One of Canada’s most esteemed humanitarians believes that our future is up to us

By Peter Feniak

Peace has not come easily to Lieutenant-General (ret.) Roméo Dallaire in the 30-plus years since he served in Africa as Force Commander of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda.

“I promised never to let the Rwandan Genocide die,” he has said. “I felt it was my duty to talk about it… keep it going.” The horrific events he witnessed live on in films and in Dallaire’s own writing. And after many cruel years, it is finally understood that Rwanda also left him with severe post-traumatic stress disorder—PTSD. “If I can find peace,” he writes in his latest book, “anyone, maybe everyone, can.”

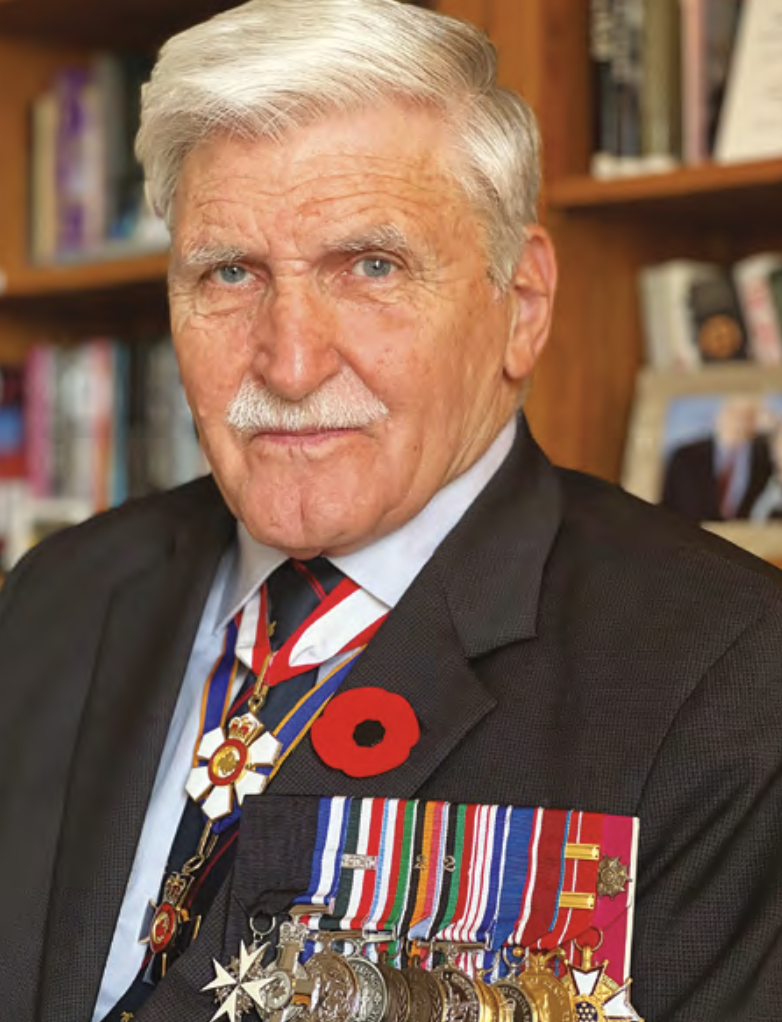

Today, Dallaire is an author, speaker, activist, former Canadian senator, and, as CTV News noted, “one of the world’s leading humanitarians.” The robust retired general with the bushy moustache and piercing blue eyes has fought hard for his causes over decades. The Peace: A Warrior’s Journey, written with Jessica Dee Humphreys (Random House of Canada, 2024), announces a striking new pathway.

Purgatory

As we connect by phone, Dallaire is relaxed and good-humoured. “I’m 140 kilometres down from Quebec City on the St. Lawrence, in this beautiful old village with the river and the mountains and farms, in an old seigneury that the British tried to burn down,” he says. It’s a 200-year-old home that he shares with his wife, Marie-Claude Michaud, a writer/consultant whose 25 years as a civilian in the Department of National Defence inspired her belief in the need for change. (Dallaire and his first wife divorced in 2019.)

The former executive director of the Military Family Resource Centre in Valcartier, Que., advocates for “human-first leadership” focused on the well-being and mental health of employees. The message resonates with Dallaire.

In his book, he names and laments the many obstacles that block the road to a better humanity. “To me,” he says, “we have ended up on this earth with a potential we’ve not even really touched.” He accepts that we may never reach that potential, but with climate danger, edgy international confrontation, political polarization, and the threat of nuclear war, he believes that we must try. “We can choose to come together and assist others,” he writes, “or isolate our- selves and ignore everyone else. It is our choice.”

The Peace benefits from Michaud’s energy, but it also bears the imprint of another inspiring figure: the 14th-century Italian poet Dante Alighieri. Dante’s classic narrative poem The Divine Comedy famously follows a wandering traveller through Hell, Purgatory, and, ultimately, Paradise. The structure of Dante’s poem “absolutely hit the target,” Dallaire says.

In The Peace, Purgatory is all that frustrates human progress, especially in global affairs. “How far a truce is from any meaningful conception of peace,” he writes. The United Nations is seen as a worthy body handcuffed by the vetoes of the permanent members of the Security Council—China, Russia, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. “Dedication to their own interests is high,” Dallaire writes. And nuclear stalemate keeps our world on edge.

Purgatory is a mountain-climb to a better world, a climb that never seems to end. But if a solution is found—and Dallaire has ideas on how that can happen—Paradise is possible.

“We can choose to shape the future,” he says, “or just survive.” Skeptics will shake their heads. “Of course it’s a dream, but human beings have got to find ways to respect one another other before it becomes untenable.”

Dallaire’s Paradise may be a distant dream, but Purgatory is real, as human actions cancel progress and real peace. Hell, undeniably, is what Dallaire experienced in the never-forgotten holocaust of Rwanda in 1994. That unforgettable tragedy comes to life again in The Peace.

Dallaire arrived in Rwanda as the commander of an international peacekeeping force. He was 48, an experienced and valued military officer. He now acknowledges that he and his command were ill-prepared, knew little about Rwanda, and could not understand what was to come. Incendiary extremism had spread, and hatred had grown from bitter tensions between the dominant Hutu ethnic group and the Tutsi minority.

As those tensions erupted into violence in April 1994, most of the world turned away. “France, Belgium, Bangladesh, and other UN members evacuated their troops in a startling show of self-interest,” Dallaire writes.

He was ordered to abandon his mission in a phone call from UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali, but he refused. As chaos engulfed Rwanda, Dallaire and his peacekeeping “blue helmets” did what little they could to save lives. They witnessed pure terror—a “bloodthirsty expression of hate generated such a level of violence so quickly that it destroyed almost a million people over only one hundred days,” Dallaire writes. “The machete [was the] terrifying weapon of choice; the killers left the bodies of their victims where they fell.”

Living With PTSD

In the wake of this tragedy, Dallaire returned to Canada a broken man. Signs of PTSD include pain, paralysis, insomnia, recurring nightmares, and frightening flashbacks that can strike without warning. Dallaire now carried that burden. “There was no way to laugh anymore, to love, to care, and [you lived with] a sense of guilt in having survived,” he told CTV News.

Dallaire saw dark days of despair, deep alienation, and public humiliation. He attempted suicide more than once. But he faced his crippling injury with determination. He sought medical help and found it. He became redefined, not as a victim but as a committed humanitarian. He had seen the frightening recruitment of children as drugged, brainwashed soldiers in Rwanda. Fighting that wrong became a passion for Dallaire.

He became an international voice against the hateful practice. Witness to his resolve is The Dallaire Institute for Children, Peace and Security at Dalhousie University in Halifax. Branches of that institute have emerged, including in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital city. The recruitment of child soldiers is now an international war crime.

As his stature grew, Dallaire was appointed to the Canadian Senate in 2005. He became a vocal advocate for veterans’ rights. Today, veterans and their families thank him for raising understanding of PTSD. In conversation, he becomes intense as he revisits the subject:

“It’s got to be perceived as a psychological injury—an operations stress injury. It’s an honourable and real injury! You’ve got to build the prosthesis with medication, peer support, and therapy just to pull yourself back together—as best you can. Because you will not return to what you were before! You may get close, but you will be different—and certainly November 11 proves that.” (Maureen Anderson, Canada’s Silver Cross Mother for Remembrance Day 2024, lost both her sons, Ron and Ryan, to severe PTSD after traumatic service in Afghanistan.)

Dallaire’s is a military family. He was born in the Netherlands in 1946 to Canadian Staff-Sergeant Roméo Louis Dallaire and Catherine Vermeassen, a Dutch nurse. He grew up in east-end Montreal in military housing, became an Army cadet, and joined the Canadian Armed Forces at 18. He graduated from the Royal Military College of Canada with a Bachelor of Science. His three children (Willem, Catherine, and Guy) have all had roles in the Forces. The general shares more of his story as we talk: “Going through therapy, I finally understood why my father was so physically abusive and drinking and never ever truly happy. There was always a sadness there. And I remember going to sleep at night hoping that God would take him away because he was just destroying us and the family. And I finally understood him. He had severe PTSD.”

Activism!

Dallaire became a powerful, engaging public speaker. He joined think tanks and advisory boards. He proved himself an articulate, heartfelt writer. His Shake Hands With the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda (Random House, 2004) won the Governor-General’s Award for non-fiction. Canadian and international honours came his way. So did a warning.

“I was committed; I was working full-time,” he says, “and I was told by my doctors that I was literally driving myself into a sort of camouflaged suicide. They said that the way I was living, I was lucky if I had two years left to live.”

Now, as part of his therapy, Dallaire has a treasured model train set at home and something he always wanted: an electric guitar. The goal is to recover memories of joy in childhood. He smiles, describing these “pauses in life you have to capture.” He had a cross-Canada book tour planned in 2024 to introduce The Peace, but a mystery illness post-poned it. Doctors discovered a rare virus, apparently contracted in Thailand years ago. Careful surgery was successful. “It pretty well ended in July–August,” Dallaire recalls. “And so they told me that I’m ready to go, no problem. All I have to do is get in shape, maybe cut a bit of booze. Between the ears, that’s another story. That’s always an ongoing battle.”

Years of therapy and medication have moderated Dallaire’s PTSD. His rural surroundings have also benefited him: “I have found serenity here—through love.” His energy is exceptional, as is his conviction. He partners with Michaud in workshops explaining the idea of bienveillance, roughly translatable as “good vigilance” or “benevolent watching over”: they promote “leaders as conscious of caring as they are of leading.”

He is proud of The Peace and of the new place he’s found in his life. He has also retained humour. “The love of this extraordinary woman has permitted me to grasp these concepts,” he says. “It’s only over the past few years that I have really started to coalesce my thinking.” He laughs, adding, “And that’s why it took me 10 years to write that goddamn book!”

And his answer to finding a pathway to a better world? “Activism! Activism! Activism! What’s gonna catch people by surprise is that women are not going to take the crap of a male-dominated world anymore,” he says. “And the men better start adjusting to the change as we move away from all these male-dominated institutions. And that’s going to be reinforced by the youth. They’re already global, these kids. They’re the generation without borders. [I believe] that we’re on the cusp of a real revolutionary era. I just hope humanity won’t need to self-destruct, like I almost did, to learn these lessons.”