Exercise will help ward off osteoarthritis—and help treat the condition should you get it

By Wendy Haaf

Photo: iStock/Zinkevych.

While research has begun to shatter many long-standing assumptions about osteoarthritis (OA), the news has failed to reach many doctors, much less members of the general public. For example, many people still believe it’s a normal part of aging caused by wear and tear on the cushioning cartilage in our joints and that exercise accelerates its progress. In fact, while it may be less dramatic than more aggressive forms of inflammatory arthritis, OA is a disease, and exercise plays key roles in both preventing and treating it.

For starters, regular weight-bearing exercise, such as walking and climbing stairs, is critical for keeping the cartilage in our hip and knee joints healthy. That’s because unlike muscle tissue, cartilage doesn’t have a blood supply to deliver nutrients and remove waste products. Instead, like a sponge, it needs to be “squeezed” regularly and repeatedly so it can absorb what it needs from the fluid bathing the joint. Our sedentary modern lifestyle may have helped contribute to the burgeoning numbers of people with OA: one study, in which scientists examined the skeletal remains of 2,500 people from different historical eras, found that the prevalence of knee OA has doubled since the Second World War.

Research in both humans and animals hints that weight-bearing exercise also helps bolster or at least preserve cartilage thickness. “Your cartilage is meant to bear weight,” says Jackie Whittaker, an assistant professor in the Department of Physical Therapy and the research director at the Glen Sather Sports Medicine Clinic at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. “That’s how it thrives.”

Exercise also eases mechanical strain on the hip and knee joints by strengthening the surrounding muscles. “When your muscles are stronger, you load your joints better,” Whittaker explains.

More Obesity Equals More Knee OA

So what goes wrong in someone with osteoarthritis? For reasons we don’t yet fully understand, “there’s an imbalance between the breakdown and the repair in the tissues of the joint,” Whittaker says.

What we know is that there are factors that can hasten the resulting degradation of the cartilage, including a history of injury to the joint.

“Evidence suggests that a combination of trauma, the production of harmful biological molecules, and a misalignment of your joints in knee osteoarthritis can accelerate the process,” says Mohit Kapoor, a senior scientist and the director of the Arthritis Research Program at Toronto Western Hospital’s Krembil Research Institute. There’s also some evidence that activities that exert prolonged stress on the knees or hips over many years—such as occupations involving a great deal of squatting, kneeling, standing, or carrying heavy objects—may also be linked with an increased risk. By contrast, long-time runners may actually enjoy a reduction in the risk for knee osteoarthritis, provided they don’t injure that joint.

A much more common trait that has emerged as a major risk factor, however, is obesity, and not entirely for the reason you’d assume. Yes, every extra pound of body weight places the equivalent of four pounds of pressure on your knee every time you take a step. But that mechanical stress is only part of the story. It’s not just a high body mass index (a fitness calculation that takes into account both height and weight) that’s connected with an increase in OA risk; it’s also the amount of fat tissue.

“There’s evidence that fat generates certain sets of molecules that are harmful—they’re actually instrumental in degenerating our joints,” Kapoor explains. “They cause inflammation and drive degeneration of the joints.”

One of the many reasons that exercise becomes doubly important once you develop osteoarthritis is that it directly dampens this simmering threat. “We know that small bouts of exercise decrease that low-grade systemic inflammation,” Whittaker says. And independent of its effect on weight (which is far more modest than that of diet), exercise can also help shrink fat mass.

The cartilage-preserving effects of repeatedly loading the joints via exercise become even more crucial if you have osteoarthritis, too. “The biggest mistake that somebody with knee or hip OA can make is to stop weight-bearing exercise,” Whittaker says. Exercise helps prevent or at least minimize disability by maintaining the flexibility and muscle strength you need to stay mobile and carry out everyday activities. Furthermore, over time, exercise helps dial down the discomfort due to knee or hip OA, both during activity and at rest. “There’s increasing evidence that exercise is helpful in decreasing pain and improving joint motion,” Kapoor says. The jury is still out on whether one type of exercise is better than another, but walking, strength training, and resistance exercise—alone and in combination—and tai chi all appear to offer benefits.

However, if you start experiencing pain and stiffness in your knee or hip that ramps up when you walk, garden, or do other physical tasks, the natural reaction, whether due solely to pain or to worry that it’s a sign of worsening damage, is to avoid such activities. According to Whittaker, the pain and stiffness associated with osteoarthritis of the knee and hip (the former being the most commonly affected joint) “is one of the main reasons people become inactive as they age.”

Another mistake people commonly make, she adds, is assuming that surgical replacement of the joint is the next logical step after being diagnosed with knee or hip osteoarthritis. “I’m not saying that joint replacement isn’t important or doesn’t have a role to play, but it’s very much an end-stage treatment,” she stresses. “We like to think of the approach to treating OA as sort of a pyramid: if you do the right things in the right order, fewer people will need surgery, and those who have the surgery will fare much better.” The evidence supporting this approach is so strong that, Whittaker says, “it’s one of the few things we actually have international consensus on.”

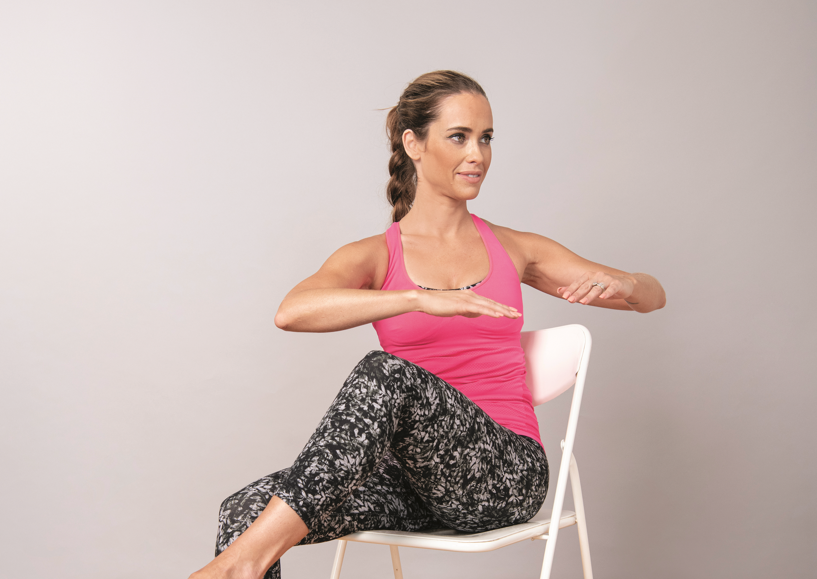

Exercise Therapy

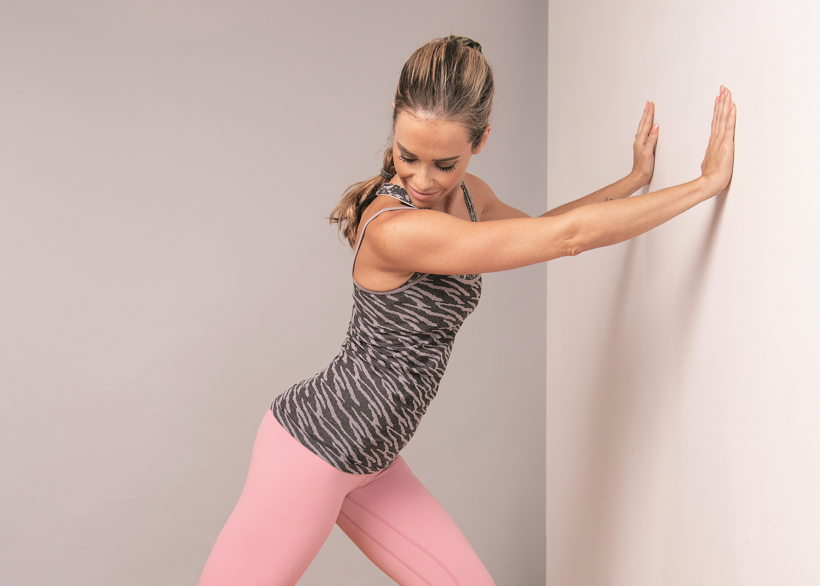

One of two components forming the base of that pyramid is exercise therapy, with the type and dose tailored to a person’s needs. Initial instruction on how to perform the exercises properly and education on such things as how to get up off the floor, do a squat, and climb stairs correctly also play key roles.

While it’s ideal to get this type of personally tailored advice and instruction from a knowledgeable physiotherapist (or in some cases, a specially trained kinesiologist or exercise therapist), such services typically aren’t covered by provincial health plans, putting them out of reach for many people. But, Whittaker says, “there are a lot of innovative ways in which people are trying to make exercise therapy for people with OA more accessible.”

One such example is the GLA:D (Good Life with osteoArthritis: Denmark) program, which consists of two teaching periods plus two weekly 90-minute exercise sessions over eight weeks. Developed in Denmark and now being rolled out in Canada, GLA:D has “been run with thousands of patients, and researchers have produced quite a few papers that have been published in very prestigious journals showing that this program works, and works well,” Whittaker says. And the cost—in the neighbourhood of $400—which is covered by some extended medical plans, “is quite a bit less expensive than going to a physiotherapist,” Whittaker says. In centres where clinical trials of the program are being conducted, it’s available for free to participants who meet study criteria.

“Probably the most important thing you learn is how to change your dose of the exercise depending on what’s going on in your body,” Whittaker says. “The reality is that it’s very normal and expected that somebody with knee or hip OA will get some pain when he or she starts doing the exercises.” So for example, if your pain level climbs from three out of 10 to seven during class, that’s a signal to stop and consult your instructor or physiotherapist about how to modify what you’re doing. A bump from three to five, however, is a green light to stay the course (as long as the pain returns to baseline within 24 hours). Taking an appropriate medication before starting an exercise session can help moderate pain—ask your family physician, specialist, or pharmacist which option is most suitable for you.

Exercise Yields Results

In some cases, this combination of self-management skills and graduated exercise can stall the progress of OA and at least significantly postpone the need for joint replacement surgery. But even when it doesn’t, the results are worthwhile.

For example, Patricia Johnston of Edmonton says participating in the inaugural session of that city’s GLA:D program enabled her to get up and down from the floor with minimal assistance—something severe OA had previously prevented her from doing—and improved her walking ability while she was awaiting bilateral joint replacement surgery. “It makes it so a person can at least manage and have a little bit of quality of life,” she says.

What’s more, this kind of preparation helps people like Johnston reap more benefits from the operation than they would otherwise. Without it, “what we find with people who have joint replacement surgery is that their physical activity levels and their functions don’t improve dramatically afterwards,” Whittaker says.

That’s certainly not the case for Johnston, who, just four months after undergoing an operation to replace both hips, had already begun to resume the kind of active lifestyle the former cyclist, Rollerblader, and hiker once enjoyed. While the artificial joints rule out a few specific movements such as those involved in jogging and certain yoga positions, yoga itself is something Johnston can pursue. “I’ll be able to do lots of activities,” she says, “and without pain.”

Resources: