Here’s what you need to know about keeping your bones healthy for a healthy, independent future

By Wendy Haaf

Photo: iStock/LittleBee80.

Osteoporosis—the disease that silently sabotages bone strength—strikes only 80-year-olds, right? And it doesn’t affect men, right? Wrong.

These are just two of the misconceptions that experts on this potentially debilitating condition encounter every day, and not just among the general public, but among physicians, as well. Unfortunately, these untruths can prevent people from taking steps to protect their bone health and fend off life-altering fractures. So what are the facts? Here are 13 things you might not know about osteoporosis and bone health.

1. Osteoporosis is surprisingly common. This is true even if you consider only the most serious consequence—fractures—and in just half the population: in Canadian women, osteoporosis-related fractures are more common than heart attack, stroke, and breast cancer combined, according to Osteoporosis Canada.

2. We all begin losing bone before age 55. Roughly around age 40, there’s a change in the normal, continuous cycle of bone renovation. The cells that act as bone-builders gradually begin to lag further and further behind the demolition crew. In women, this imbalance accelerates at menopause, when the production of bone-protecting estrogen plunges. That’s why female gender is the second biggest predictor of fracture, after age.

3. Some of us start with sturdier bones than others. The third major risk factor—bone density, or mineral content—is influenced by your genes. “There’s a genetic component that explains around 70 to 80 per cent of where a person’s peak bone density reaches when they’re in their 20s or 30s,” says Dr. Emma Billington, a professor in the Division of Endocrinology at the University of Calgary’s Cumming School of Medicine and associate medical director of the Dr. David Hanley Osteoporosis Centre. This may be one reason a family history of hip fracture (e.g., in a parent) is a strong risk factor for osteoporotic fracture.

4. Osteoporosis doesn’t affect only the elderly. In osteoporosis, the supporting framework inside bone gradually becomes thinner and more flimsily constructed. By the time a fragility fracture occurs, the deterioration has been under way for a long time.

For that reason, even though most fractures occur after 75 (for instance, three-quarters of hip fractures occur after this age), 55 is a good time to take stock of your bone health and work on changing any modifiable risk factors. At the same time, bone loss can start earlier still and progress more quickly for a variety of reasons, leading to fractures even before 55.

5. Several conditions, medications, and lifestyle habits can speed bone loss or hinder the rebuilding of bone. Risk factors other than age include conditions that impair one’s ability to absorb nutrients (such as celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and colitis), disorders linked with more rapid bone loss (such as rheumatoid arthritis, COPD, and kidney disease), and taking medications that can impair bone health (primarily corticosteroids and hormone blockers used to treat and prevent the recurrence of breast and prostate cancers, and possibly SSRI antidepressants, PPI heartburn/ulcer medications, and some blood pressure drugs).

A sedentary lifestyle is also linked with an increased fracture risk, since walking and other forms of exercise prod the bone-building mechanisms to keep working.

6. Men get osteoporosis, too. While osteoporosis is more common in women, that doesn’t mean men are immune. According to Osteoporosis Canada, at least one in five men will break a bone due to osteoporosis over a lifetime, versus one in three women. (All of the risk factors noted above apply to both sexes.)

However, some risk factors in men are slightly different, notes Dr. Suzanne Morin, who is an associate professor in the Department of Medicine at McGill University and a scientist with the Centre for Outcomes Research and Evaluation at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre in Montreal. For one thing, men are more likely than women to smoke and to drink three or more units of alcohol a day—both of which increase risk. In addition, “some conditions whereby you lose calcium in the urine are more common in men,” Morin says. These disorders, such as low testosterone and Type 2 diabetes, “create more rapid bone loss and can cause early bone deterioration and early fractures,” she adds.

7. Osteoporotic fractures are a much bigger deal than you might think. “Hip fracture is a game changer regardless of age—not just for you, but for your family,” says Dr. Alexandra Papaioannou, the director of the GERAS Centre for Aging Research at Hamilton Health Sciences Centre and a professor of medicine at McMaster University. Aside from the fact that one-third of people who have such an injury die within one year, more than 60 per cent don’t regain their previous walking ability—hip fracture is one of the leading causes of admission to long-term care. Even if you’re one of the lucky ones, mobility is often reduced and “you need more care, and you’re not a happy person because your quality of life is not as good,” Papaioannou adds.

But even what might seem less-serious fractures—the compacting of vertebrae—can also cause havoc, although until relatively recently, “we didn’t understand the big impact it has on people’s lives,” says Papaioannou. For one thing, unlike hip fractures, compression fractures can’t be repaired surgically. And since vertebral fractures don’t always cause obvious symptoms, they can often go unnoticed until someone has accumulated several such breaks. “When people have a number of fractures in their back, the pain level is very difficult to manage,” she explains.

A curved spine and loss of height—once considered a normal part of aging—are clues that hint at multiple vertebral fractures.

8. You don’t need tests to estimate your risk of fracture if you’re under 65. Using an online tool called FRAX, “you can calculate your own fracture risk based on lifestyle factors and genetics,” Papaioannou explains. (Visit osteoporosis.ca and search for “FRAX.”) Just make sure you’re using the Canadian version, since the weight of various risk factors varies by country—and carefully read the descriptions for each item.

If you’re 65 or older, the addition of another piece of data provides a more complete picture of fracture probability: “We recommend that everyone get a baseline bone density test at around age 65 for women and 70 for men,” Papaioannou says, “because your risk goes up at that point.”

But where are the boundaries between different risk categories drawn? Someone with a 20 per cent chance of experiencing a fracture over the next 10 years is considered high-risk, 10 per cent is deemed low-risk, and anything in between falls into the moderate-risk category.

9. There’s more to a bone-healthy diet than getting enough calcium and vitamin D. Yes, adequate amounts of these nutrients are necessary to maintain bone, since calcium, which is one of bone’s mineral building blocks, can’t be absorbed by the body without sufficient amounts of the so-called sunshine vitamin. Currently, Health Canada and other organizations recommend that healthy men under age 70 consume 1,000 milligrams of calcium each day, and that healthy men over age 70 and all healthy women consume 1,200 milligrams daily; recommendations for vitamin D are 600 to 800 IU daily, preferably from food, for adults under 70.

For the 1,000 milligram target, that’s roughly three servings of dairy (300 mg each) plus 300 from other sources in a varied, healthy diet, says Wendy E. Ward, a professor of kinesiology and health sciences and a Canada Research Chair in bone and muscle development at Brock University in St. Catharines, ON. (To see how much calcium you’re consuming, use the osteporosis.ca calculator.)

Vitamin D, however, is more challenging. “There’s not a lot of vitamin D in our food supply,” Ward notes. For instance, milk, which is fortified with vitamin D, contains roughly 100 IU per cup. Since most people get only about 200 milligrams a day through their diet, it’s probably prudent to take 400 to 600 milligrams in supplement form to make up the shortfall. On the other hand, it may be a good idea not to exceed the 2,000 IU recommended upper limit, since a recent study hinted that very large doses (4,000 mg and above) may actually speed bone loss.

Protein has also been linked to sturdier bones, and overall diet quality may count, too. According to Ward, in population studies, eating patterns similar to the DASH and Mediterranean diets “seem to be a marker of overall better bone health.” (One international group of experts on nutrition and aging recommends healthy older adults aim for at least 1–1.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight a day, ideally divided equally over meals and snacks.)

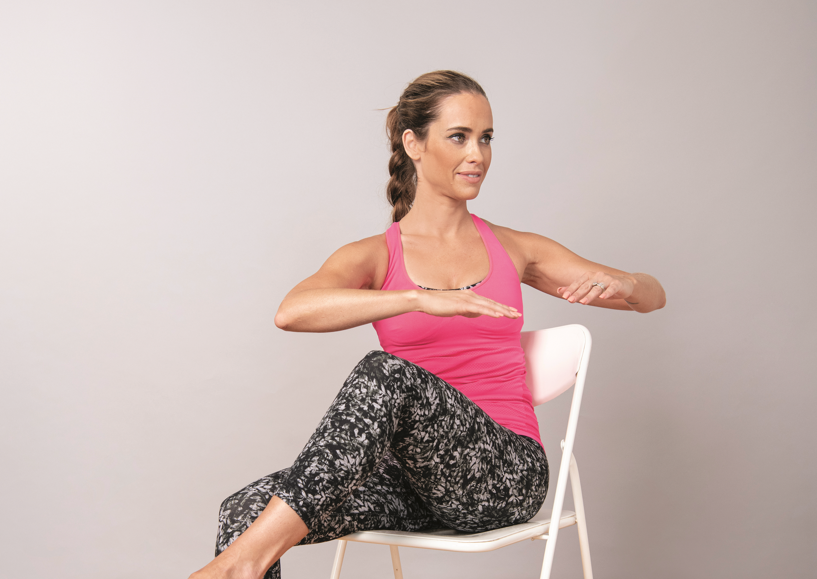

10. Weight-bearing exercise isn’t the only type experts recommend to reduce fracture risk. We’ve known for some time that exerting stress on bone via weight-bearing exercise prods the body’s “stonemasons” to keep working. More recently, however, evidence has accumulated showing other forms of exercise help prevent fractures, too. “Walking is good, but resistance training and balance exercises a few times a week are recommended,” University of Calgary’s Dr. Emma Billington says. Resistance training not only protects bone quality, it also maintains muscle mass and power, and balance exercises reduce the risk for falls.

“Bone strength is just part of the equation—the muscle part is just as important,” McGill University’s Dr. Suzanne Morin emphasizes. And if you’re trying to lose weight, exercise is even more crucial—along with adequate protein—to prevent muscle loss, adds Dr. Angela Cheung, the director of the University Health Network’s osteoporosis program, a Canada Research Chair in musculoskeletal health, and a professor of medicine at the University of Toronto.

An evidence-backed program called Bone Fit incorporates all three forms of recommended exercise. You can access it through specially trained physiotherapists and kinesiologists, many local YM/YWCAs, and via videos on Osteoporosis Canada’s website.

11. If you’re over 40, breaking a bone—even as a result of a fall—signals that your bone health is probably compromised. “If you break something when you slip and fall, don’t brush it off as an accident,” Cheung urges. “It’s no different from having a heart attack when shovelling snow.” In other words, such an event strongly suggests the existence of an underlying problem that warrants further scrutiny. In this case, that means asking your doctor to have your bone health assessed, which, in addition to reviewing your risk factors, may include blood tests and a DXA (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) scan to measure your bone mineral density.

Don’t wait too long after a fracture to seek these answers—as with heart attacks and strokes, the first year or two after a fracture is when people are at the highest risk for a repeat event, Papaioannou explains. And that’s no small matter: research suggests that half of hip fractures are preceded by such a warning break.

“If you slip and fall and break something, please have your bones assessed so we can make that fracture your last,” Cheung urges. “It’s the repeat fracturing that really decreases quality of life, function, and mobility.”

12. Preventive treatments have never been better. First, the oldest class of osteoporosis medications now come in a variety of administration methods and dosing schedules, so you can choose the one that’s most convenient for you—daily, weekly, or monthly pills; bi-annual injections; or yearly infusions. (Called antiresorptive agents, these drugs bolster bone strength by improving mineral deposition and slowing deterioration.) Newer (albeit far more costly) drugs actually build bone.

Overall, osteoporosis treatments “work quite well,” Cheung says. “Depending on the fracture, they reduce fracture risk from half to as much as three-quarters.”

Doctors have also gained a more nuanced knowledge of how best to use bone-protecting drugs, from stopping after a certain period to further minimize the chance of already rare serious side effects, to using a limited course of one type to build bone, followed by a course of another type to slow bone loss.

13. You should see your doctor if you fall twice or more in one year. Reviewing your medications (including over-the-counter products) can help determine whether one or a combination could be impairing your balance. Low levels of vitamin B12 and too-low blood pressure are other potential, easily fixable culprits. And if you haven’t seen your optometrist recently, an eye check is in order; if you wear eyeglasses or contacts, you may just need your prescription changed. In some cases, having an occupational therapist visit your home to identify falling hazards is helpful, too.

“People become fearful they’ll lose their independence when they start falling, but there are things we can do to make you stronger,” Papaioannou stresses. “It’s never too early to start balance and resistance training and never too late. I have 90-year-olds who start working out, and they’re role models to me and to others.”