From Linda Priestley, Editor-in-Chief

Ten years ago, civil servants in Melbourne, Australia, invited citizens to alert them to any problems such as disease or rotten limbs affecting the city’s more than 70,000 trees, each of which had been assigned its own ID number and email address. Instead, Melburnians began writing to their favourite oak, eucalyptus, or acacia to express their appreciation or simply say hi. (“How are you today, old tree? I’m doing okay.”)

While they were at first a bit surprised by this response, city officials decided to answer the emails—as if they were the tree in question. The experiment was so popular that it was extended. During the pandemic, the city encouraged those who were unemployed to stroll beneath the trees and thus motivated many city dwellers to reconnect with nature.

If you’re part of the #igrewupinthe70s generation (or the generation before that), you probably climbed trees (even in an urban area), stole beans from the neighbour’s garden, or ate worms (well, not you, but your little brother or sister, of course). Today, though, we don’t pet caterpillars or jump in haystacks; we tend to be more attached to our screens than connected to the environment, studies say.

We have Nature-Deficit Disorder, a term American journalist Richard Louv coined and introduced in his bestseller Last Child in the Woods. Yet connection with the great outdoors is essential, for both morale and longevity—so essential that, under the PaRx program launched by the BC Parks Foundation and now supported by Parks Canada and the Canadian Medical Association, more and more Canadian doctors are writing prescriptions for their patients to visit parks, recommending activities and specifying the frequency and duration of visits.

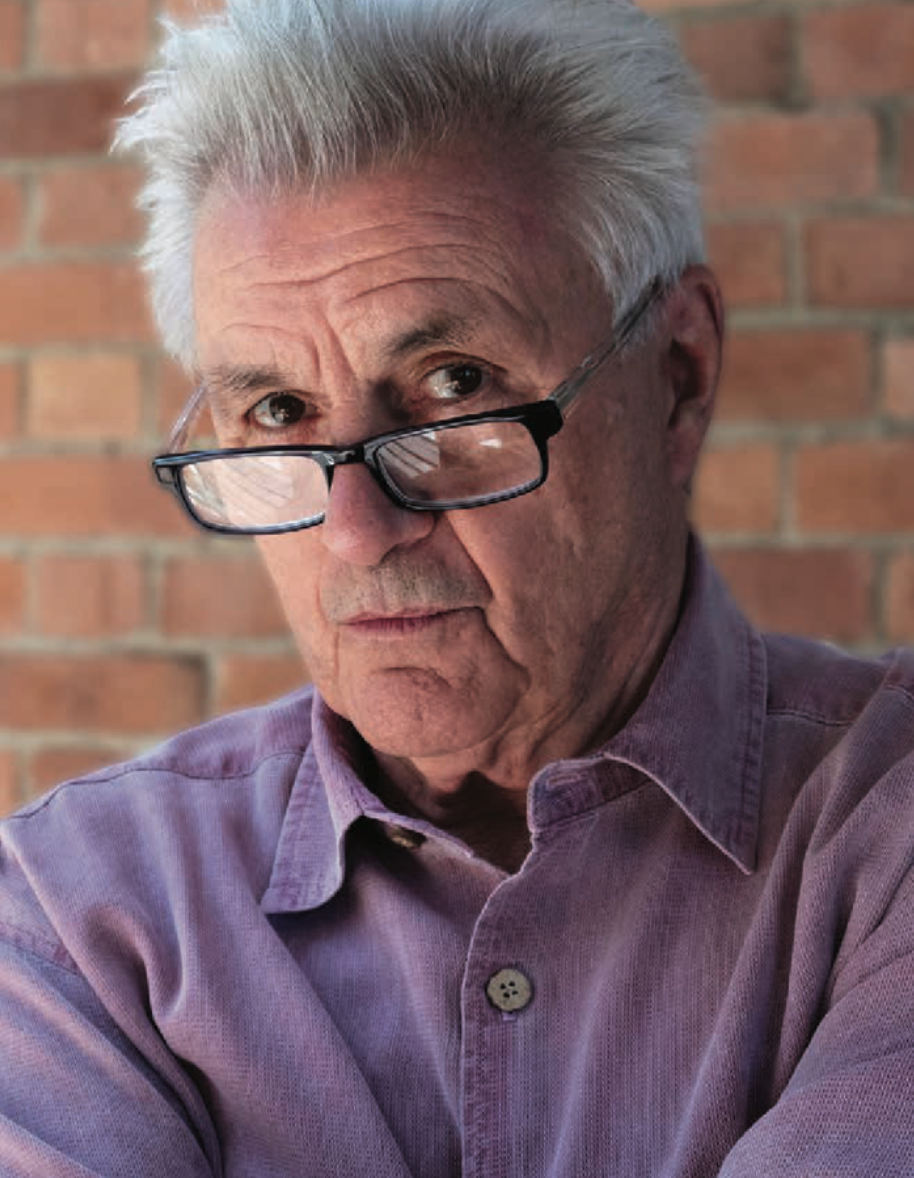

Our sense of connection to nature is, in fact, a matter of our survival: even if the planet recovers from our abuse, that abuse has been accelerating the process of our own extinction, says David Suzuki in “A Voice for Nature.”

However, he points out that it’s not too late to take action. You can start by heading outside as often as possible, walking among (and perhaps talking to) the trees, roaming through parks, woods, and the countryside with your children and grandchildren, letting a spider walk around on your hand, milking a cow….

If you want some ideas to help you connect, read Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, find out what other cultures do to commune with the outdoors, or visit the Facebook page of the Canadian Ecopsychology Network, an online space for sharing and learning to strengthen our ties with the earth. Forging a connection with the natural world means saving our souls and our skins.