Most of us are experiencing some level of stress these days. Here are some ideas for dealing with it effectively

By Wendy Haaf

The daily grind can be stressful, but if you’ve already retired, you know that stress doesn’t magically disappear when you blow out the candles at your retirement party.

Those over 55 may even be more prone to stress than are younger people: according to a report from the Calgary Foundation, 90 per cent of seniors in Calgary are subjected to daily stress, compared with just 69 per cent of millennials. Older people can find themselves under intense prolonged stress (caused, for example, by major life transitions such as downsizing) at a time when their brains and bodies may be less able than they were, due to aging and medical conditions, to shake off the negative consequences.

However, there are a number of simple everyday strategies that can dial down stress and improve our capacity to withstand it. What’s more, research has shown that even when our defences give way and we begin to suffer the effects of stress, there are techniques that can bolster our mental well-being.

Good Stress, Bad Stress

Not all stress is necessarily bad.

“Stress can be a gift in moderate amounts. It gets us interested in and excited about important goals and relationships, and can be protective in threatening situations,” says Nasreen Khatri, a clinical psychologist, gerontologist, and researcher with the Rotman Research Institute at Baycrest Health Sciences in Toronto. For instance, it can motivate us to take positive steps such as setting firm boundaries with people who drain us emotionally or take advantage of us. In ideal circumstances, once we take action, the stress ebbs and our bodies return to a more relaxed state.

“The problem is that in those on the road to having mental health problems, the stress level doesn’t come back down quickly or efficiently enough to maintain good health,” Khatri says. And of course, sometimes the stress is ongoing due to long-term challenges such as having to quarantine, providing care for a spouse or family member, learning to manage a new health condition, and adapting to a major life change.

“Chronic exposure to stress can really affect older adults, who may be less resilient simply because we have more limited reserves as we get older, but also because stress can exacerbate pre-existing mental or physical health conditions,” says Elena Ballantyne, a clinical neuropsychologist at St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton (ON).

That can play havoc with our emotions, as well as with our bodies and brains. “Emotionally, we may feel exhausted, anxious, down, irritable, or weepy and have difficulty relaxing or winding down, even when given the chance to do so,” Khatri explains.

Some of the physical effects of stress, “depending on how severe or chronic it is, include headaches, muscle tension, heart palpitations, indigestion, unexplained aches and pains, and sleep difficulties,” Ballantyne says. “Stress can also weaken the immune system and cause some medical issues, such as increased blood pressure. Stress is associated with an increased risk for cerebrovascular and cardiovascular issues [such as stroke and heart attack] and diabetes.”

The potential fallout doesn’t end there. “When someone is chronically stressed, the elevation of stress hormones can affect the ability to think clearly, to pay attention, and to remember information,” Ballantyne explains.

Under chronic stress, “mentally, we have more difficulty meeting the challenges of daily life,” Khatri says. “We develop problems with motivation, staying organized, planning, and problem-solving.” This can all hamper our capacity to stick to the habits that help us stay physically and mentally healthy. For example, “When we’re really stressed out, we may be less likely to manage pre-existing health conditions and take medications as prescribed,” she says. Persistent unremitting stress can increase the chance of developing mental health problems, too. “Chronic stress, caregiving burnout, and chronic anxiety can all lead to depression, which, in turn, affects attention and memory,” Ballantyne says. Moreover, depression itself has the potential to sabotage long-term brain health.

“We know that those with a history of untreated depression in mid-life and beyond are twice as likely to develop dementia later on, compared with people who don’t share that history,” Khatri explains. The mental and emotional toll of chronic stress, she says, “puts us at a greater risk for everything from accidents and lapses of judgment to relationship problems.”

Some of these thinking, memory, and mood issues probably occur because stress can physically reshape the brain in detrimental ways.

“When these stress hormones get released chronically, they can prune the branches of neurons and prevent the creation of new neurons, particularly in areas related to memory,” Ballantyne says.

If all this has you stressed out, take a deep breath and let’s find out what you can do to shore up your defences and cushion the impact of stress.

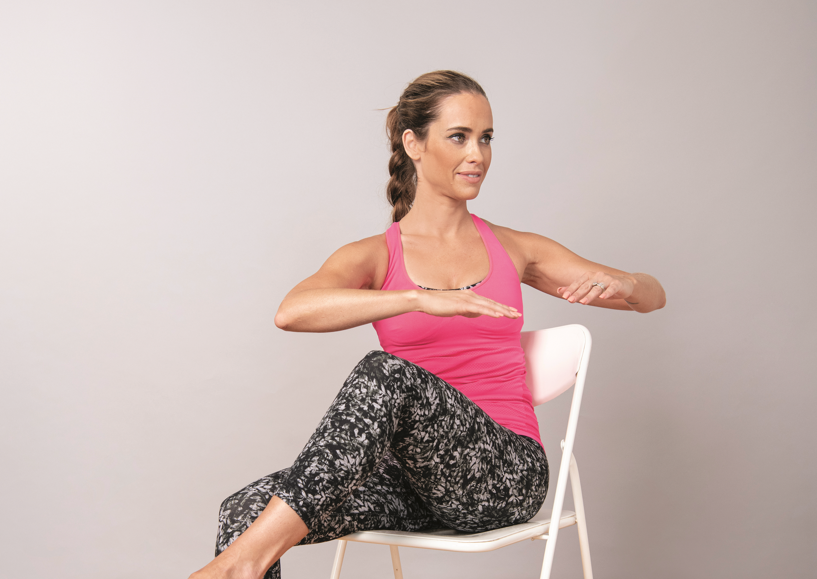

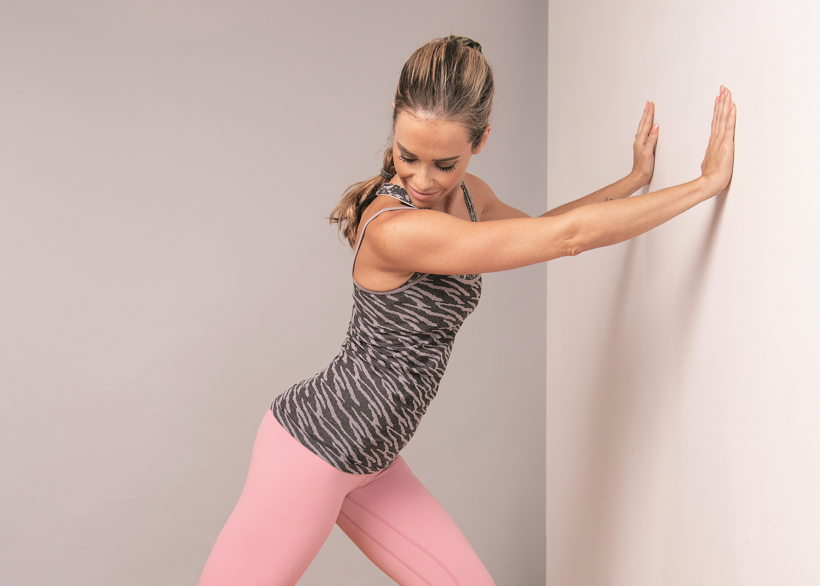

1 Get physical.

Even if you do nothing else to combat stress, build physical activity into your weekly routine.

“Exercise is quite effective for reducing stress,” Ballantyne says. But just as important, “it reverses some of the impact of stress on the brain itself. It makes brain cells healthier again and can lead to the creation of new neurons and to getting those branches back onto the neurons, particularly in areas of the brain related to attention and memory,” she adds.

While a minimum of 150 minutes a week of moderate to vigorous aerobic activity is ideal, any amount that you can manage is better than none. “It doesn’t take a ton of exercise,” Ballantyne says. “Spurts of 10 or 15 minutes here and there can really make a difference, particularly in combination with other strategies.”

2 Decaffeinate.

“One thing that shows up again and again in my practice is that people really underestimate the effects of caffeine,” says Kate Partridge, a clinical psychologist in London, ON.

Because sensitivity to caffeine’s effects varies from one person to another, sometimes even a small amount of caffeine can help fuel a vicious cycle of worsening mental and emotional tension. For one thing, even when consumed early in the day, it can lead to disrupted sleep, which has been shown to contribute to psychological stress and strain. “No matter what your general tolerance level is, it goes down when you’re stressed, because your body is filled with stress hormones; caffeine is just another stressor,” Partridge says. To find out if that seemingly soothing cup could be having the opposite effect, she suggests the following experiment: “Go on a caffeine holiday for four weeks, after a gradual cutback.”

3 Recharge.

Prolonged attention to one task can lead to stress and exhaustion. “Take breaks throughout the day and give yourself permission to pause and just be,” Partridge advises.

Turn off your phone and take a brief stroll, or find a quiet spot and sit, focusing only on the sights, sounds, and smells around you. And since some research suggests that spending time in a park or natural setting is particularly calming, causing levels of stress hormones to plummet after just 15 minutes, try spending some of that regular downtime in the great outdoors.

If you have a daytime job, “actually take your lunch break, don’t stay late every night, and take off your weekends and holidays,” Partridge urges. “And give yourself enough sleep—people who think they’re getting more done by sleeping only six hours a night are really damaging themselves.”

4 Pursue a passion.

Enjoy photography? Always yearned to learn how to paint or play guitar? Dive in. There’s evidence that hobbies, ranging from reading and knitting to playing an instrument, can cut stress levels and leave us feeling more relaxed and rejuvenated. And such activities have been linked with a lower likelihood of developing dementia later in life.

5 Stay connected.

Often when we’re feeling tense and overwhelmed, we abandon or put off “frivolous” activities such as meeting a friend for coffee or lunch, attending a book club, and going to other group meetings, but that’s precisely when it’s most important to make time for such pursuits. Naturally, social distancing has been making that a challenge, but when things are normal again (or at least more normal), we’ll need as much human contact as we can get.

“Connecting with friends and family, doing group activities, joining a seniors’ centre or a club—interacting with other people—is very healthy, not only for our mental health and for reducing stress, but for our brain health, as well,” Ballantyne says.

If you’re so inclined, finding a way to help others by volunteering for a non-profit or charity, or even bringing the occasional meal to a neighbour who has difficulty getting out of the house, may be especially helpful for buffering stress. A number of studies have found that volunteers report lower stress levels than non-volunteers and even feel less rushed; paradoxically, giving others your time seems to make you feel as if you have more of it to spare. Volunteering can also provide a sense of contributing to something bigger than yourself or give you a feeling of inner purpose.

“We see that when people find meaning in their lives and find a new purpose, even in the face of adversity and after significant loss, their stress levels go down,” Ballantyne says. “It’s not about solving all your problems.”

6 Eat a healthy diet.

While some of us might choose to reach for a glass of wine or comfort foods rich in fat and sugar when we’re feeling anxious and stressed, there’s evidence that, like caffeine, alcohol and sweets can exacerbate stress. On the other hand, vegetables, fruits, nuts, and fish seem to help quell it, as does eating at regular times and not skipping meals. And eating plans that are rich in the latter group of foods are linked with a lower incidence of a host of health problems, including heart disease and dementia.

7 Enlist practical help.

If you’re struggling to keep up with everyday tasks such as housework, home maintenance, and cleaning due to other commitments, such as caring for a parent or partner, look for ways you might be able to hand some of those duties off to someone else.

“For example, see if your local grocery store can deliver groceries or your pharmacy can deliver your prescriptions,” Ballantyne suggests. Perhaps you could consider hiring a cleaning service or finding respite care so you can slip away for a few hours of R and R. (Your physician, your community care access centre, and organizations such as the Alzheimer Society of Canada are often good sources of information about the kinds of services and supports available in your community.) Research has shown that shelling out for time-saving assistance (such as paying a neighbourhood teen to mow the lawn) makes people happier than spending money on material goods, and that “when we can delegate some of these tasks to other people, our mental health improves and our stress levels go down,” Ballantyne says.

8 Practise a technique.

From guided imagery and various forms of meditation to tai chi and yoga, a number of relaxation practices are backed by scientific evidence as helping to reduce stress.

“Choose something you’re genuinely interested in and motivated to try,” Ballantyne advises. “Everything isn’t for everybody.”

If possible, take an introductory class led by a knowledgeable instructor rather than simply downloading an app or buying a DVD to test a new-to-you technique on your own: just as you can derive no benefit from and even injure yourself by, say, doing a physiotherapy exercise incorrectly, you may not get the best results without some in-person teaching.

Many of these practices incorporate deep breathing, which in itself can help dial down stress. And while you might think that you know how to do it, chances are that you’re mistaken. “Most people, if you ask them to deep breathe, take a big, big chest breath,” Partridge explains. “What’s really helpful is learning how to let your body go back to breathing the way it did when you were born, which is abdominally.” If you watch a sleeping newborn, you can see her belly puff up when she inhales—that’s what you’re aiming for. With repeated practise—for example, in a mindfulness meditation class—you can gradually train your body to breathe that way all the time, without conscious effort. “That’s how you really lower the background stress level of the body,” Partridge says, “because abdominal breathing promotes the state of ‘calmed-down-ness.’ When you’re chest breathing, you’re creating the physiological conditions to increase stress on the body.”

Regardless of the type of relaxation technique you opt for, the daily repetition that’s required to permanently alter your breathing pattern is key.

“You need to select some strategies that you find engaging and helpful and do them on a regular basis, even when you’re feeling well,” Ballantyne says. “By getting your mind and body used to the practise, when you do face a stressful period, you’ll be more likely to induce a relaxation response, because your body knows what to do.”

9 Talk with your doc.

If you’ve been feeling stressed, sad, or anxious most of the time for several weeks or your distress is interfering with two or more areas of your life (for example, relationships and your ability to carry out day-to-day activities), Ballantyne advises checking in with your family physician.

“A good thing to do before you do anything else is to get a medical assessment of your physical health,” she says, “because stress can cause medical issues that you may not be aware of, such as hypertension. You need to make sure that you’re catching all of this and getting any treatment you need to manage those conditions.”

10 Get extra help.

“If stress is a major problem and you have access to private insurance, seeing a mental health professional to come up with individualized strategies is certainly very important,” Ballantyne says. If you don’t have private insurance, your doctor, area health unit, or local hospital may be able to suggest services in your community that are publicly funded or low-cost.

If your stress stems from adverse circumstances over which you have little control, “a type of therapy called ‘acceptance and commitment therapy’ can be particularly useful,” Ballantyne says. This intervention, she says, helps guide someone through such questions as: “How do I find meaning in my life?” “Given the limitations I’m facing, what can I do?” “Who and what is important to me?” and “How do I make choices that are going to get me closer to this meaningful life, even if I have health problems or I’ve lost a partner?”

Retraining your brain to recognize, challenge, and change negative thinking patterns—a model of treatment called “cognitive behavioural therapy”—has also been proven effective for managing stress and for treating anxiety and depression.

Whether or not you end up needing a bit of extra help dealing with your stress, however, one thing is clear: taking care of your mental health with strategies such as accepting assistance from others and making time for hobbies is no more selfish than taking care of your physical health by eating well and exercising. In fact, both are equally important—and interconnected. “By keeping your body healthy,” Ballantyne says, “you’re keeping your brain healthy, and vice versa.”

Photo: iStock/Image Source.