Exercise helps to keep your knees in shape—and helps improve mobility even if you have osteoarthritis

By Wendy Haaf

If you think you’ve beaten the odds—up to one in four—of developing osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee because you’ve managed to pass the half-century mark without experiencing ongoing or recurrent pain or stiffness (or both) in that joint, you could be mistaken.

While symptoms of the condition can appear between the ages of 35 and 50, knee OA is most common among people over 60, and for reasons we’ll go on to explain, those affected may be unaware of the fact for some time. That said, there are steps you can take to maximize your mobility and protect the health of your knees, even once the disease process (which erodes the bone-cushioning cartilage in the joint) is under way. Here’s what you need to know.

Why wouldn’t someone be aware that he or she may have knee OA?

“One sign of arthritis is that people lose a bit of the range of motion in the joint,” explains Mark Jesney, a physiotherapist at the University of Calgary Sport Medicine Centre, but unless you know what to watch for, “you may not notice it occurring.” One way of testing this is to lie on your back with your knees bent and slide your feet towards your body: if you can touch your heel to your bottom, you have full range of motion in your knee.

Those in the early stages of knee OA may also unconsciously change the way they move to avoid or minimize discomfort—for example, pushing up with their arms or using momentum when getting up from a sitting position. Jesney says he sees this type of scenario fairly often in those with a prior knee injury, which itself is a risk factor for knee OA.

“They don’t think too much of it, but you can tell that they compensate greatly; for instance, someone might stand up out of a chair every single time leading with one leg, while the other one is not really involved,” he says. The result? The muscles supporting the affected knee become weaker, increasing pressure on that joint.

So how do you know if you have a problem? “If you’re afraid of falling, or if you can’t get up off the floor from a kneeling position without using your arms, that’s a pretty good indicator you’re not where you should be,” says Isabel Aldrich-Witt, a physiotherapist at the University of Alberta’s Glen Sather Sports Medicine Clinic in Edmonton.

If I don’t have any of these issues, what can I do to keep my knees healthy?

First of all, if you can, try to keep your weight in the healthy range: excess body fat not only exerts extra stress on your knees, it produces compounds that contribute to the erosion of cartilage. You should also pay attention to what you eat: red meat and heavily processed foods loaded with sugar, simple starches, and unhealthy fats seem to promote the release of the inflammatory substances that are seen in knee OA, while a diet abundant in vegetables, fruit, fish, whole grains, and heart-healthy fats appears to have the opposite effect.

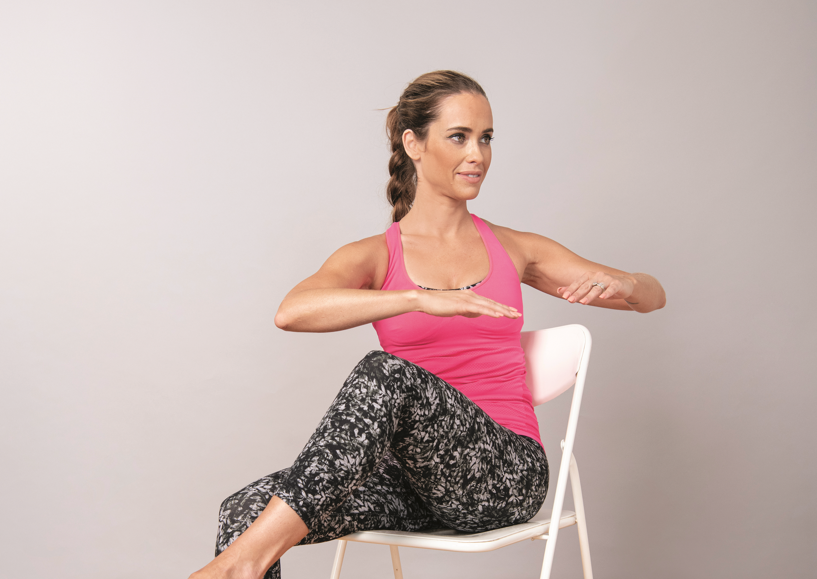

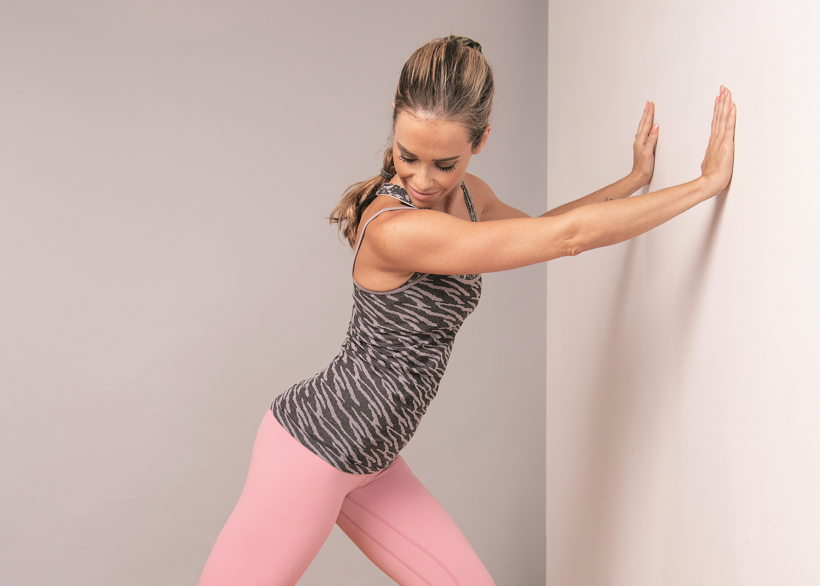

Weight-bearing activities such as walking and climbing stairs help keep cartilage thick and strong by stimulating healthy turnover of the tissue, as can cycling. However, two other types of exercise are also important for protecting your knees: those that strengthen the muscles around the joint (resistance) and those that foster proper range of motion (typically flexibility or stretching, unless you have hypermobile joints).

Resistance exercises involve working against a force of some kind, ranging from water or your own body weight to TheraBands or weights. While cycling doesn’t put your knees through a full range of motion, it’s a good start, and tai chi, yoga, and Pilates are examples of activities that incorporate stretching movements. (A bonus: the latter three also shore up the strength of your corsetlike core muscles, which helps minimize stress on your knees.) Just make sure you choose activities or sports you actually enjoy—if something feels like a chore, you’re less likely to do it regularly.

Don’t love exercise and think that walking and working around the house will be sufficient to protect your knees? “It may not be enough,” Aldrich-Witt says. That’s because some people unknowingly adapt the way they move so that their muscles and cartilage aren’t receiving the type or amount of stimulation they need to stay strong. (Read on for a suggestion on what to do if you’re concerned about this.)

How do I figure out what kinds of strengthening and flexibility exercises I need to be doing?

Since every person is different, there’s unfortunately no one-size-fits-all answer. Consequently, an assessment by a physiotherapist, who can identify any deficits (such as muscle weakness) and prescribe exercises to address them, is a good first step. A physiotherapist or certified exercise physiologist can also ensure you’re using the correct technique, so you’ll actually reap the benefits of a particular exercise (even if it’s walking or gardening), and point you towards classes in your community that are appropriate for you.

“Look for an instructor who can ensure that you have proper technique with whatever you’re doing and is able to give you progression,” advises Emma Smith, an exercise physiologist with the JointEffort program offered through Active Living at the University of Calgary. This means not only being able to provide you with gradually more challenging exercises when you’re ready (which is critical to muscle strengthening), but being able to modify specific moves to take into account any limitations you might have.

What if I have recurring knee pain and stiffness, or I’ve been diagnosed with knee OA?

If you have symptoms, see your family doctor or sports medicine physician to sort out whether you have OA or some other problem. (Sports medicine specialists and physiotherapists are also trained to identify misalignments in the knee—which can contribute to the development of OA by placing uneven pressure on the joint—and to prescribe measures to improve its positioning.)

If you do indeed have knee OA, all of the advice in the answer to the previous question still applies, and your doctor can refer you to a physiotherapist. However, there’s another option, as well: specialized classes such as the JointEffort program and those offered through GLA:D Canada—the Canadian branch of Good Life with osteoArthritis: Denmark —which are led by physiotherapists or certified exercise physiologists. (Some extended health benefit plans will cover the cost of GLA:D, which, at roughly $400 for two educational sessions and 12 sessions over six weeks, is still cheaper than an equivalent number of visits to a physiotherapist.)

In both programs, participants are given a customized set of exercises tailored to their needs and level of ability. They also learn that while exercise improves pain and function over the long-term, it’s normal for pain to increase during a workout; plus, they get guidance about how much pain is okay and when to stop, and how to tell if you’ve pushed yourself too hard and modify activities accordingly.

“Having someone knowledgeable watch over you, at least at the start, is the key to success,” Smith says. “The point behind GLA:D is that by six weeks, you should know what you’re doing and come out with a good knowledge base so you can continue on your own.” (Still, even after completing such a program, some people find it helpful to follow up with a physiotherapist or qualified personal trainer every six weeks or so to check their technique and make modifications to their regime.)

Whether you’re working one-on-one with a professional or participating in a class, however, it’s also helpful to set achievable goals and to log your activity and pain levels using an app or a plain old notebook. “A lot of people think, I’m not better, I still have pain,” Aldrich-Witt says, “but if you have the same amount of pain but you’re more functional, that’s progress. If your morning pain and stiffness goes down from six to four, that’s still a significant change. You need an objective record so you can go back and say, Oh, a month ago, I was doing only this.”

And if you work at it, you will reap benefits, whether they be better function after an upcoming knee replacement or the ability to do more of the activities you love.

While the degree of improvement obviously depends on a variety of factors, Lorne Hansen’s story demonstrates just how dramatic the results can be in some cases. As someone who skis (both cross-country and downhill), sea kayaks, cycles, rollerblades, and swims, the Calgary retiree had been very active until two years ago, when he began experiencing severe pain in one knee. Despite regular doses of ibuprofen, Hansen recalls, “I could barely get up a set of stairs, I was so sore.” When his sports medicine physician referred him to the JointEffort program, he says, “I was pretty skeptical.”

By the time classes had concluded, however, Hansen was a convert. Not only did he no longer need pain medication, but he was able to run up stairs and go back to using the pair of high-level racing skis he’d been on the brink of selling after his pain began.

“There’s no question it’s hard work,” he says, “but I’m very much a fan of this program. Osteoarthritis is ongoing, but my understanding is that you can certainly slow it down using proper nutrition, and with the exercises. You’re not going to get away scot-free, but you can really make a difference.”

Photo: iStock/Victor_69.