Four experts weigh in on how to keep your kidneys in top shape

By Wendy Haaf

Roughly two million Canadians are living with some form of kidney disease, and while only a relatively small minority will see their condition progress to the point of requiring life-extending dialysis or a kidney transplant, the number of people over 55 in that situation has increased dramatically in the last decade or so. According to a report this year from the Canadian Institute for Health Information, the number of Canadians aged 65 or older with end-stage kidney disease surged 66 per cent between 2003 and 2013; cases among those aged 45 to 64 climbed 42 per cent.

While part of that increase is undoubtedly due to the fact that we’re living longer and are therefore more likely to develop one of the conditions that can lead to kidney failure—the top two culprits being diabetes and high blood pressure—it’s still a troubling trend, given that dialysis (the most widely used treatment) is linked with a significant drop in both quality and duration of life. Only 41 per cent of seniors live more than five years on dialysis: for one thing, chronic kidney disease is a risk factor for heart disease and vice versa.

In addition to living with strict dietary limitations and spending several hours three times a week tethered to a machine, people on dialysis can experience symptoms that include bone-deep exhaustion and are often unable to stray far from the location where they receive treatment.

“Dialysis alters your life in so many ways—not only yours, but your family’s,” says Neil Thompson, president of the Canadian Association of Nephrology Social Workers. For instance, he notes, plans to travel during retirement are often dashed.

On the other hand, it’s often possible either to reduce the likelihood of developing chronic kidney disease (CKD) or to slow its progress once it’s under way. We asked four experts for their advice on how to take care of your kidneys. Here’s what they had to say.

EAT A HEALTHY DIET

“It’s important to eat right,” says Dr. Patrick Parfrey, a nephrologist and John Lewis Paton distinguished professor of medicine at Memorial University of Newfoundland in St. John’s.

An eating plan rich in vegetables, fruit, whole grains, legumes, nuts, fish, and healthy oils (such as olive oil), with limited amounts of salt, red meat, saturated fats (found in meat and full-fat dairy), and sweets, can reduce your chances of developing risk factors for CKD—Type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease. (High blood pressure and high blood sugar can both damage and scar the tiny filters inside the kidney, while obesity increases the risk for both of these conditions on top of increasing the kidneys’ workload.) In one study that tracked 900 people for almost seven years, participants who adhered most closely to such a Mediterranean-style diet had a 50 per cent lower incidence of kidney disease than did those whose eating habits veered most from this pattern.

For instance, the potassium abundant in vegetables and fruit helps keep blood pressure down, as does limiting sodium to 2,400 mg/day or less. (Some experts believe that too much salt in itself may be harmful to kidneys, forcing the organs to work harder to rid the body of the excess, and some evidence suggests a high-sodium diet may accelerate kidney disease.) “A typical Canadian will be taking in 3,500 to 4,000 mg of sodium per day,” says Dr. Kevin Burns, director of kidney research at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and a professor of nephrology at the University of Ottawa. Since roughly 80 per cent of this total comes from packaged and restaurant foods (which are often also loaded with unhealthy fats), simply cooking from scratch and reading labels carefully can go a long way towards reducing sodium intake. “Most people, once they adjust, find it’s not that difficult to achieve lower dietary sodium levels,” Burns says.

It’s also worth paying attention to what you’re drinking. Not only is sugary pop linked with an increased risk of developing Type 2 diabetes independent of its influence on body weight, diet, or otherwise, “most soda is pretty rich in sodium,” explains Dr. William Clark, director of the apheresis program at London Health Sciences Centre and a professor of medicine at Western University’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry in London, ON.

AVOID TOBACCO

In addition to upping diabetes risk by 30 to 40 per cent, smoking has a detrimental effect on blood pressure and blood vessel health, which can in turn affect the kidneys.

“Smoking also seems to make kidney disease worse,” Burns says. In one study that followed more than 64,000 Norwegian adults (124 of whom ultimately had end-stage kidney disease), current smokers had a four-times-higher incidence of kidney failure than did never-smokers.

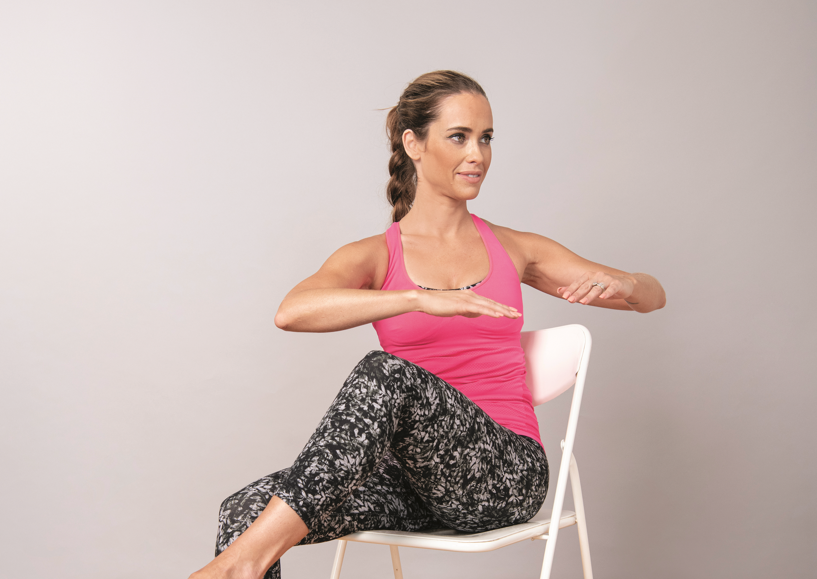

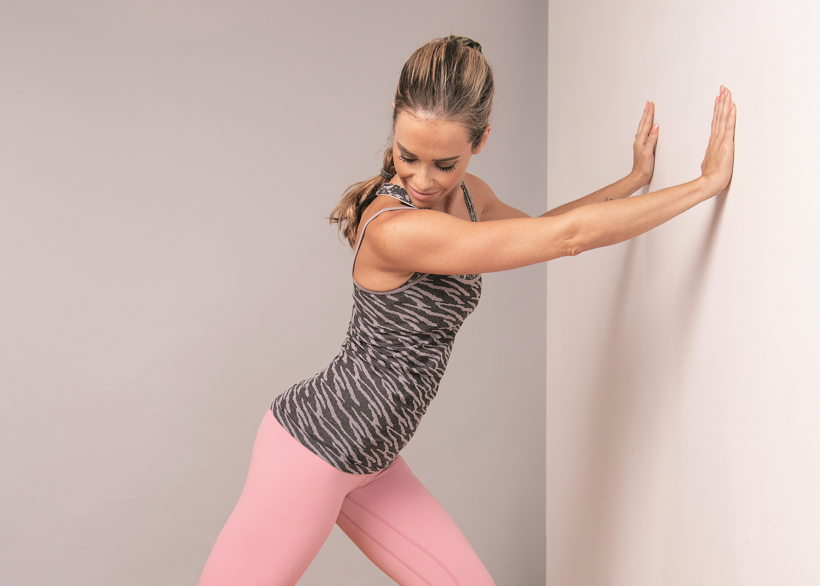

EXERCISE REGULARLY

In addition to helping to control blood pressure by keeping blood vessels flexible and healthy, regular physical activity reduces the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes in the first place and reins in blood sugar levels once you already have the condition. There’s even some preliminary evidence that exercise may slow the decline of kidney function once you have CKD.

“Try to find 30 minutes in your day for cardiovascular exercise,” advises Dr. Allan Grill, a Markham, ON, family physician and the Provincial Primary Care Lead for the Ontario Renal Network. “By that, I mean getting your heart rate up—a light jog, treadmill, bicycle ride, that sort of thing.”

MAINTAIN A HEALTHY WEIGHT

While it’s easier said than done, keeping off extra weight not only reduces the odds of developing diabetes and high blood pressure (the two leading causes of kidney disease) but also prevents extra wear and tear on the organs. After all, while a 250-pound person’s body will produce more toxins and chemical by-products that must be removed from the blood than will that of someone 100 pounds lighter, the kidneys of each contain virtually the same number of filters (about one million per kidney, for the record). In addition, obesity increases the odds of having higher levels of inflammation-causing compounds in the blood, which may contribute to blood vessel damage throughout the body, including the kidneys. (Once someone has CKD, obesity is also linked with a speedier decline in kidney function.) Your primary care provider, whether a family doctor or a nurse practitioner, can help you determine whether your body-weight-to-height ratio could be placing you at an increased risk for Type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

DRINK MODERATELY IF AT ALL

“Generally speaking, adult males can have two drinks a day and adult females can have one or one-and-a-half without affecting blood pressure and without affecting kidney function,” Burns says. However, alcohol contains empty calories and may whet the appetite, so it may be worth dropping if you’re having trouble keeping your weight down.

ADDRESS KIDNEY STONE RISKS

“There’s recent research out of Canada that’s indicated that people who have kidney stones are at a higher risk of developing chronic kidney disease,” Burns says. “It may be because the stones, as they pass through the kidneys, cause scarring.”

A previous episode of kidney stones increases your risk of having another one in future, but there are strategies that can reduce the odds of a recurrence.

“A low-salt diet and drinking at least eight to 10 glasses of water per day will reduce your incidence of kidney stones,” Clark says. He and his colleagues are currently conducting a randomized trial to determine whether this amount of fluid intake can also retard the progression of CKD. “It may also be useful for preventing kidney disease itself,” Burns says. “By drinking a lot of water, you end up blocking hormones that can damage the kidneys.”

Research has linked abstaining from soda with a lower rate of kidney stone recurrence. The problematic ingredients in soda seem to be the fructose in non-diet varieties and the phosphoric acid used in non-citrus-flavoured pop.

And at least one study suggests that exercise may reduce the odds for a repeat bout of stones.

GET PERIODIC HEALTH CHECKS

“Sometimes people think, I don’t have to go for regular checkups because I feel fine,” Grill says. “But with conditions such as high blood pressure and chronic kidney disease, you may not have symptoms until it’s too late.” (Symptoms include fatigue and weakness, nausea and vomiting, swelling of the feet and ankles, and persistent itching.)

You should talk to your doctor about how often to go in for a periodic health exam. “You want to make sure that your blood pressure gets checked regularly and that your cardiovascular risk factors are addressed,” Grill says. “So have you been checked for diabetes? Has your cholesterol been checked? The reason that’s so important is that there’s a strong link between chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease.”

For some, that periodic health check should include two tests that help measure kidney function: a blood test called the estimated glomerular filtration rate (EGFR) and a urine test known as the albumin-to-creatinine ratio. (These tests are used both to diagnose and monitor CKD.) Who should have these tests?

“Certain medications, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which are very common painkillers, can be toxic to the kidneys,” Burns says. (Examples include ibuprofen and naproxen.) While these medications aren’t a common cause of kidney failure, the damage they can cause may be reversible if caught early, “so people with arthritis or other pain conditions who have to take these medicines regularly should probably have their kidney function checked,” Burns says.

According to the Ontario Renal Network and the Canadian Society of Nephrology, the same goes for people aged 60 to 75 who have one or more of the following risk factors for CKD: diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, cardiovascular disease (including a history of heart attack, stroke, and/or peripheral vascular disease), certain autoimmune diseases (such as lupus), and a family history of end-stage renal failure.

“Early detection of chronic kidney disease will increase the likelihood that someone’s kidney function can be preserved,” Grill says.

If you do turn out to have early stage kidney disease—CKD is divided into five stages, with one and two being early and five being end-stage, when the only treatment options are dialysis or transplant—you’ll need to have your kidney function rechecked periodically.

“When someone is diagnosed, you monitor them a bit more closely until you’ve established that they’re stable,” Grill explains. Most cases of CKD—about 90 per cent, he estimates—can be managed by primary care providers. However, if the results of the two tests start to fall within more severe ranges, “then these patients need to be seen by a nephrologist for specialized treatment and consultation.” That’s also true of people who have CKD that can’t be explained by known risk factors and those who have relatively rare conditions (such as lupus) that are linked with increased CKD risk.

CONTROL YOUR RISK FACTORS

If you have hypertension, diabetes, or high cholesterol, taking steps to keep these conditions controlled is critical, particularly if you already have early-stage CKD.

“There’s little doubt that high blood pressure leads to progression of kidney disease,” says Memorial University’s Dr. Parfrey. “Probably the single most important thing is to control blood pressure.” (Usually, a reading of 130/80 mmHg or lower is the goal.)

When diet and exercise alone aren’t enough to do the trick, antihypertensive medications are the next step. If you already have compromised kidney function, the first choice will be a drug belonging to one of two different classes: “Drugs that we call ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs] have been demonstrated to slow the progression of kidney disease,” Parfrey says. According to Burns, “These drugs protect the kidneys by preserving those filters—they actually keep them healthy-looking,” by lowering blood pressure inside the kidney itself. “That’s a big advance in kidney treatment in the past 30 years.” (Your physician may also prescribe one of these medications if you have diabetes or protein in your urine, even if you have normal blood pressure.)

Similarly, if you have diabetes, Parfrey says, “it’s important to control it because it’s lack of blood sugar control that causes the complications of diabetes, including kidney failure.”

According to London Health Sciences Centre’s Dr. Clark, “The reality is that about 20 per cent of those with diabetes will end up on dialysis, so it’s a significant risk, which is, to a large extent, avoidable for the majority—if they stick to a diabetic diet, lose weight, increase physical activity, and make sure their blood pressure is controlled using either an ACE inhibitor or ARB as the agent of choice.” (And since CKD itself raises cardiovascular risk even more than does a blood fat abnormality such as high cholesterol, doing these things pays double dividends: reducing your risk for heart attack and stroke, as well as for kidney disease.)

“I would say that close to half of those with diabetes I see who have kidney failure have never been on a diabetic diet,” Clark says, explaining that they mistakenly believe that this kind of diet simply involves cutting out sugar. (In fact, two key aspects are measuring the carbohydrates in each meal and snack, since the body converts these into sugar, and watching protein intake, since too much can raise blood glucose levels.) “Have they seen a dietitian? No. And that’s really unfortunate, because it’s an important part of prevention.”

TREAT MEDICATIONS WITH CARE

If you are diagnosed with some degree of kidney disease, you need to take precautions before taking any medications and supplements, both prescription and otherwise.

“Every time you are prescribed a medication, you should ask, ‘Is this going to affect my chronic kidney disease?’” Grill stresses. (While your family doctor will undoubtedly be aware of your CKD, other care providers, such as ER physicians or other specialists, may not be.)

Check with your primary care provider or pharmacist before taking any prescription or over-the-counter product: there are many medications and supplements that you may need to avoid either altogether or when you’re ill (for instance, if you’re dehydrated due to a severe stomach bug), or that will need to have an adjustment in the dose, depending on your level of kidney disease. Examples include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory painkillers such as naproxen and ibuprofen, certain heartburn and stomach-upset preparations, and some antihistamines, cold medications, and laxatives.

If you follow this advice, chances are good you’ll never need dialysis or a kidney transplant, even if you develop early stage kidney disease. Says Grill, “If you monitor patients and they maintain a healthy lifestyle and control such vascular risk factors as cholesterol, blood pressure, and blood sugar, the majority likely won’t progress to end-stage renal disease.”

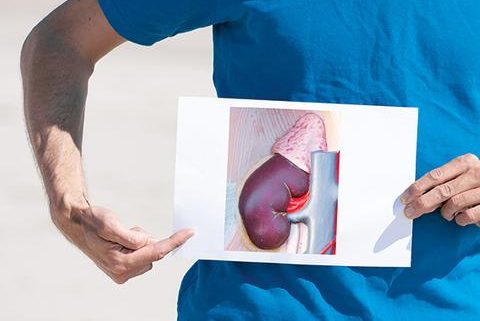

WHAT DO KIDNEYS DO?

Every hour, all of the blood in your body circulates through your kidneys, which each contain roughly a million tiny filters that remove toxins from the blood. (There’s a lot of extra capacity built into the system: you can live a perfectly normal life with only one kidney.) But that’s not all these hard-working organs do, according to Dr. Kevin Burns, director of kidney research at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and a professor of nephrology at the University of Ottawa. The kidneys also:

– control calcium metabolism and bone health,

– produce a hormone necessary to make red blood cells, and

– regulate the electrolytes in the body.

Consequently, compromised kidney function can lead to anemia, water retention (which in turn can cause swelling, high blood pressure, and, if severe enough, a fluid buildup in the lungs), and, later in the progress of kidney disease, high levels of potassium in the blood. This latter problem can be particularly dangerous. “It can cause muscle weakness and sudden cardiac arrest, which is why we sometimes have to do dialysis very urgently to remove it,” Burns explains.

ECONOMIC IMPACT OF KIDNEY DISEASE

“Even though Canada is a wonderful place to live,” says Shirley Pulkkinen, a renal social worker with the Algoma Regional Renal Program at the Sault Area Hospital in Sault Ste. Marie, ON, “for people who need dialysis, the social security net that’s supposed to be there has a lot of holes in it.”

For instance, while dialysis is covered by provincial health plans, patients must pay transportation costs to the dialysis clinic out-of-pocket—no small matter if you’re on a limited income and live a long distance from the nearest centre. Then there’s the time commitment—usually four hours per visit, three times a week, plus travel—which, if you’re employed, eats into work-time and may reduce your income.

Thus kidney disease disproportionately affects people living in rural areas and small communities, as well as those who are already at an economic disadvantage, says Neil Thompson, president of the Canadian Association of Nephrology Social Workers (CANSW). Because dialysis clinics are concentrated in larger centres, people who live in rural areas or small communities, he says, “are often told they have to relocate.” Even if that’s economically feasible—which it isn’t for many—some people opt to go without treatment (which results in death) rather than leaving friends and family.

And First Nations Canadians and women, who are already more likely to be living on a lower-than-average income, are at a higher risk of needing dialysis: the former because rates of both Type 2 diabetes—a risk factor for chronic kidney disease (CKD)—and a condition called glomerular kidney disease are higher among aboriginal Canadians than among the general population, and women simply because they tend to live longer than men.

“The lowest income earners are 50 per cent less likely to see a specialist when needed,” Pulkkinen says. “They may think, How do I get early treatments and the guidance I need to keep my kidney disease controlled? By the time I get to a doctor, it may be way too late.” People who live on a low income and don’t have drug coverage may also not be able to afford the medications they need to prevent or control chronic kidney disease. And while there’s a disability tax credit people with CKD can claim on their income taxes, Pulkkinen says, “if you don’t get enough income to pay income taxes, that tax credit doesn’t mean much.”

To get a clearer picture of the financial burden dialysis places on patients and their families, CANSW is undertaking a national survey. “As we approach municipal, provincial, and federal governments for changes—which we have done in conjunction with The Kidney Foundation of Canada—we need to be able to back up our statements with hard data,” Thompson says.