Your mind, body, and overall well-being can all benefit from getting your hands dirty

By Wendy Haaf

Visit the Canadian Tire in Amherstburg, ON, and you’ll probably meet garden-centre employee Diana Maretta, 62, whose co-workers have affectionately nicknamed her The Posy Pusher. For Maretta, gardening is a good deal more than a diverting hobby; it’s a method of managing stress, an incentive to get outside and engage in physical activity on a regular basis despite age-related aches and pains, a means of connecting with others, and even a way to bolster her family’s vegetable consumption.

A former breastfeeding counsellor, doula, and, until only a few years ago, competitive bodybuilder, Maretta gets a deep sense of satisfaction from sharing her knowledge about and passion for tending to plants. “The first summer in the garden centre, I think I did more talking about the love of gardening than I did telling people about perennials and annuals,” she says.

A growing body of evidence suggests that gardening and spending time surrounded by nature nurtures both physical and mental health, and that you can reap the benefits regardless of whether you share Maretta’s enthusiasm for planting flower beds and dividing plants. Here are just a handful of ways in which gardening can help your well-being flourish.

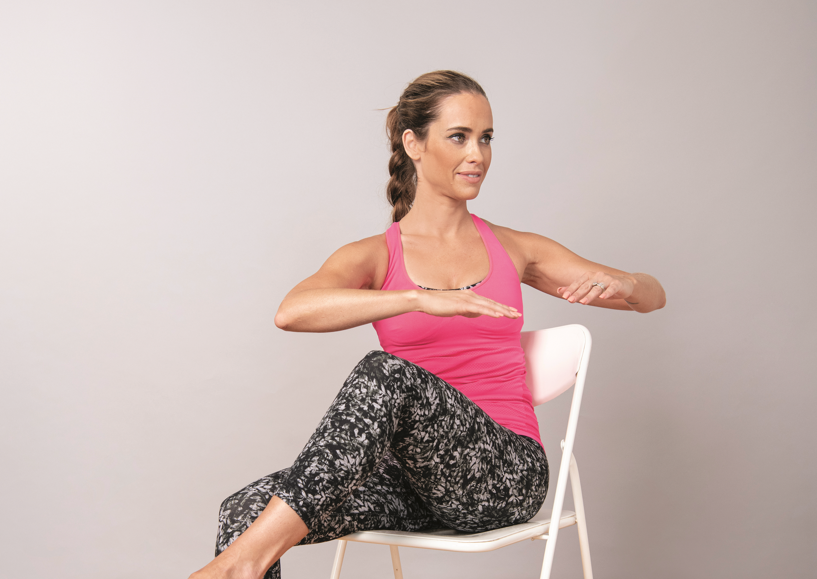

Combines aerobic, strength, and balance training

While most of us know that getting at least 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity a week improves heart and lung function, bolsters energy levels, facilitates healthy sleep, and reduces the risk for ailments ranging from cardiovascular disease to cancer, according to ParticipACTION’s 2019 report card, only 16 per cent of Canadian adults meet that goal.

“The vast majority of Canadians still aren’t getting enough physical activity each week to get the health benefits,” says Scott Grandy, an associate professor in the School of Health and Human Performance at Dalhousie University and an affiliate scientist with the Division of Cardiology at the Nova Scotia Health Authority. However, experts are beginning to stress that any amount is better than nothing, and if you’re not a fan of the gym or the yoga studio, gardening is a good go-to. (As with any activity, it’s best to start slow and gradually increase the length and intensity of sessions.)

“Gardening is what we would consider an endurance activity for your muscles,” Grandy says. “You’re not lifting the heaviest thing that you can, but you’re doing something that requires a level of strength, over and over.” In addition to helping maintain muscle mass and bone density, such activities foster the type of fitness that plays a large role in maintaining independence, he adds.

This is certainly true for Diana Maretta, who has adapted her gardening regimen to accommodate an injury and the physical changes that can accompany aging. “I make sure to pace myself, drink plenty of water, and take lots of breaks,” she says. “And when the boys at the store throw 10 bags of mulch into my truck, I get it out myself, even if it’s with a child-sized wheelbarrow or wagon.”

“If you go out and work in the garden, you’re probably walking around the yard a little bit, so there’s that aerobic component to it, as well,” Grandy says. “If you’re working the soil, you’re using your upper body; you’re standing up and squatting down, so you’re using your lower body. You may be squatting or bending over, so there’s a balance component to it, too. Gardening contains all the different components that we would structure into an exercise program, but instead of bringing you into a fitness facility and having you stand on one leg, or lift some low weights, or walk on a treadmill, we’ve changed that around and put it in a package that’s more enjoyable for you.” And that’s important. “We know that enjoyment and social connection are the main driving forces that determine whether someone will stick with a healthy behaviour or not,” Grandy explains.

Some research suggests that gardening may even have an edge over some other physical activities when it comes to fending off brain disease and increasing levels of bone-strengthening vitamin D in the blood. For instance, a 2006 Australian study that looked at activity levels in 2,805 men and women starting at age 60 over the course of 16 years—during which time 9.3 per cent of the men and 10.8 per cent of the women developed dementia—gardening was linked with a 36 per cent lower incidence of the condition. And in a study of 2,349 older Italian adults, those who spent at least an hour a week cycling or gardening had higher serum vitamin D levels than participants who did neither activity.

Before you grab your gardening gloves, be sure to cover up with clothing and apply sunscreen to protect yourself from UV exposure, Grandy urges. “You don’t want to trade off a benefit for another risk,” that of skin cancer.

Releases stress and promotes creativity and mental health

When Maretta looks out over her yard, each shrub or plant carries the memory of what was happening in her life at the time she planted it. “Gardening is therapeutic because it gives me something to do with myself when I’m worried and stressed,” she says. “It gives me a way to de-stress.”

It turns out these benefits are supported by science. Studies have found, for example, “certain chemicals that are released from plants as they degrade lower our levels of the stress hormone cortisol,” says Cheney Creamer, the chair of the Canadian Horticultural Therapy Association. And while these experiments grew out of a movement called “forest bathing,” you don’t necessarily even have to go outside to experience the effects. Creamer cites studies in which plants were placed in one of two windowless hospital radiology departments, each with identical workloads. “The results were astounding,” she says. “Stress leave was cut in half.”

One of the ways in which engaging with plants and the natural world seems to alleviate stress is by giving our brains a rest from the kind of fixed or directed attention that’s necessary for carrying out mental tasks. “There’s another type of attention called non-focused attention, which I refer to as ‘tourist vision,’” Creamer explains. “You know how when you get off a plane somewhere you’ve never been before and you just go, ‘Wow!’ and take it all in? That sense of awe or fascination is one of the times our brains get a break. And one of the things researchers find that bring us to this state of non-directed attention is nature.” What’s more, “they find that when we use our directed attention with nature, there’s no negative impact on our cortisol and stress system, such as occurs when we use our directed attention to look at our phone or read e-mails.”

This kind of reduction in stress seems to be linked to increased inventiveness, too. For instance, when certain bacteria that play a role in plant decomposition are introduced into a rat’s environment, the rodents are able to navigate a maze faster than usual—maze-solving is an animal model for creativity. “There are human extrapolations, as well,” Creamer says. When plant chemicals reduce stress levels, scientists reason, “our brain is actually able to function better and we’re able to have more innovative ideas,” she explains.

Even a momentary flash of green seems to have a similar effect; during an experiment in which participants leafed through an instruction booklet containing a single square of a randomly selected colour before performing a task, those who glimpsed a green square scored 20 per cent higher on measurements of creativity. (This study provides the backstory for the name of Creamer’s consulting and horticultural therapy business: One Green Square.)

The simple acts of planting, pruning, and digging support mental well-being in other ways, too. For starters, they involve exertion. “We know that physical activity is very good for mental health,” Grandy notes. “We know that it reduces things such as depression and anxiety, and there’s research to show it can actually boost cognitive performance and help prevent cognitive decline.”

For example, in a 2016 UK study that measured self-esteem, mood, and general health in 136 community gardeners before and after a session, not only did gardeners see an increase in self-esteem and mood after the activity, as compared with the control group, but they also had significantly higher self-esteem, lower mood disturbance, and better general health. They also experienced less depression and fatigue, as well as greater vigour. Another study, which examined levels of various types of physical activity and shut-eye in nearly 430,000 adults, revealed that gardening was linked with healthier sleep habits and a lesser likelihood of insufficient slumber (under 7.5 hours nightly).

Fosters a sense of purpose, success, and hope

One of the reasons Maretta finds gardening comforting is that “it gave me purpose when I didn’t feel that I was making any headway in other things in my life,” she observes.

And while the responsibility of caring for a living thing is likely valuable for anyone, it seems to be especially powerful for people who are living with mental-health and addiction issues.

This is one of the concepts behind the therapeutic garden and horticulture program at Vancouver General Hospital’s Willow Pavilion, which is part of the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority’s adult tertiary mental-health and substance-use department. Roughly 75 to 80 per cent of the mostly long-term residents have schizophrenia, and the same proportion have a history of concurrent, long-standing substance use, as well as histories of horrific abuse and trauma. As such, these patients “have probably been through every other facility that we have in Vancouver,” explains Leo Gosselin, who is the vocational rehabilitation coordinator there. Inspired by visions of creating a blossoming rooftop garden for a new nine-storey building, Gosselin began delving into the research behind using gardening as a tool for treating mental-health problems. “It was pretty clear that horticultural therapy was evidence-based, and it’s been used for a long time,” he says.

While it’s only beginning to sprout, the program is showing promise. “Clients enjoy the opportunity to see the results of their work,” such as dividing tropical plants and propagating succulents, notes horticultural therapist Moira Solange. “You get feedback from plants on whether you’re doing it right, and in that sense, the gardening is rewarding.”

Solange says she’s also seen some of the participants begin to grow and flourish; for example, one resident who initially took on the responsibility for watering has now assumed similar duties for new seedlings, while another resident was surprised and proud she was able to cultivate and nurture a sturdy plant. Gardening, says Solange, gives participants opportunities to cultivate healthy recreational habits, as well as a chance to take part in the community. “I think all people want to give to others and contribute in some way to those around them, to society,” she observes. Propagating plants for fellow residents as well as common areas and other parts of the hospital does just that.

In addition to allowing people to learn marketable skills, vocational and educational programs such as the hospital’s therapeutic garden and café “do more than just show people how to grow plants or make coffee,” Gosselin says. “They build confidence, and empower clients and give them hope.” Being able to germinate a plant and nurture its growth successfully “can be a starting point to build confidence in doing other things and to allow participants to feel the possibility they can be successful in other areas, as well,” Solange says. “Our hope is that we can instill pride and curiosity so that we can get clients engaged in other programs, such as dealing with addictions for transition into the community,” Gosselin adds. “The program has big potential for flourishing, to create a beautiful garden.”

In Cheney Creamer’s experience, using horticulture to help achieve a therapeutic goal can lead to breakthroughs in a relatively short time. She tells the story of a corporate stress management workshop she facilitated soon after incorporating horticultural therapy into her practice.

“Some of the people signed up on their own, but others were told, ‘You’re stressed, you need to go,’” Creamer recalls. One participant, obviously not there by choice, glowered most of the day, arms crossed, practically stomping his way through an outdoor activity Creamer had designed: “I told them, ‘This might sound a little bit crazy, but I want you to find any natural object that you’re drawn to—it doesn’t matter whether it’s a blade of grass, a rock, or a tree—and have a conversation with it. See if it has anything to say to you, and decide what you want to say to it.’ This person [the unwilling participant] is huffing and puffing and he literally starts kicking at the grass under his feet and muttering under his breath.”

After several moments, however, the man’s demeanour began to change as he relaxed and uncrossed his arms, and the furrows in his brow began to smooth. Once back in the conference room, the formerly angry-looking fellow asked if he could share something with the rest of the group. “He said, ‘I thought this was the stupidest thing anybody ever asked me to do,’” Creamer recalls. “He said, ‘I started kicking the grass and wondering why on Earth I would have a conversation with grass; it’s beneath me, it’s small, I don’t care about what it thinks, I have no need to listen to it. It’s irrelevant to me. And in that moment, I realized that I think that’s how I treat my staff.’” Initially, Creamer believed such a transformational insight was a rarity. However, “Now that I do this work on a regular basis, I’ve seen that it’s actually normal,” she says.

Nature, Creamer says, “really helps people deal with change. It has a fascinating way of feeling very permanent and unchangeable, and yet it’s constantly going through massive changes. It’s in a constant state of adaptation.

“Horticultural therapy also reinforces lessons about self-care and learning about caring for something outside yourself.” One area for which it’s been particularly successful, according to Creamer, is in treating post-traumatic stress disorder in veterans. “Being able to create life and allowing it to thrive seems to be incredibly emotionally healing,” she says.

Photo: iStock/skynesher.