“My life’s ambition was to go to Africa,” says the celebrated scientist and author

By Peter Feniak

In her memoir, Dr. Anne Innis Dagg remembers her very young self and her first encounter with the world’s tallest creature in Chicago’s Brookfield Zoo:

“[We] stopped to admire the giraffe. I am not sure what thrilled me most—their great height, their long necks and legs, their large dark eyes, or all of these. I knew only that I was smitten. From then on, I wanted to know more and more about this wonderful creature.” (From Smitten by Giraffe, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016.)

She was three years old then, the youngest of four kids, on a trip with her mother to visit family. The year was 1936.

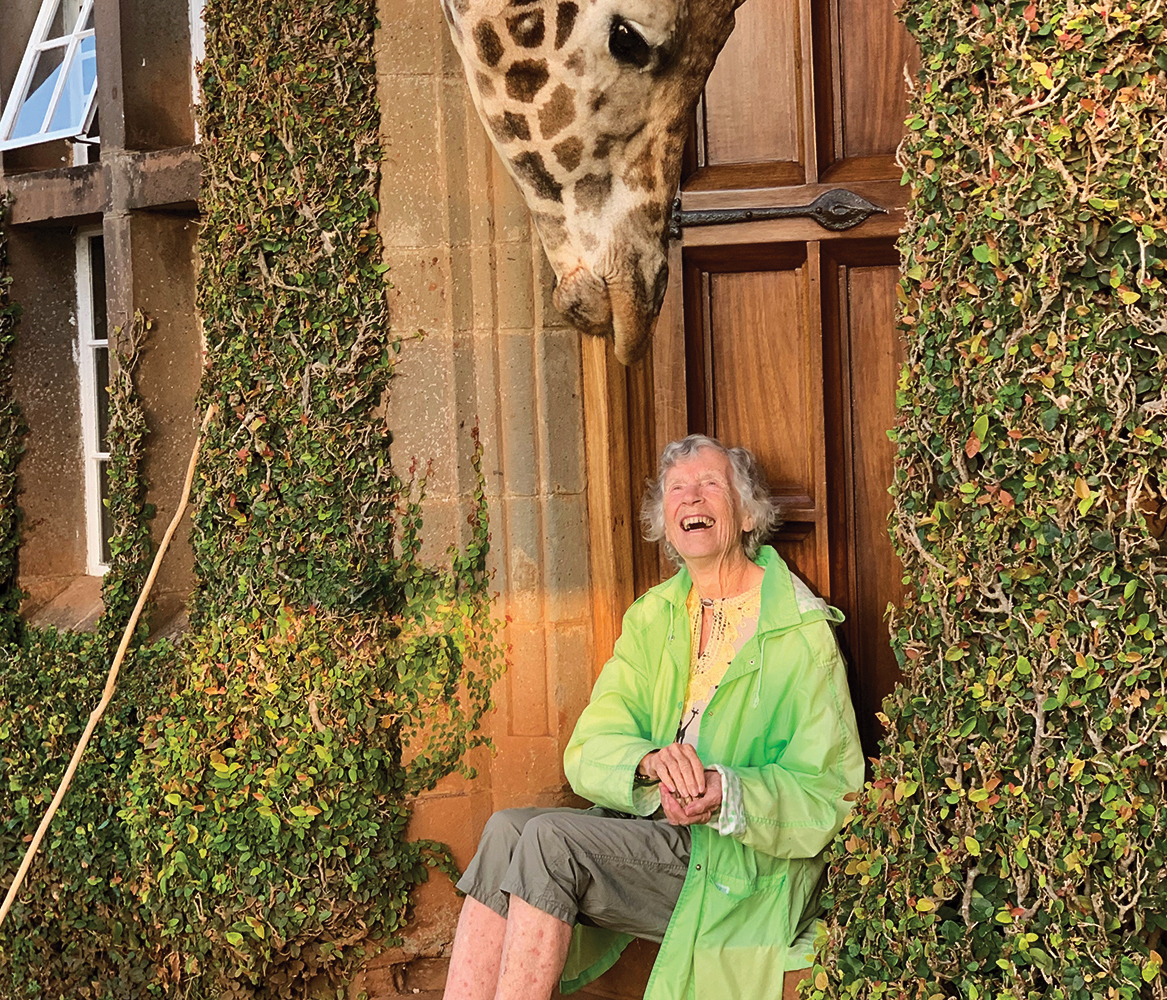

Today, as the feature documentary The Woman Who Loves Giraffes wins raves and awards, that Canadian girl is in her 80s and a suddenly celebrated scientist, feminist, and author whose life story—and deep knowledge of and love for the giraffe—is the heart of the film.

Still hale, Dagg had just returned from Kenya when we speak on a wintry afternoon from her home in Waterloo, ON. “It’s a lot warmer there,” she says. “We had a good time, but Canada’s good, too.”

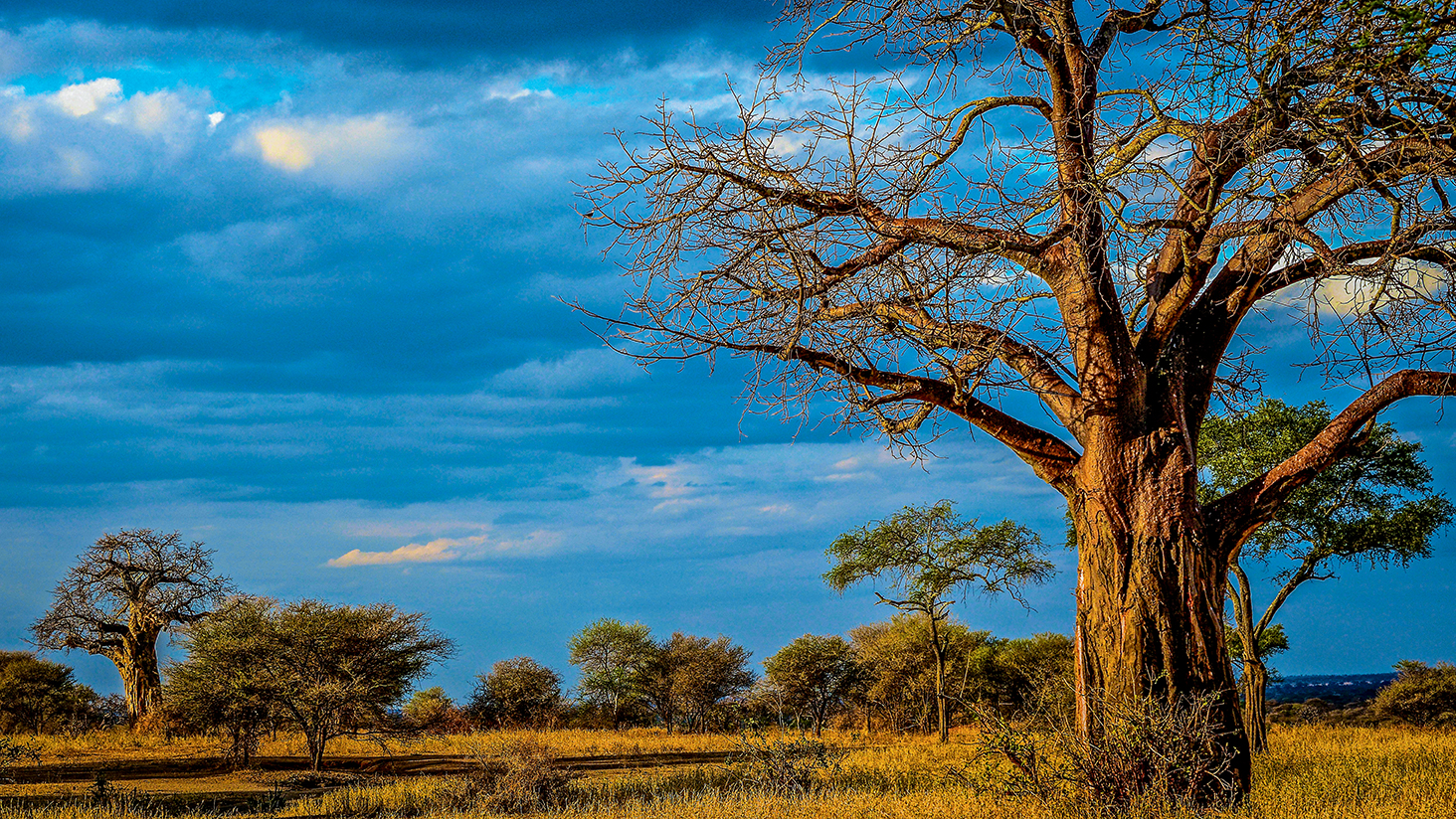

Conservation is always on her mind. Much of Africa’s wildlife is threatened, with the giraffe no exception. “Endangered? Oh, for sure,” she says. Giraffe habitat is challenged by population growth and climate change. The tall, graceful animals also fall victim to poachers and to “people killing giraffes just because their stomachs are hungry. And you can’t really deny them food. So, it’s tricky. But there are a lot of game preserves now, really spread out in parts of Africa, which is great.”

As more people screen or stream The Woman Who Loves Giraffes (it’s on Crave and iTunes), awareness grows about this special Canadian scientist. She grew up in a family of achievers. Her mother, Mary Quayle Innis, was a homemaker, historian, and author who later became the dean of women at University College, University of Toronto. Until his death in 1952, the same university was also home to Harold Innis, Dagg’s father, an economics theorist and one of Canada’s great thinkers. Toronto’s Innis College bears his name. His theories on media and communications inspired those of philosopher Marshall McLuhan.

“Maybe their habits just got into my system,” Dagg says. “The whole family was always busy. I think all four of us kids have written books, and of course my mother and father had, as well.”

Young Anne Innis formed a dream early and worked diligently towards it. “Growing up in Toronto,” she writes in Smitten by Giraffe, “my life’s ambition was to go to Africa and study the giraffe there. In 1956, when I was 23 years old, my dream came true.”

An Adventure

Today, that journey seems remarkable. Few women would travel alone back then, much less to spend a year in Africa. Dagg did, settling successfully in South Africa’s Transvaal Province to study the animal that fascinated her. Legendary scientists Jane Goodall (who studied chimpanzees in Tanzania) and Dian Fossey (who studied the mountain gorilla in Rwanda) would begin their work in Africa later in the decade. Dagg has called her Africa year “an adventure,” but she worked 10-plus-hour days closely observing and taking notes on giraffe behaviour, often sitting quietly near them in the front seat of her well-worn 1950 Ford Prefect. She marvelled at the strength of their necks—the males fight for dominance by striking each other neck-to-neck—and at the grace and power of their movement—a giraffe can gallop gracefully at speeds above 50 km/h (30 mph).

Sponsored by no one, she drew on her savings, what she calls “help from home,” and money from a prize she won studying biology at the University of Toronto. She had determination and enthusiasm, and the invaluable kindness of a ranch manager named Alexander Matthew.

She had written to everyone she could think of, seeking a place to study giraffes in Africa. Finally she found “Mr. Matthew” (as she would always call him), who agreed to house the student who shared his interest in local wildlife on the vast ranch (cattle and citrus were farmed) known as Fleur de Lys near South Africa’s Kruger National Park.

Dagg’s letter to Matthew had been signed simply, “A. Innis.” “He obviously thinks you’re a man,” Dagg’s mother told her. “Well, we can sort that out later,” Dagg replied. How it all worked out is part of the fun of the film.

The Woman Who Loves Giraffes came together in stages. Writer-director Alison Reid heard Dagg’s story on CBC Radio’s Ideas in 2011. “Then,” Reid says, “I read her book Pursuing Giraffe: A 1950s Adventure [Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2006] and envisioned what a fantastic film it would make.” The filmmaker and her subject would grow to be close friends.

“She’s extremely modest,” Reid says. “When I approached her about making this film, she said, ‘Why don’t we make a film about giraffes instead of about me?’ I had to convince her that a film about her story would be a friendly way into the giraffe conservation story. And that’s proven true—giraffe conservation organizations we list at the end of the film and on our website have benefited quite a lot. She was kind enough to give me the rights to her book and her life story.

“Then I found out she was going back to Africa for the first time in half a century. I asked if I could tag along and film her, and she said, ‘Yes.’ I filmed her over the course of five years. I started under my own steam. We didn’t have any financing.”

It took a team to bring Reid’s dream to life. She enlisted co-producers Paul Zimic and Joanne Jackson. Funding came from Ontario Creates, Telefilm Canada, Rogers, and Bell Canada. And as the film came together, Reid says, “I was finding out more and more layers of Anne’s story. There were some really happy coincidences that helped the story unfold.”

One charming discovery was footage from 1965 from the TV game show To Tell the Truth. As seen in the documentary, the show’s camera scans three young women. Then, legendary announcer Johnny Olson intones: “I, Anne Dagg, am a university lecturer in zoology and an expert on the giraffe. Panel, these ladies all claim to be Anne Dagg.” The game show’s celebrity panel then tosses questions, hoping to identify who is telling the truth. (“Are giraffes…monogamous?” asks comic Orson Bean, to much laughter. “No,” is the calm answer from the woman who knew.)

As the panel put their guesses on the record, music rises dramatically, until finally Olson booms, “Will the real Anne Dagg please stand up?” With a glorious smile, Contestant No. 3 stands. The Canadian had fooled everyone.

“It was really fun to do,” Dagg smiles today. “It was exciting. We [she and her late husband, University of Waterloo physics professor Ian Dagg] went down to New York on the train. We didn’t have a car at the time. It was all sort of new and interesting for us.”

Denied Tenure

After Africa, Dagg continued her work—earning a Ph.D. in zoology at the University of Waterloo, publishing research on animal behaviour, teaching as a university lecturer. But a career roadblock lay ahead—and it proved the great disappointment of her life. She writes in Smitten by Giraffe:

“All I needed to fulfill my dream of a life of teaching and doing research was to become a professor with tenure. What I had not counted on, however, was that at the time, universities were loath to hire women, no matter how experienced. In December 1971, after five years of teaching at [Guelph] University, I was denied tenure. I was devastated. I asked a member of the all-male committee if he had not been impressed with my list of research papers. He replied that it had not been made available to him. I was given no reason for the denial. I assumed that the department head did not want a woman with children who lived out of town to become a permanent faculty member.”

“There’s nothing not to love about Anne,” Alison Reid says. “She’s got a great sense of humour, laughs very, very easily. She’s incredibly kind, really easygoing—unless you’re hurting animals. She’s a very sensitive and a very feeling individual. The thing about her is, she wants things to be fair. And if there’s something she perceives as unfair, she’s driven to change things, to make things fair—like she did when she encountered the segregation of black workers in South Africa; like she did in the university world.”

Dagg walked away from university life. “My life became one not only of continuing to do research, usually at my own expense, but of fighting systems that discriminated against women,” she has written.

She would ultimately gather her groundbreaking work and that of fellow zoologist Bristol Foster to co-write with him the first scientific book on the animal she had long loved: The Giraffe: Its Biology, Behavior and Ecology (Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., 1976). That book came to be known worldwide as “The Bible on Giraffes.”

Dagg continued to research, write, and publish in other directions. Then, in early 1993, as her memoir tells, “my world fell apart.” Her beloved husband died of a heart attack after their weekly doubles tennis match.

She carried on, and the couple’s three children—Hugh, Ian, and Mary—grew into lives of their own. Meanwhile, in the scientific world, a community grew that Dagg knew little about. It comprised scientists like her, passionate about the study and conservation of the giraffe, who began to ask, “Where’s Anne?” Dagg’s moving welcome by and re-entry into that community of “giraffologists” is a high point of The Woman Who Loves Giraffes.

As Reid’s work progressed, she continued to discover new layers of the story she wanted to film.

“Anne’s a trusting person,” she says, “and she was very open with me. She gave me total access to all her personal letters.” In the film, acclaimed Canadian actors Victor Garber and Tatiana Maslany bring the voices of Dagg, her mother, Mary, and Mr. Matthew to life as they read letters to and from the Fleur de Lys ranch.

“There are so many beautiful parts of those letters,” Reid says. “I wish I could have used more of them in the film. In one of them, Mr. Matthew writes to Anne’s mom with something like, ‘I just want you to know: Your daughter is just an amazing person. I’ve never met anyone like her.’ And Mary Quayle writes back that she’s worried whether Anne has enough money, but adds, ‘You know Anne—when she makes up her mind, she’s going to stick to it.’ It’s just interesting to see the banter back and forth.”

Another wonderful treasure for the film came as Reid found, stored in Dagg’s home, film canisters containing amazingly well-preserved footage. In Africa, Mr. Matthew—an avid amateur with a Bolex 16-mm camera—had filmed giraffes in the wild. He also captured the scientist at work in her small car and relaxing at Fleur de Lys. Suddenly, 1956 comes to life onscreen.

The vast ranch is gone now. The property is subdivided and paved roads run through it, and the ranch house is now a bed and breakfast. There are still giraffes nearby, but fewer. To see it as it was then and now is truly special.

Among those who love the film are Mr. Matthew’s three granddaughters, who have attended several screenings. “They all live in California,” Reid says. “It’s been great to connect with them. And they are, of course, very moved to see their grandfather in the film.”

“I think they’ve missed their grandfather a lot,” Dagg says.

Dagg continues an active life, whether travelling for film screenings or at home at her computer, e-mailing “with people I’ve been connected with for years on animals of some sort.” She continues writing and research. Athletic all her life, she “was told about 15 years ago I had to give up tennis—but walking and riding my bike in the summertime, I can do without any problem.” As 2019 ended, word came that she had been appointed to the Order of Canada.

Giraffes are still prominent in North American zoos and wildlife parks. Dagg, always an advocate for animals, accepts the reality of giraffes in captivity:

“I think they’re used to it and I think they’d be more frightened if they were sent on a boat back to Africa. Some have lost their lives in doing that. I think you might as well go ahead with what’s here and do your best. They’re very adaptable. I think they can manage.”

The pioneering Canadian scientist has now seen The Woman Who Loves Giraffes many times. She never tires of it. “Each time I see it, I see something a little bit different. And I get to thinking what it was like and I quite enjoy it.”

She’s still dazzled by the remarkable animals. She marvels, “Its height just really strikes you [giraffes can grow to be 19 feet tall, with necks as long as seven feet], as does its look of interest—a gentle animal even though it is so large.”

Of her great scientific adventure of 1956, she says, “I can remember exactly what I was doing. It was so important to me at the time. I was in euphoria the whole year. It was just so wonderful to look at your favourite animals and make notes. Week after week, it was fantastic.”

To learn more and see the official trailer of the film, visit thewomanwholovesgiraffes.com.