg, and Nova Scotia. The portrait of Alexander Brott in his office shows the great conductor wearing his Order of Canada medal. An Officer of the Order, Boris Brott proudly wears the lapel pin of the Order on his vest. “Like father, like son,” he grins.

For this interview, he’s been generous with his time, offering a brief tour of the remarkable mansion, sharing stories from a life in music, and occasionally interacting with his busy, upbeat staff. The interview ends in front of a computer screen with a video showing a large audience of school children utterly engaged with an orchestra, singing along to a performance of Queen’s “We Are the Champions.” Brott’s face brightens with delight to see the young so affected by music. “Music grabs their attention,” he marvels.

Of his demanding schedule, his passions, his challenges and commitments, he says, “It’s a big salad,” adding, “I have always slept less than the eight hours you really need.” His days begin early, “usually around 5 a.m.—a good time to get some studying done, except, in Europe, it’s already daytime: they know they can reach me at that time.

“I like the challenge of it,” he says, “developing funding, developing audiences—basically proselytizing for great music. I enjoy life.”