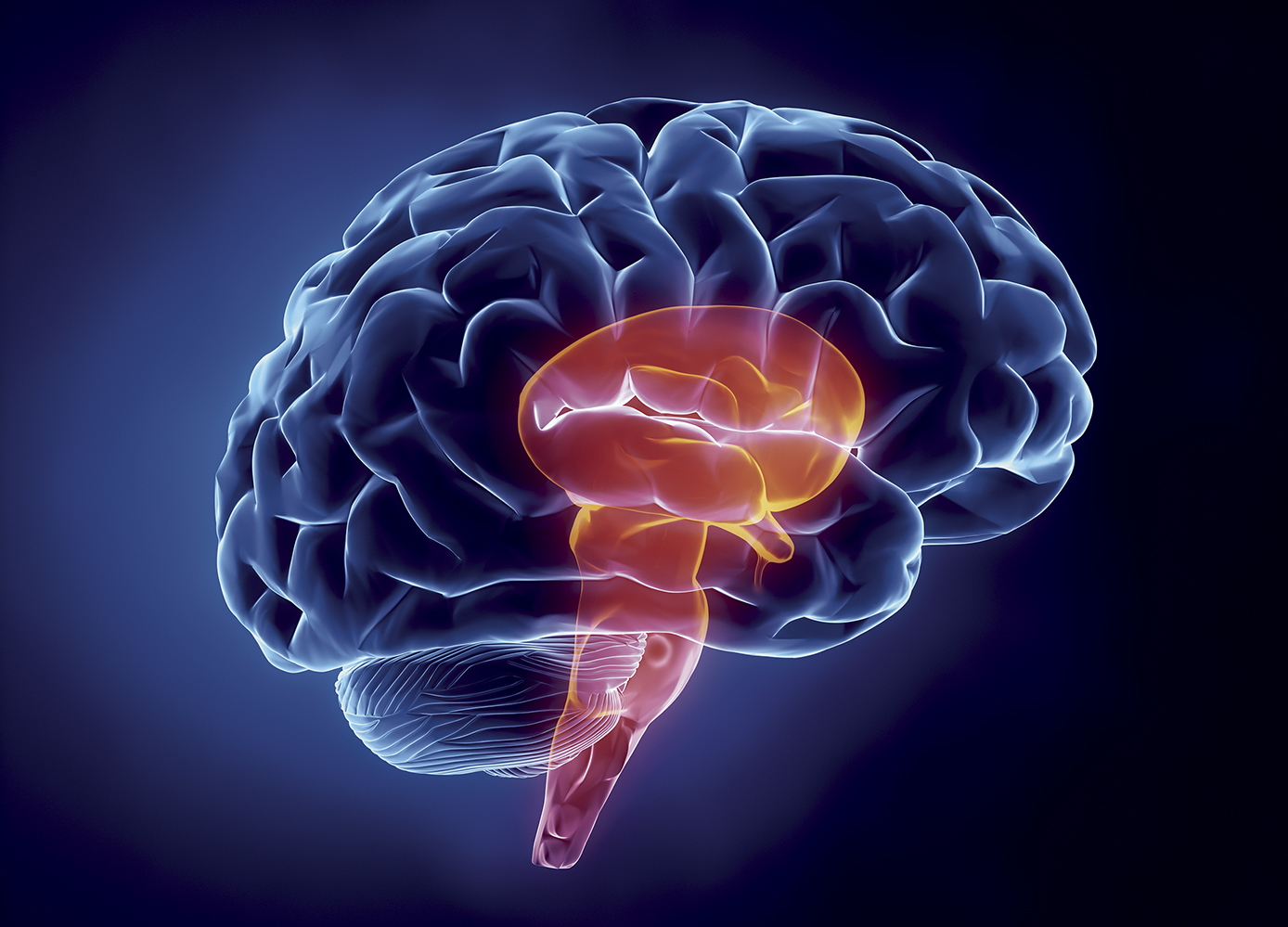

A brain-stem stroke is a very specific kind of stroke, with its own set of symptoms

By Wendy Haaf

A popular feature in Good Times magazine is Your Health Questions, in which we answer questions submitted by our readers about health, nutrition, and well-being, such as:

How does a brain-stem stroke differ from a stroke occurring elsewhere in the brain?

Given the brain stem’s size and anatomy and the functions it governs, brain-stem strokes (an estimated five to 10 per cent of strokes) can differ from those that occur in other regions of the brain in a few ways.

Symptoms. In addition to the usual FAST stroke symptoms (Face: is it drooping? Arms: can you lift both? Speech: is it slurred or jumbled? Time: call 9-1-1 now!), brain-stem strokes can cause symptoms that often include visual changes such as double vision, says Patrice Lindsay of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. “Other things are a combination of dizziness and vertigo—the sense of the room spinning around you—and significant balance issues. Any one of those can occur for other reasons, but together, especially with symptoms such as weakness on one side, they’re more likely to be a brain-stem problem.”

This unique pattern is due to the fact that the brain stem (which is also responsible for basic functions such as breathing, swallowing, and maintaining consciousness) is a tightly packed communications hub through which messages to and from other parts of the body are routed. Consequently, a severe stroke in this region can sometimes cause loss of consciousness, symptoms on both sides of the body (rather than on one side only), or, very rarely, near-total paralysis (sparing only eye movements). However, strokes in the brain stem don’t impair thinking.

Risk factors. While brain-stem strokes share many risk factors with those that happen elsewhere in the brain (such as high blood pressure and smoking), they can also be triggered by abnormal stress on the arteries that snake up through the bones in the back of the neck—something that can occur during a whiplash-type injury, such as that which might be sustained in a car crash or chiropractic manipulation.

“Brain-stem stroke is often missed after car accidents, because everybody is focused on the pain,” says Dr. David Spence, a professor of neurology and clinical pharmacology at Western University’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry and director of the Stroke Prevention and Atherosclerosis Research Centre at Robarts Research Institute in London, ON.

The long-term outlook after a brain-stem stroke depends on the severity and the specific location of the stroke, but overall, “brain-stem infarctions are usually more benign,” Spence says. “It may take six months to a year, but people tend to recover better.”

And while a stroke ups the chance of another occurring in the future (and with it, complications such as cognitive changes that can lead to dementia), eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, and controlling such risk factors as diabetes, atrial fibrillation, and blood clotting problems “can reduce the risk for a second stroke,” Lindsay says.

Photo: iStock/janulla.