By Anne Gordon

The river, murky with silt, lapped gently against the causeway on our approach to Shingwedzi Rest Camp in the northern part of South Africa’s Kruger National Park. With five minutes to spare before curfew—visitors have to be in camp before dark—we stopped on the bridge to watch a tranquil scene of baboon domesticity.

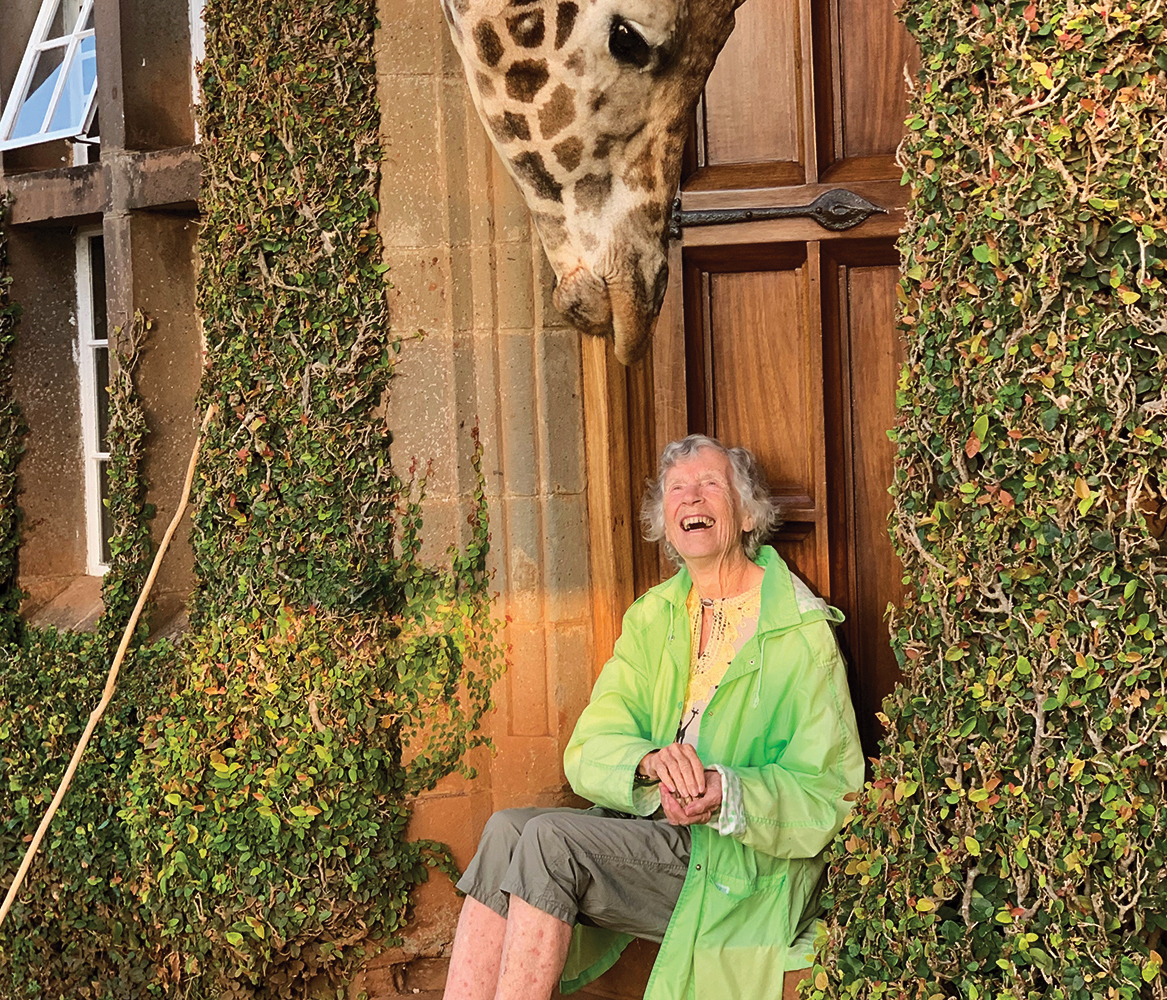

Giraffe, hippos, and caracal.

Photos: iStock/MHGallery (tree) and Mhgallery (hippo); Anne Gordon (giraffe and caracal).

On an overhanging rock, the dominant male, his back supported by a cushion of earth, stretched, his eyelids fluttering as he dozed in the warm light of early evening. Beside him, females with pink-faced babies clinging to hairy breasts groomed one another with long delicate fingers.

Covering 19,485 square kilometres (7,523 square miles) and spanning 360 kilometres (224 miles) from north to south, Kruger is not only one of the world’s most famous national parks but also one of the world’s richest wildlife habitats. With a population that includes just about every species of African animal, insect, reptile, and bird, there could hardly be a more compelling environmental experience.

Travelling through the park, you may see the white lions of Timbavati or maybe a Nile monitor, a large lizard, sunbathing on a rock beside a river. On a sandbar in the same river, there might be a herd of hippos lazing in the sun while close by a crocodile, motionless, ever watchful, waits for prey. Imagine surprising a herd of elephants, mothers holding rotund infants above the water’s surface with their trunks as they swim to the opposite bank.

Kruger has more than 20 camps, each with its unique attractions, connected by superb roads starting at Malelane in the south. Accommodation in the park is in rondavels (traditional circular thatched dwellings), permanent canvas tents (Hemingway style), bungalows, family cottages, and caravans ranging from rustic to deluxe.

At the centre of things is Skukuza Rest Camp, where luxurious lodges and rondavels are set in gardens landscaped with indigenous shrubs. Alongside Skukuza’s rondavels, sausage trees droop with the weight of plump fruit like oversized squash dangling from slender branches. For a more intimate experience, you can, as we did on one occasion, choose to bed down in a small bush camp, where amenities are minimal but adequate and the sound of hyenas or lions hunting in the darkness can seem to come from just outside your window.

A Million Diamonds

Oliphants Camp.

Photo: Anne Gordon.

Our first night in Shingwedzi was dominated by a gusty wind that rattled the windows of our rondavel. The lights flickered, dimmed for a second, and then spluttered out. Beyond our door, the African night vibrated with the shrill song of crickets and the stomach-rumbling “kwaak kwaak” of bullfrogs croaking their love song for the benefit of interested females. All around us the night throbbed with life.

Soon after dawn, we left the security of the camp and headed north to Pafuri Camp on the banks of the Limpopo River. Our route meandered through termite “villages” with their conical mud warrens, some more than two metres (six feet) tall. These bizarre structures are home to vast colonies of termites where a surprisingly sophisticated lifestyle plays out in a bustling metropolis of industry and procreation. The queen lays her eggs at an astonishing rate, while deep in the belly of the mound a bizarre form of agriculture is under way: a band of termites governed by instinct alone tend miniature fungus fields to feed the entire community.

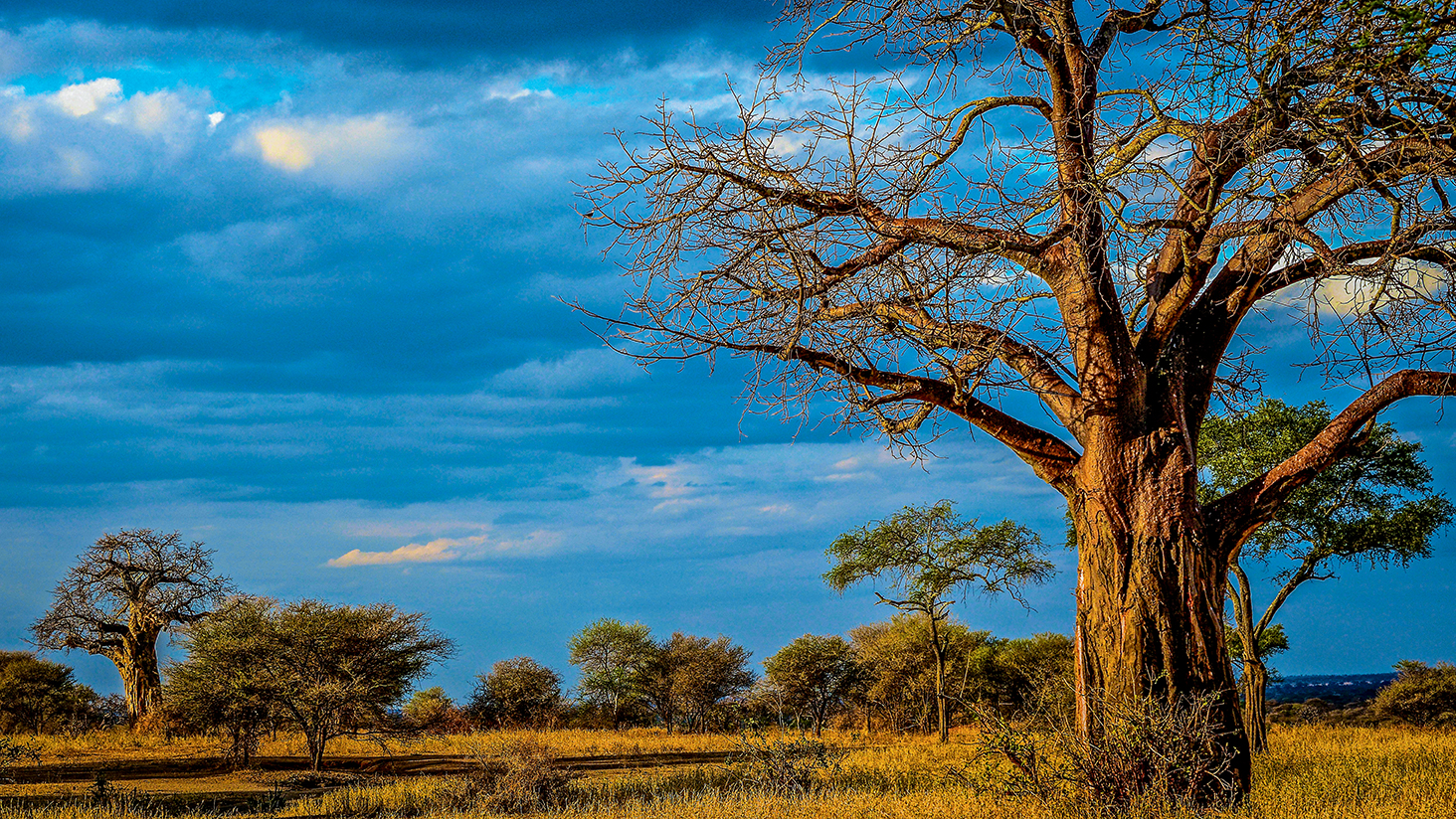

In these more isolated parts of the park, grotesque trees came into view. Standing majestic and strange among more conventional companions was the baobab tree. Evoking ancient times, some have been known to live for up to 3,000 years. Unlike the umbrella tree, with its low, flat widespread canopy, or the fever tree, with its lime-green bark, the baobab has a massive bulbous trunk, sometimes as many as 20 metres (66 feet) around, that sprouts truncated branches like stubby roots. In the Lowveld, a specimen was so huge that the gold miners working there in the last century used the hollowed-out trunk for a pub. The native people’s explanation for the tree’s odd shape: God in a fit of rage threw one down to earth and it landed wrong side up.

Olifants Rest Camp, where we spent our second night in the reserve, is built on the top of a cliff overlooking the Olifants River. As the Afrikaans name suggests, it has a huge roving elephant population.

As we watched from our rondavel, mourning doves dove and whirled overhead in a flash of grey. They swept by, returning at eye level, then dropped in a wide arc to the water below.

The first animals to arrive were, of course, the elephants. Plodding into the river, they trumpeted and splashed, shooting jets of spray from swaying trunks. Buffalo in the hundreds advanced close behind, stirring up dust clouds as they tramped towards the river in a heaving mass.

After dinner we made our way to benches perched high on the edge of the cliffs. The air was cool, with just a whisper of wind stirring the leaves around us. As we sat in the darkness, stars, like a million diamonds, trailed across an inky sky. Upriver we heard the grunt of a foraging hippo. From a fallen sycamore fig tree at the base of the cliff, the restless chatter of baboons filtered upwards as they jostled one another for the safest night perch. A solitary light from a bush camp twinkled mysteriously in the distance.

Not far from Olifants the following day, we left the main road for a rough sand track in search of an ancient baobab. We found it soon enough, and as we turned back, we found ourselves confronted by a herd of 15 browsing elephants. Our way was blocked and within minutes we were surrounded. A fair number of them were more than twice the height of our small rented car. They were so close that we could hear their tummies rumble and the contented snuffling of a baby elephant as it nuzzled its mother.

Unfazed, my husband, James, with many years of experience as a game warden in one of Africa’s premier game parks, assured me that we weren’t about to be trampled. “You wanted some close-up pictures,” he says. “Now’s your chance.”

Letaba Museum. Photo: SANParks.

After many elephant sightings, I had a modicum of courage, but this was eerie. At that moment all I wanted was out, but reassured by the quietly purring engine of our getaway car and the confidence of my personal escort, I snatched a picture or two, and then at my insistence, we scurried through the first gap that opened up as the huge animals continued their foraging. Alarmed by our hasty departure, the elephant nearest to us took fright and crashed off through the bush, trumpeting shrilly.

For those interested in seeing what is considered the finest as well as the most valuable collection of elephant tusks in the world, the Elephant Hall at Letaba Rest Camp has on display the ivories of the six biggest elephants in the history of the park (all died naturally). Gleaming and massive, the tusks each weigh more than 50 kilograms (110 pounds). Given such an enormous weight, it’s difficult to imagine how elephants hold their heads erect.

A Birdwatcher’s Paradise

Goliath heron, bateleur eagle, and lilac breasted roller.

Photos: SANParks (birds).

As a new day dawned, we were glad to see that Kruger is a haven not just for the Big Five—elephant, lion, leopard, buffalo, and rhinoceros. For both ornithologists and the casual birdwatcher, this game reserve is paradise.

Jewelled clouds of glossy starlings, their feathers gleaming with a blue-green iridescence, were the first camp visitors of the morning. As the sun rose, I sat quietly on the verandah of our rondavel, feet propped up on a wall, sipping fresh mango juice and writing in my journal. Suddenly, birds zoomed into the grassy courtyard and landed en masse on barbecue grates in front of the rondavels. Unperturbed by my presence, they squabbled noisily as they tussled with each other for scraps of steak and boerewors (farmer’s sausage) left over from the previous night.

Later in the day, we saw malachite kingfishers, fork-tailed drongos, lilac-breasted rollers, and a Bateleur eagle, its flight effortless as it caught thermals, lifting and gliding like a huge Chinese kite.

At one point, we stopped the car to check the map and a red-crested korhaan, or bustard, fluttered from the bush at the side of the road. It put on an Oscar-winning impersonation of a wounded creature with a broken wing to draw us away from its nest.

Later, when we stopped at a waterhole for a picnic lunch, a flock of squawking southern yellow-billed hornbills hovered over us in feverish anticipation of food scraps. As we watched them and they watched us, we ate traditional biltong—seasoned strips of sun-dried meat—and sipped ginger beer. The afternoon was hot and still.

A black-headed heron nearby tiptoed daintily in a murky puddle awaiting a silvery flash to galvanize it into action. In the long grass farther on, a secretary bird, claws extended, struck repeatedly at a snake in a death-dealing dance. There are more than 490 bird species in the park and we had already seen an astonishing variety.

The crowning glory of any day is a sighting of the one of the great cats—leopard, lion, and cheetah. We weren’t disappointed. In the dappled shade of a flat-crowned umbrella tree, a gathering of lionesses, one with three cubs hardly larger than domestic tabbies, feasted noisily on the carcass of a young zebra.

Above the kill, several vultures with a wingspan of at least two metres swooped and spiralled low, waiting for their turn at the leftovers. These birds have phenomenal eyesight. Gliding sometimes as high as 26,000 feet, the first that spots a kill and starts to descend draws others from miles around.

On this occasion, they had to compete with earlier arrivals—a family of jackals slinking around the site, a gathering of hyenas cackling in anticipation of a feast, and four large marabou storks hunched over like grumpy old men sitting together on a dead tree nearby—and the competition was fierce after the lionesses ambled off to rest in the shade. In a short frenzy of feeding, the scavengers reduced the once beautiful zebra to a backbone picked clean and a head, intact save for its eyes and tongue, soft delicacies for the carrion-eaters.

Snakes Alive

Closeup of Black Mamba snake with tounge out. Photo: iStock/Through-my-lens (snake).

On our last night in the park, we decided to treat ourselves. We wined and dined in Skukuza’s restaurant after being summoned to dinner by a waiter beating a thumping rhythm on a huge African drum. Our meal was venison with a bottle of South African Zonnebloem (sunflower) Pinotage. Before leaving, we sipped Amarula, a creamy liqueur made from the fruit of the marula tree. Like the elephants that sometimes become intoxicated after a feast on the overripe fruit of the marula, we, on the verge of intoxication and hopelessly lost, bumbled our way home. In the darkness, rondavels all look exactly alike.

As we giggled and tripped along overgrown paths like two teenagers, James tormented me with frequent warnings about the fat sluggish puff adders that lie around in the darkness waiting for a sandaled foot like mine to prod them into deadly action.

Before leaving the following morning, we sat with other visitors on an elevated patio overlooking the river where buffalo, antelope, giraffe, and kudu had come down to slake their thirst. A flock of doves fluttered to the river bank, drank hastily, and took off again. Close by, a tiny mongoose peered cautiously from the roots of a sausage tree, and then scampered across the mud to shelter beneath a rocky outcrop until the much larger creatures, satisfied, wandered off into the bush.

On our way to Numbi Gate, our exit from the park, we came across a two-metre long deadly black mamba wriggling on the smooth hot surface of the paved main road. Unable to gain traction, it struggled ineffectually to make the crossing. It was obvious that without help it would eventually exhaust itself and die.

Anyone familiar with African snakes knows that a mamba’s venom can kill. That didn’t deter James. He drove up alongside the reptile and put his hawthorn cane out of the car window against the snake’s body, providing a point of purchase for it to move forward. Repeating this several times, James was soon able to help it reach the rough earth bordering the road and slither silently into the bush.

Then and only then did we notice a line of cars behind us, the successful rescue having been watched by a fascinated audience.

Monkey, white lions of Timbavati, rhinoceros, and impala. Photos: Anne Gordon.