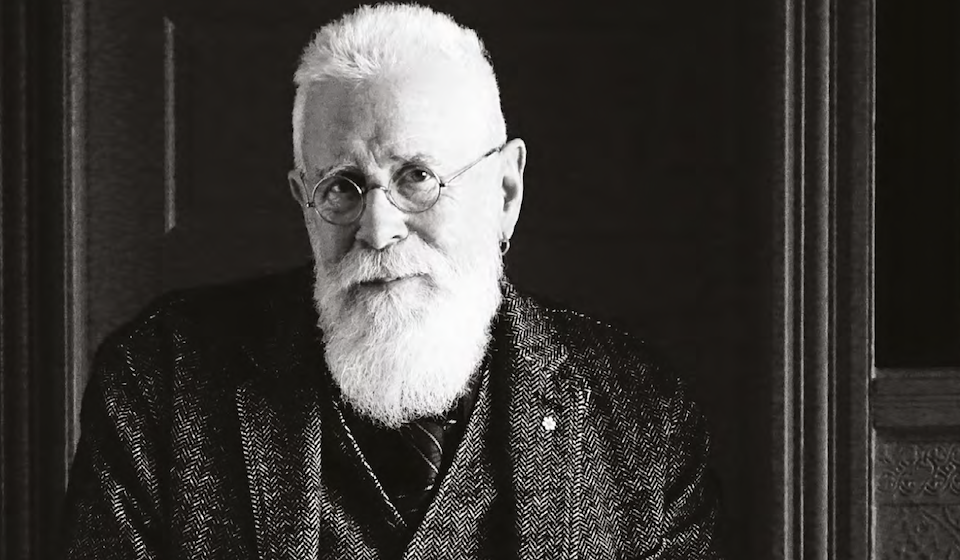

By Rob Lutes

One of Canada’s finest songwriters and performers reflects on some of the origins and inspirations that have shaped his illustrious career

Where did you grow up?

I was born in Ottawa, and I lived there until I went to music school in Boston [the Berklee School of Music] at the end of high school.

Did your love of music come from your family?

It did in a way. I think my dad felt that he had to expose his new son to the best in culture. So he subscribed to the Book of the Month club and a record-of-the- month club when I was three or four. Every month a classical album would come in the mail, and we’d sit in the living room and listen to it. Some of it was powerful, and some of it was hor- rible—to a toddler, I mean. So that kind of set the stage. And Mom and Dad used to sing in the car. When my brothers and I got old enough to be critical of that, they stopped doing it. But both of them also played piano.

When did you first learn to play an instrument?

Around about Grade 5. My dad’s brother had a clarinet no one was using, so I ended up taking a year of lessons on it. I liked the lessons, but I wasn’t excited about the instrument, so I switched to trumpet. When I got to high school, I ended up having to start over again with Grade 9 kids who had never touched the trumpet before, and it was really boring. So I dropped music. I was 13 and I’d had my fill. But I’d been listening to rock ’n’ roll. In the same way that my 12-year-old daughter gets excited about Taylor Swift, I was excited about Elvis Presley. Then I discovered this beat-up old guitar in my grandmother’s attic and that was the end of the beginning—or the beginning of the end, depending….

You’re known as a masterful guitarist, and it seems that you’ve continued expanding your skills over your career.

I think when you stop learning, it’s over. The pace at which I learn is much slower than it was when I was starting out. When you’re young, everything goes in there. Most of what I do now is the result of that. But I’m still learning. Having developed a bit of arthritis in my hands, I’ve had to reinvent the guitar parts for certain songs, so that itself is a learning process.

You’re widely known as a folksinger/ songwriter, but when you were starting out, you were a rocker.

I’m not sure how much I rocked, but, yeah, I was. My parents weren’t fans of Elvis or anything that rock ’n’ roll repre- sented, so they said, ‘We’re okay with you playing guitar, but you have to promise two things: you’ll take lessons, and you won’t grow sideburns and get a leather jacket.’ I was 14, so those were easy commitments to make. And the lesson thing was great. I learned a lot of stuff fast, much more sophisticated chordal concepts, and I was introduced to jazz.

You brought a kind of jazz sensibility to several Ottawa and Toronto bands over the 1960s, but when you recorded your first album in 1969, it was folk.

I played in a few bands over those years, but over time my intention became to get out of bands. I had these songs that I liked better when I played them myself. There was a band, Kensington Market—Gene Martynec was playing guitar with them. After they folded, Gene and I ran into each other in a café in Yorkville in Toronto. He wanted to get into record production, and I wanted to make a record— like a Mississippi John Hurt record, just me and the guitar. And Bernie Finkelstein, who had managed Kensington Market, was trying to set up a record company. So we all got together, and that was the first True North album.

How did that change your career?

I was so naive about it. The day the album came out, I happened to be walking around Yorkville, going in and out of shops. FM radio was new, and CHUM-FM was playing in every store. They played my whole album. It freaked me right out. I thought, “I’m never going to have privacy again.” But it was Bernie’s strategic ability that got the record moving, and then he started managing me, and it took off from there.

When you write songs, are you writing for yourself or for your audience?

I can’t really separate those elements. The songs are a product of my own emotional response to things I encounter, whether they’re personal things or larger-scale things. People who have embraced my stuff don’t do it because they’re in love with me; they embrace the songs because the songs speak for them in some way. If I stick to my own personal truth, it’s bound to be accessible to other people in terms of their own personal truth.

What are your guiding principles when you go onstage?

When I walk out onstage, I’m saying to myself, “Don’t screw this up.” But after this many years, you know you’re not going to do that. I never know that. I don’t screw it up very often, but once in a while. But I don’t take it for granted. I think that what I feel when I’m with an audience is love. I didn’t understand this at all in the beginning. It was just a compul- sion—I’ve got these songs I want to play so people can hear them. But over time, I came to understand that it’s about love.

You’ve toured internationally for years, and you now live in the United States. Has your perspective on Canada changed?

I don’t think it’s radically changed. But I do remember saying to an audience in Yellowknife a few years ago that we are at the top of Canada, more or less, looking down. You look south from there, and you kind of see all the way to Tierra del Fuego at the bottom of Argentina, and it’s like sanity stops at the Canadian border and south of that it gets progressively nuttier. Canada is always teetering on the brink of getting too much influenced by American stuff. But we have maintained this kind of separate identity, and this identity is worth preserving.

Your latest album, O Sun, O Moon, has received rave reviews.

The songs, as always, unfolded over time. Songs are always gifts. Some- times the gift comes in need of a lot of unwrapping, and other times it’s just right there on a platter. And there are several of those on this album, like “Into the Now” and “Push Comes to Shove.”

“Push Comes to Shove” sounds as if it could be about love between people or a love of God.

Love is love is what I have come to feel. And the love between people, we clut- ter it up with all kinds of crap. But if you don’t do that, or if you can get down to the essence of it, it’s also sacred.

As you age [Cockburn turned 79 on May 27], is there anything you’ve learned that you would share with others entering their later years?

I don’t know if I have any really pithy advice, but I think that if you want to keep moving forward in life, you have to stay open to other people’s ideas, to other people’s feelings, to criticism of yourself. And that doesn’t rule out greater confidence. I feel more confident than I ever have. But it’s not 100 per cent. And it shouldn’t be, because I’m wrong about some things. It’s one thing to become more comfortable knowing what you want, but what you don’t want is to have aspects of yourself become encrusted with habit and become entrenched. And we are all going to be dealing with physical problems; unless you become incapacitated completely in some way, the aches and pains that you have to live with shouldn’t be as much of an issue as who you are and where you are in relation to the divine, where you are in relation to the cosmos and to your fellow human beings. That’s what’s important.