By Rob Lutes

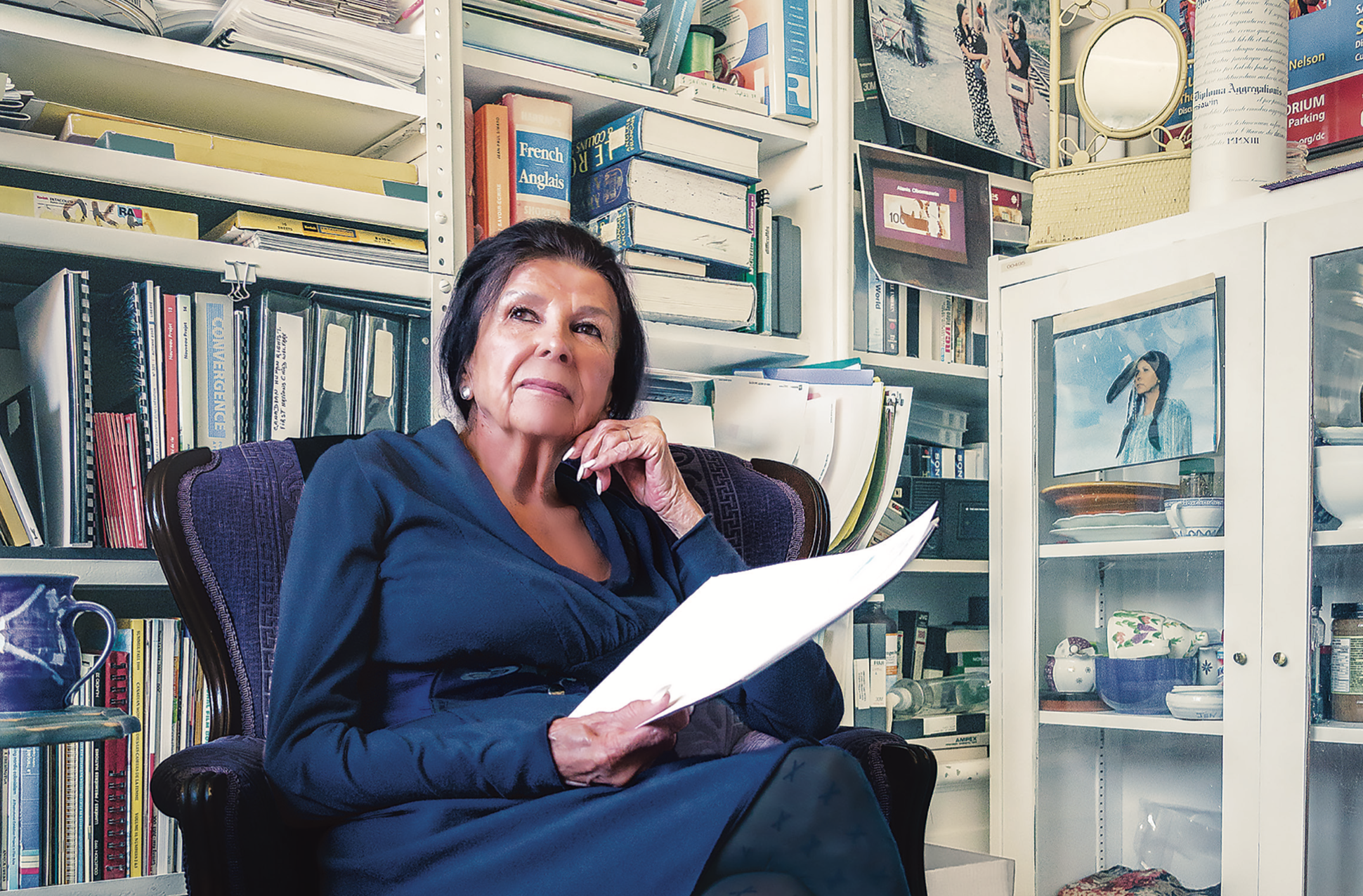

For more than 50 years, renowned Abenaki filmmaker and activist Alanis Obomsawin has chronicled the stories of Indigenous Canadians

Alanis Obomsawin is one Canada’s foremost documentary filmmakers and among the world’s most important Indigenous artists and activists. Her extraordinary body of work—54 films and counting—reflects her commitment to the well-being and preservation of the cultural heritage of Canada’s Indigenous peoples.

Born in Lebanon, N.H., Obomsawin was raised in Odanak, an Abenaki First Nations reserve northeast of Montreal. She came to filmmaking through her career as a storyteller and singer, work that brought her into schools, prisons, and performance venues throughout the 1960s sharing the stories and songs of the Abenaki people that she had learned as a child. Obomsawin is also a celebrated visual artist, known for her engravings and prints.

Hired by the National Film Board of Canada as a consultant in 1967, she made her directorial debut in 1971 with the animated documentary Christmas at Moose Factory, which features drawings and stories by Cree children at a residential school in Northern Ontario. It marked the beginning of an exceptional career that has included many landmark films, most notably Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993), a devastating look at the armed standoff between Mohawk protesters, the Quebec police, and the Canadian Army during the Oka Crisis in 1990.

An officer of the Order of Canada, Obomsawin has received numerous awards and honours, both in Canada and internationally. Her work was featured in early 2022 in a special retrospective, “The Children Have to Hear Another Story—Alanis Obomsawin,” at Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt (House of the World’s Cultures). The exhibit will be at the Vancouver Art Gallery in the spring of 2023 and at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto in the fall. Now 90, Obomsawin is currently working on several films.

Can you describe your upbringing?

I was born in New Hampshire. We moved to Odanak, where my parents came from, when I was six months old. Later, we moved to Three Rivers [Trois-Rivières, Que.]. I must have been five or six. We were the only Indians living there. I went to school and it was pretty horrible, a lot of beatings and racist stuff going on. By the time I was 12, my father had passed away and I was very disturbed. And I told myself “Nobody is going to beat me up anymore.” So I really revolted against this kind of stuff, and I managed to defend myself. Life was difficult.

What kinds of treatment did you face?

Children would run after me and knock me down and kick me. Over the years, I realized that children are not born racists. I just felt that they had heard another story about us because the books they used for teaching were so bad, especially on the history of Canada. We were savages and went around scalping people. So no wonder they hated me.

But your work has brought real stories of Indigenous Canadians to light.

Yeah, and I guess this is why I’m still here. I’ve seen a lot of changes and a lot of progress in this country concerning our people. It’s very encouraging. I’m glad I’ve lived this long to see the difference. Now, books are being written by our own people across the country and lots of films and other material are being made. Therefore, whenever I do something, I’m thinking of education. I want the films to be used at universities, high schools—all levels.

You’re known as a filmmaker, but you worked before that as a storyteller and singer.

That comes from where I come from. Storytelling is part of everyday life. And I thought that the children had to hear a different story. So that’s how I started, first with the Scouts—travelling with them, singing songs and telling them stories from our people. And then eventually I started being invited into classrooms; I did presentations at hundreds of schools across Canada and some in the States. I did a lot of research. This was in the early ’60s. And I became known as a singer, really.

What sort of material did you perform?

Everything. I sang a lot of traditional songs, and I wrote some of my own. And for nine years, beginning in the 1960s, I ran an Indigenous stage at the Mariposa Folk Festival [in Orillia, Ont.]. It was for Indigenous artists like Willie Dunn and others. A lot of people came to be part of that stage.

How did you come to make films?

In the early ’60s, I did a campaign to build a swimming pool in my community of Odanak because our children were not welcome in the swimming pool of the neighbouring community. They had a pool, but they didn’t accept our children. So I told them, “Don’t worry; we’ll have our own pool.” I thought it would be easy, but I’m telling you it was hell to get it done. But I did.

That involved raising money?

Yes. The pool is still there—they’ve taken very good care of it. And a lot of young people became lifeguards. It was very helpful. And a couple of years ago, people from that same town that hadn’t our children came to us because they don’t have a pool anymore. And they asked if their children could come to swim at our pool. And, of course, our people said yes. And I was very much in favour of that, too. Filmmaker Ron Kelly made a film on that campaign for CBC, and it appeared on a prime-time program called Telescope. People at the National Film Board of Canada saw it and invited me to come to meet with the directors and producers. That’s how it started. I started making my first film, Christmas at Moose Factory, in 1968. It came out in ’71. And it’s still quite popular.

It’s a beautiful film, with the children of Moose Factory telling you their stories.

I went there and I would live with the children in the dorm at the school and go to the classroom every day and tell them stories. They knew me very well. I was there for three years in a row. Once they were comfortable with me, I said, “I’ve told you so many stories; now it’s your turn to tell me stories.” I was very familiar to them; that’s why they were so comfortable.

The comfort level is present in all your films. How does that come about, and how important is that?

It’s very important. Before I start filming, before I start coming with the crew, I go alone and I interview people and get to know them. Until I really understand what the story is, I don’t come in with the crew. That’s how they can trust me.

Your film Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance was quite different.

Yes. In this case, it was like guerrilla filmmaking. I spent 78 days behind the lines alone or with a small crew filming what was happening. I did the interviews after. I talked to people whom I had seen there and who I knew were going to be in the film. I wanted to see another side of it.

How did that film affect your life?

Many people really hated me because I made that film. It was very difficult.

Your most recent film, Bill Reid Remembers (2022), is a beautiful view into the mind of an artist. How did it come about?

Because of the pandemic, we’d been working at home a lot, and I started listening to some of my archives. I was so touched by them that I cried all day And I just felt that I had to do something about some of these stories. I had forgotten that I had interviewed Bill in 1987. His was one of these stories, and that’s how this film happened.

During the pandemic, you released a powerful film, Honour to Senator Murray Sinclair (2021), the former Canadian senator who was chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

I had heard that he was going to receive an award for his work, so I called him and asked if he’d allow me to film the ceremony at McGill University. I think that film is an important document in terms of really understanding the situation of the residential schools. His speech is just incredible. I think every word he says is sacred; you’re learning something of that history.

The film includes some raw testimonials from survivors. How important was that commission’s work?

I think it’s so important—not only the commission but all the books that they’ve come out with in French and in English, all the information. It’s the unbelievable realization of that history; it’s extraordinary. And what it did to our people who were hiding these stories and didn’t want anybody else to know. All of a sudden, all those people felt a lot of healing because of speaking and being appreciated by everybody in general.

As a filmmaker, you’ve been remarkably prolific.

I’ve made 54 films so far, and I’m working on quite a few more. I think in a few months, it will be 60!

You turned 90 in 2022. A lot of people have would have retired by this point.

I don’t have time to retire. There is still much work to be done. I love what I do. Everybody is important; it doesn’t matter who they are. I want to help get these stories out.

So what would you say to older people about their own stories and creativity as they age?

A lot of people are worried about getting old. I’m not. I cherish every day. I feel lucky. I can walk. I can talk. I can do all kinds of things. I have life and it’s very sacred. It doesn’t matter how old you are; there’s something that you’re learning all the time.

And what does Alanis Obomsawin do to relax?

I work.

And when you’re not working?

I think. I’m always busy in my mind and in my heart. I appreciate people. And I’m there to tell our people how beautiful they are. And they don’t know it. And I keep telling them.

Photo: National Film Board of Canada