by Olev Edur

If you intend to pass some of your wealth on to charity, you need to make that part of your estate planning

When it comes to charitable giving, Canadians are a generous lot, especially seniors—many of whom have a list of charities to which they routinely donate. But figuring out how to include charitable causes in their estate planning is another matter.

“A lot of retirees are very philanthropic, but they’re not sure where to start when it comes to making large donations through their estate,” says Christine Van Cauwenberghe, head of financial planning at IG Wealth Management in Winnipeg. “They’re used to making modest donations each year and don’t understand how making large donations can affect their estate. If you know you’re going to make a large charitable donation, though, making it in your will is a good way to reduce your final tax bill. That way, more of your estate will go to those whom you want to benefit rather than to the government.”

Reducing Taxes

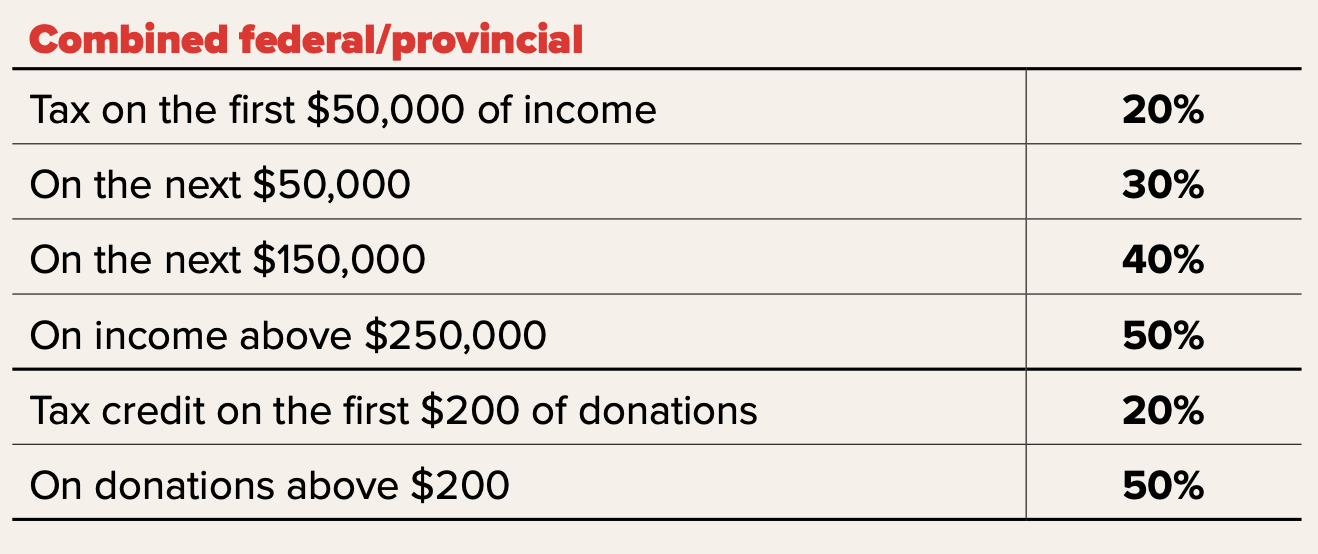

How does this arrangement work? For starters, it’s important to understand the basic rules regarding charitable donations. The first $200 of your donations each year qualifies for a federal tax credit of 15 per cent; anything above $200 qualifies for a 29 per cent federal credit.

“There are added credits for those whose incomes are higher than about $250,000, and then there are provincial tax credits,” Van Cauwenberghe says.

Donations cannot equal more than 75 per cent of net income in any given year, but that limit rises to 100 per cent of net income in the year of death. The tax credits are non-refundable, meaning they can be used only to reduce your taxes. “You can, however, carry unused credits forward for up to five years,” Van Cauwenberghe says.

“People sometimes have events in their lives, such as selling a house or other large asset, and this could lead to a large capital gains tax bill. You do have the principal-residence exemption for your home, so it can be passed on tax-free, unless you want to use the exemption for another property, such as a cottage. Otherwise, the tax bill could be sizable, because if you sell a large asset, your capital gain is subject to a 50 per cent inclusion rate [meaning one half needs to be included in your income]. So, if you’re planning to make a large donation, you should make it in the same year as the sale in order to reduce that tax burden.”

The same principle applies when it comes to your estate—but even more so. “You can roll assets over to a surviving spouse tax-free, but otherwise, everything is crystallized upon death,” Van Cauwenberghe explains. “You are deemed to have disposed of all your assets at fair market value when you die, and that can give rise to a big capital gains tax bill. On top of that, everything in your registered plans—RRSPs and RRIFs—must be included as fully taxable income in your final year’s tax return. In other words, your estate must pay the tax on whatever income you earned during your final year, plus tax on all of your registered assets, plus the capital gains tax, so the total bill can be huge.”

The box on the right provides a highly simplified example of how a large charitable donation can work to the benefit of your estate. The actual results depend on a number of variables, but the key point is that a large donation will generate a large tax credit, leaving more money for everyone (except the taxman). And if you also buy some life insurance, the policy’s tax-free proceeds can be used to offset the remainder of that tax bill.

“Life insurance can be used to cover any remaining tax liability, although it’s best to buy the insurance when you’re young,” Van Cauwenberghe advises. “The premiums will be much higher if you buy it when you’re older.”

Donor Advised Funds

There are a few further points to bear in mind when using this strategy. For example, your donations must be made to a registered charity to qualify for the beneficial tax treatment. You can refer to the Canada Revenue Agency website if you aren’t sure about a particular organization; the site has a list of all qualifying charities in Canada.

It may take some time to find the right charities, but here, too, you have options. “If you don’t know which to donate to, I recommend that you make your donation to a Donor Advised Fund [DAF],” Van Cauwenberghe says. “There are about 250 of these entities in Canada; Investors Group has one.

They’re like a parking lot for donations. You put money in and get the charitable-donation receipt, but you can’t get the money out. It must be used for charitable purposes, but you can decide over the next few years where you want to donate. A DAF takes the pressure off. You can make decisions about your donations later, once you have more clarity, and change your will to accommodate these decisions, or change the instructions in the DAF, or even ask family members to make the desired donations afterwards. You don’t have to make all these decisions at once.”

If you’re not sure about the effectiveness of a given charity (how much of its donations actually goes to the intended recipients), see below for organizations to which you can refer for detailed information.

“In any event, your priority should be to make sure that your estate plan is in order,” Van Cauwenberghe says. “You shouldn’t let the lack of clarity about your charitable intentions hold you up; you first need to decide on your estate plan—how much you want to leave for your beneficiaries, whether to buy life insurance, and so on— and you can use a DAF for the time being.

“You need to sit down with a financial planner and look at your estate and legacy goals holistically,” she adds. “There’s no right or wrong way to arrange things; it all depends on what you want to do. But you want to make sure that everything— your estate plan, your charitable intentions, and your overall financial plan— works together.”

Giving Through Your Estate

Federal and provincial tax rates as well as charitable-donation tax credit rates can be complex and vary from one jurisdiction to another; the following is an oversimplified example of how charity could be beneficial to your estate from a tax perspective. Actual results will depend on tax and credit rates as well as the amount of donations and the size of the estate, but let’s assume these parameters:

Finding High-Impact Charities

To avoid donating to a charity that actually delivers very little to would-be beneficiaries after its own expenses are met, you can do a bit of investigation before committing your funds.

Charity Intelligence Canada does a lot of investigation into the finances of Canadian charities and provides listings of those with the highest impact—that is, those that make the most effective use of donated funds.

Similar help is available on the Canadian National Christian Foundation website.