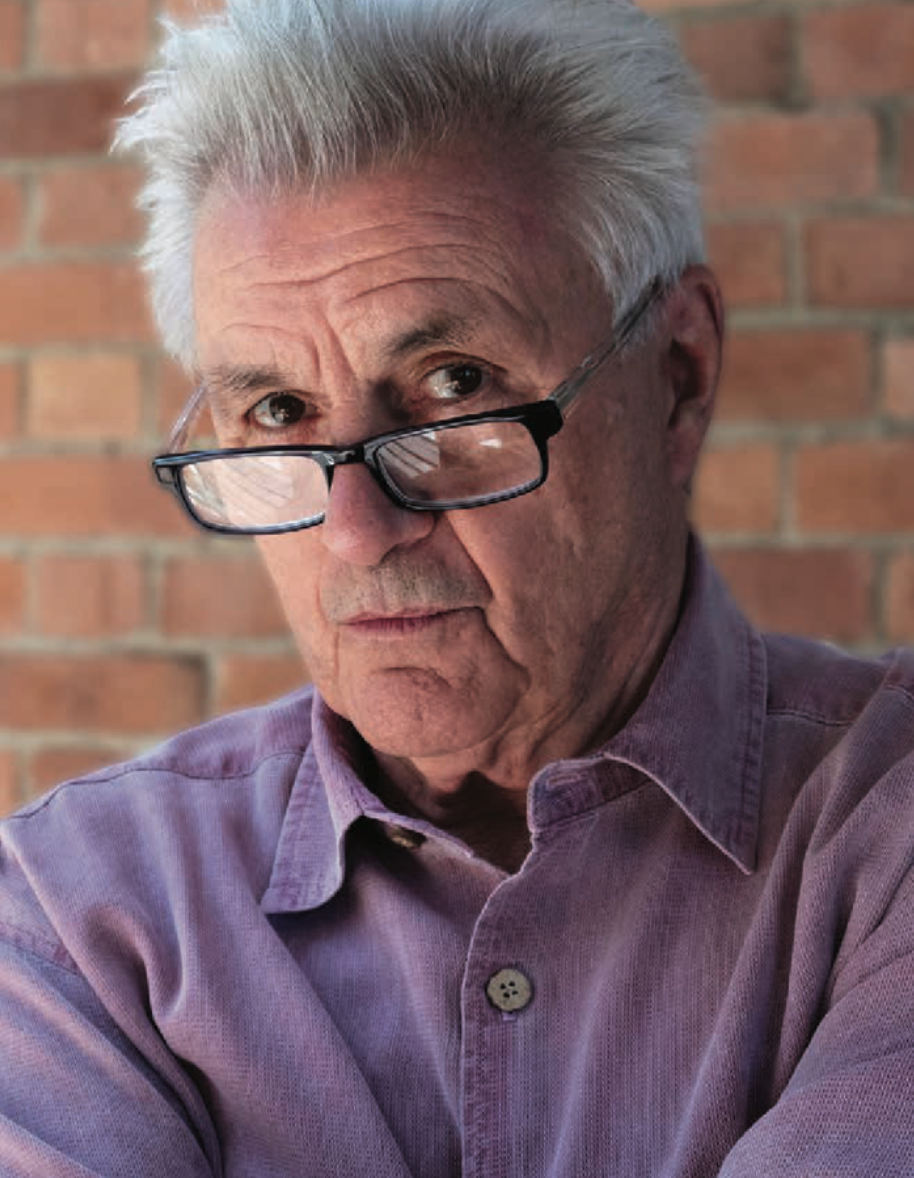

With his latest book just out, the celebrated Canadian-American author looks back on his life and career

By Peter Feniak

By 1978, John Irving—age 36, married with two young sons and working two jobs—had scrimped enough time to write three novels. They were well reviewed but little read.

A fourth novel changed everything. Irving’s The World According to Garp became a sensation. A creative wonder, it follows nurse Jenny Fields—a fierce, driven, unmarried single mother—as she and her son, T.S. Garp, grow through years of triumph, distress, imperfection, and complex sexuality.

Book reviews dazzled: “full of energy and art, at once funny and horrifying and heartbreaking” (Washington Post); “brilliant, funny, and consistently wise, a work of vast talent” (The New Republic). Garp wasn’t for everybody, but it would sell millions of copies. It won America’s prestigious National Book Award and was translated into more than 40 languages. And it was adapted for a Hollywood movie, starring Glenn Close and Robin Williams. By the time Irving was on the cover of Time Magazine in 1981, almost everyone seemed to know his name.

In November 2025, Queen Esther (Knopf Canada), Irving’s 16th novel, arrived in bookstores. His vast readership would recognize its epic scope, colourful characters, and captivating tone. His new novel revisits St. Cloud’s, Maine, orphanage central to The Cider House Rules, and includes familiar Irving motifs: Victorian novels, Vienna, a rich, time-spanning plot. The book’s cover shows little Esther as she arrives alone at the orphanage on a snowy night in 1909.

Esther is a Jewish orphan—her father having died during their journey from Europe, her mother murdered in America in an anti-Semitic attack. She isn’t adopted until she’s 14. Welcomed by the Winslows, an openminded family in a narrow-minded New Hampshire town, Esther grows to womanhood and thanks her family by birthing a son for Helen, the unmarried youngest daughter. She departs for Europe seeking her roots.

The novel then follows “Helen’s son,” Jimmy. “An exaggeration of myself,” Irving says.

A Book That Changed a Life

“The latest John Irving novel” is not a concept the author would have envisioned in his young years.

Speaking from his office in midtown Toronto, he recalls his teenage frustrations. “I didn’t start writing at age 15,” he says. “I was struggling not to flunk out of school [Exeter Academy in New Hampshire]. I was a slow reader [he was diagnosed dyslexic]. What had I written? I never kept a diary. I never wrote about me.”

But his mother, Helen Irving, would often bring him to the local theatre, where she was a prompter. “I was always trying to make up a story,” he says. Then he read Great Expectations. Can a book change a life? Irving knows it can.

“Because of that novel, I not only wanted to be a novelist—I wanted to be a novelist only if I could write like Charles Dickens.” He was dazzled by Dickens’ rich work: “the characters, the plot, the social conscience, the humour, the sadness.”

How would he begin? His stepfather, Colin Irving, a teacher at Exeter Academy, “was instrumental,” he says. “He knew what I liked to read. He said, ‘Well, if you like Dickens, and you like Melville, you might like Dostoevsky, too. Flaubert, Balzac…he’d read everything.” (Irving never met John Blunt, his biological father.)

As his dream of writing began to take form, Irving was surprised by a proposal for his progress from his brisk New England mother. “I came from an outdoorsy kind of family,” he says.

“In New Hampshire, everybody was a skier. My mother was an expert. Truth be told, I wasn’t really crazy about skiing. I never really liked sports. I hated Little League baseball. I was small. Football, basketball, hockey were not for somebody small. It was a coincidence that my parents were close friends with the wrestling coach at school. And one day, my mother took me to a wrestling match. She said: ‘This is what you should do. It’s a weight-class sport. You wrestle somebody who is your size, your weight. You are small. People pick on you. You get in a lot of fights. Wouldn’t you like to win one?’ And I thought, ‘Really?’”

Wrestling coach Ted Seabrooke declared young Irving’s athleticism “halfway decent” but added that “talent isn’t everything.” Winning the intense bouts on the mats of America’s popular Collegiate Wrestling demands discipline, strategy, and determination. Irving took the challenge. Having grown to a muscular five-foot-eight, he graduated as captain of his school’s wrestling team. He went on to wrestle competitively until age 34—including at the universities of Pittsburgh and New Hampshire.

He coached wrestling until he was 47. Wrestling appears often in his novels. In 1992, for honouring the sport, Irving was inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame in Stillwater, Okla.

His First Reader

Irving’s determination also honed his writer’s craft. He broadened his experience overseas in 1963 with a year’s study in Vienna, Austria. He created short stories, and a few of them were published. In 1965, he was admitted to the prestigious Iowa Writer’s Workshop at the University of Iowa. His Master of Fine Arts thesis became his first novel, Setting Free the Bears, in 1968. And at university, he found an inspiring friend.

“I had the good luck of having Kurt Vonnegut as my teacher and mentor and the first reader of my first novel,” he says. “It was a historical novel, set in Vienna at the time of the [Nazi] occupation. It was a good novel to be showing Vonnegut, a former POW in Dresden. We were kind of well matched. At the time, he was writing Slaughterhouse Five. The reaction to his comic novel about the firebombing of Dresden was, as you might imagine, mixed. It was educative to me to see how Kurt handled that.” Slaughterhouse Five became an American classic.

The tsunami that was Garp eventually receded, but over the following years, Irving would take his place among the masters of fiction. Readers embraced his carefully crafted novels, Hotel New Hampshire, The Cider House Rules, A Prayer for Owen Meany, and A Widow for One Year among them—all four bestsellers.

His storytelling is full of warmth and sentimentality, alarm and dread, colourful characters, and richly framed history. Adapted for film, The Cider House Rules was nominated for seven Academy Awards in 2000, including Best Picture and Best Director. Michael Caine won for Best Supporting Actor as Dr. Wilbur Larch.

Irving, who had long resisted writing for movies, was the Oscar winner for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Empathy

Like most Irving novels, Queen Esther is set in the past. “I don’t want to write about the present,” he says bluntly. “I don’t have any perspective on the present. I’m a very slow writer. I take notes, I build a timeline, build a cast of characters. They wait. They wait a long time before I know enough about how it ends to know where I should begin. I never begin until I know everything I need to know about the ending. It’s simple—but it’s slow.”

Social conscience often shines in the celebrated novels of Dickens as he exposes Victorian poverty, corruption, child exploitation, and cruel class barriers. Irving, too, often writes with a social purpose, addressing subjects such as freedom of choice, family values, LGBTQ rights, and the war in Vietnam. Queen Esther ponders anti-Semitism.

“Esther has been denied the Jewish childhood she should have had,” Irving says. “Anti-Semitism has taken it away.” He named her for Queen Esther of Persia, who hid her Jewish identity and then stepped forward to save her people from annihilation (as told in the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament). Irving’s Esther finds her heritage and joins the struggle for an independent Israel.

“What I wanted to do,” he says plainly, “was to make the reader feel empathy for one of those Jews who became one of the original Zionists. Her Jewishness, when she reveals it—watch out.” Irving’s story ends in 1981, but crisis and heartbreak continue in the Middle East—Queen Esther might be a difficult book to launch. “I don’t doubt it,” Irving says. “I don’t doubt it.”

A Writer All Day

In the early 1980s, a newly divorced Irving found his life changing. He met Janet Turnbull, a Canadian literary agent and publisher of his books in Canada. Irving began to cross the border often. At the wedding in 1987, their friend Robertson Davies read a biblical passage. Irving’s sons, Colin and Brennan, were his groomsmen.

For a time, the couple had homes in both Vermont and Ontario. Over the years, that changed. Their creative daughter, Eva Everett Irving, now works in the United States. Irving himself now lives year-round in Canada, with homes at picturesque Pointe au Baril on Georgian Bay and in busy Toronto. He became a Canadian citizen in 2019. A dual citizen, he has made it clear that he stands “as a Canadian” in the current strife with the United States.

“I’ve already started the 17th novel,” says Irving, now 83 years of age and embraced as one of the great authors of our time. In his deliberate, thoughtful way, he looks back: “I feel very lucky that I got to do the only thing I wanted to do full time. Writing those first four novels, I had two full-time jobs. I was coaching wrestling, and I was teaching English. I thought I always would be. If I got to write two hours a day, not every day, that was about it. And I had two young children. Well, I didn’t dislike teaching English—I liked my students. I didn’t dislike coaching wrestling—I knew wrestling. But I wanted to be a writer all day, every day.

“So when it did happen, when I had a bestseller, everyone was reading me, and I could envision getting to write seven days a week, all day, which was always my dream, I didn’t quite believe it. I thought, ‘Eh, we’ll see; we’ll see how long this lasts.’ It did last. And from that moment it has felt like…a luxury not a burden. That’s all. I just feel… it worked out.”