It’s the most prolific killer you’ve never heard of—and the lethal weapon it uses to attack is your own body’s immune system

By Wendy Haaf

Photo: iStock/Squaredpixels.

One day, Shirley Hill of Chatham, ON, then 61, was undergoing a routine outpatient procedure to break up a kidney stone; the next day, she was in the intensive care unit, fighting for her life.

Rhea Copeland’s life-threatening battle began after routine surgery to fix a failed hernia repair, but the Thornhill, ON, woman remembers nothing between closing her eyes in the O.R. and awakening in the ICU six weeks later with countless tubes sprouting from her body.

Each year, more than 30,500 similar life-and-death dramas featuring the same villain unfold in Canada (outside of Quebec, for which figures aren’t available), and the precipitating incident can be something as seemingly innocuous as getting nicked with an improperly sterilized implement during a pedicure or a mosquito bite that’s been scratched raw. When someone dies supposedly of the flu, H1N1, pneumonia, an overwhelming overgrowth of yeast following chemotherapy, or virtually any other kind of infection, the real culprit is usually sepsis.

Probably the most prolific killer you’ve never heard of, sepsis is the second-leading cause of death in hospital, and it disproportionately affects people over 60. In fact, the risk rises roughly 10 per cent each decade after age 50. About half as common as heart attack but at least twice as deadly (with a mortality rate of about 30 per cent), sepsis has probably ended the lives of several people you know, and yet this diagnosis probably doesn’t appear on their death certificates. What’s more, many of those who survive an encounter with this attacker are marked for life, left with lingering after-effects such as fatigue, muscle weakness, pain, and decreased cognitive function.

“About 50 per cent of survivors over age 66 can’t take a shower on their own,” notes Dr. Claudia Chimisso dos Santos, a researcher funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and a clinician-scientist at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto.

Yet the news isn’t all bleak: while the number of sepsis cases is rising by roughly nine per cent each year, in recent years, death rates have dropped significantly, and Canadian researchers have been hard at work identifying promising new treatments for the condition.

An Over-the-Top Immune Response

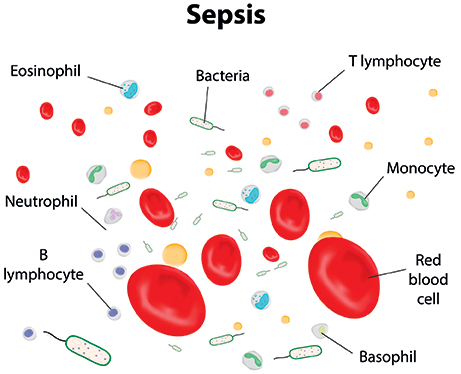

What exactly is sepsis? While it’s sometimes referred to as “blood poisoning,” that term is misleading: ultimately, the instrument of execution isn’t poison or even massive infection, but the patient’s own immune system.

“Sepsis is your body’s toxic response to infection,” explains Marijke Vroomen Durning, a Montreal health writer and media spokesperson for Sepsis Alliance, an organization aimed at raising public awareness of the syndrome and supporting survivors. While it’s not clear why, in some cases, an infection sets the immune system spiralling out of control. And the infection needn’t be caused by something as serious as surgery: any procedure or wound that can introduce bacteria into the body—including the insertion of a catheter to empty the bladder—has the potential to result in sepsis.

When a virus, bacterium, or fungus (such as certain strains of yeast) gets into your body and churns out copies of itself, it can release various toxins, which in turn trigger the release of intensely inflammatory chemicals. So far, so good—after all, it’s these compounds that rally the white blood cells that help rid your body of infection. However, “in high enough concentrations, these inflammatory chemicals cause your cells and organs to fail,” explains Dr. Anand Kumar, a prominent sepsis researcher and professor of medicine at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg.

Photo: Dreamstime/Josha42.

This over-the-top immune response is called sepsis. Sepsis that progresses to the point of organ failure is classified as “severe.” When sepsis triggers the most dramatic type of organ failure—cardiovascular collapse—the result is referred to as “septic shock.” Not surprisingly, the more grave the illness, the higher the risk that the condition will be fatal: according to figures from the Canadian Institute for Health Information, in 2008–09, 20.9 per cent of Canadians with sepsis died of the condition, versus 45.5 per cent of those with severe sepsis.

Another process, which takes place simultaneously, also contributes to organ damage and failure. Because the immune and blood-clotting systems are intimately intertwined, sepsis switches on the former and the latter, causing tiny clots to form in the blood vessels. If clots pile up and block the blood vessels that feed a particular organ, the organ is starved of oxygen and nutrients, resulting in damage and loss of function.

When logjams of clots block circulation to the fingers, toes, arms, and legs, the affected tissues can die and turn gangrenous, spurring the spread of infection to adjacent areas. “If you don’t get any blood flow to the limbs, doctors have to cut them off to save you,” notes Paul Kubes, lead researcher for the Alberta Sepsis Network and director of the University of Calgray’s Snyder Institute for Chronic Diseases.

Organ failure can itself sometimes open the gates to further systemic infection, says Barry Janssen, a scientist and sepsis researcher at the Lawson Health Research Institute in London, ON. “If the gut fails, bacteria from the gut can get into your bloodstream,” he explains.

Treating Sepsis

There are relatively few things doctors can do to treat sepsis, and they’re the same strategies that have been in use for decades.

“So far, few things have stood the test of time,” Dr. dos Santos says. “One is identifying the organism responsible and trying to control the source,” by, for instance, taking an antibiotic to fight a specific strain of bacteria.

Still, until recently, antimicrobial drugs were given relatively short shrift, Kumar says. Giving these drugs “wasn’t a huge priority,” he says, “because the thinking was that once the inflammatory cascade had been triggered, it continued on its own,” even if the infection itself was brought under control.

The other mainstay of treatment is using the means available to temporarily take over the functions of failing organs to give the body time to recover. This includes strategies such as using a mechanical ventilator to take over for failing lungs and using a dialysis machine to step in for faltering kidneys.

“There is evidence that supportive care might be useful,” Kumar says. Yet even life-support has limits: not only do treatments such as dialysis not work as well as the organs they’re intended to pinch-hit for, there are no interventions to protect or support the brain, Kubes says. Currently, all doctors can do is use sedation to ease brain-related symptoms of sepsis.

So perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that, until a relatively short time ago, up to 50 per cent of people who developed sepsis ultimately died of it.

Thus far, attempts to broaden treatment options have been disappointing, to say the least. According to dos Santos, who is also an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, 104 randomized clinical trials in the field of sepsis have failed to produce positive results. In fact, the only drug ever to have been approved for treating severe sepsis—a sort of combination anti-inflammatory/anticoagulant called recombinant human activated protein C, or rhAPC—was withdrawn from the market by the manufacturer when studies conducted after its release showed it had little effect on outcomes, regardless of its whopping price tag. (Many Canadian scientists, dos Santos included, are hard at work pursuing promising avenues for future therapies.)

“We have very good ways to fight infection; what we don’t have are ways of fighting the body’s response to the infection,” says Dr. Gordon Rubenfeld, chief of the Trauma, Emergency, & Critical Care Program at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and a professor of medicine at the University of Toronto. And thanks to growing antibiotic resistance and declining investment in developing new alternatives, we may not even be able to fight infection for much longer.

On the bright side, scientists have discovered how to use the interventions we do have to much better effect. Pioneering studies led by Kumar and confirmed by other researchers have shown that, “for every hour delay in starting antimicrobials after cardiovascular collapse, you increase the risk for imminent death by about 7½ per cent,” Kumar says. Seven or eight years ago, prior to Kumar’s landmark work, “the median time to get antibiotics on board was about six hours,” he says. “In Winnipeg, we’ve cut our times down to about 2½ hours, so our mortality for septic shock is down from 65 per cent to about 20. Since we get about 500 cases of septic shock annually, we’ve saved about 200 lives a year. Giving antibiotics within an hour of recognition was adopted as an international recommendation, and we’re seeing huge decreases in mortality across the board.”

“We’ve learned the really basic stuff—early recognition, early antibiotics, and fluids are the most important,” adds the University of Toronto’s Dr. Rubenfeld. “This stuff isn’t very sexy,” he acknowledges, but says that simply applying this practice systematically has revolutionized the treatment of sepsis.

Alarm Bells

Because the symptoms of sepsis in its earliest stages are impossible to differentiate from those of a garden-variety viral infection such as the flu, early recognition turns out to be a bit trickier than it sounds. So when should you suspect you might have sepsis?

First, it’s worth knowing what kinds of factors, besides age, are linked with an increased risk. These include diabetes; chronic liver, lung, and kidney disease; lack of a spleen; and an immune system impaired by disease and/or medications such as steroids and chemotherapy drugs. If you have any of these conditions, it’s crucial to be on the alert if you have any kind of wound, surgery, or other procedure (including getting a tattoo or spa pedicure) that can introduce infection. While it’s always best to take precautions against getting infections—such as by getting an annual flu shot, washing your hands frequently, and observing stringent hygiene measures when caring for wounds or using devices such as catheters—doing so is even more important if you have one of these conditions. A recent history of any of these things or any kind of infection, ranging from the flu to a bladder infection, should set off alarm bells should you develop any of the possible symptoms of sepsis. So what are some of those potential clues?

“A change in mental status is one of the warning signs,” says Mark Lukewich, a senior lab demonstrator at Brock University in St. Catharines, ON, who received a CIHR scholarship for his Ph.D. research on sepsis.

Thornhill’s Rhea Copeland, for instance, appeared to be delirious after coming out of surgery. “My daughters said I was acting very strangely—I was talking out of my head,” she says. While medical staff thought Copeland was simply taking a bit more time than usual to shake off the effects of the anaesthetic, her daughters Gail and Tammy knew something wasn’t right. “She had had three surgeries in the previous three years, so we knew what she was like when she was recovering, and this wasn’t following the same pattern,” Gail recalls. It took Gail and her sister three days to convince medical personnel of this before a surgeon was called in to clean out the infection in her abdomen.

For Chatham, ON, resident Shirley Hill, the first clue was the agitation and anxiety she began to feel while her brother was visiting on the morning following her procedure. “My mind was racing a mile a minute and I just kept thinking, Why don’t you leave so I can go to bed?” she recalls. “When he left, I just burst into tears.”

Fever (particularly if it’s very high or accompanied by strong chills or a severe headache) is another hint that something may be amiss.

After Hill went to lie down, her son, who’d read the literature Hill had been given upon discharge from the hospital, checked Hill’s temperature and discovered it was slightly elevated. “He kept coming back every 15 minutes to take my temperature, and it just kept going up,” she says, “so he said, ‘You have to go to the hospital.’” Feeling fluish but not direly ill, Hill resisted, but her son insisted, so she gave in just to get him off her back. “He saved my life,” she says. “If he hadn’t been there, I would have gone to sleep and probably would have died in my bed. Having people know what to look for is really, really important,” she says. This is especially true if your own mental functioning may be impaired.

By the time Hill arrived at her local hospital’s ER, which is only a 10-minute drive from her home, she was having such difficulty breathing that she felt as if she’d forgotten how. (Rapid breathing is another possible red flag, as are pale, cold or clammy skin, rapid heart rate, blue lips, low or no urine output, severe abdominal pain, and severe localized pain.) “They triaged me really quickly and took my blood pressure, which I’m sure was nose-diving,” Hill recalls. “When I said I’d had a kidney stone taken care of the day before, they started adding up the facts.”

Almost immediately, Hill was sent up to ICU with a diagnosis of probable sepsis. In the 30 minutes it took to confirm that suspicion, Hill had developed full-blown pneumonia and a raging gastrointestinal infection. “All sorts of things started surfacing,” she says, including a rash of dark spots (caused by tiny clots) that began blooming on her skin. (This type of rash—which typically doesn’t whiten when pressed—is another potential warning sign.) “Within an hour, I went from feeling relatively normal to being at death’s door.” Indeed, once the worst of Hill’s ordeal was over, physicians told her that by the time she had arrived in hospital, her condition was so grave that she would have died within two hours without treatment.

While both Copeland and Hill survived their encounters with sepsis, neither was left unscathed.

Copeland, who spent seven weeks in the ICU followed by five weeks at a rehabilitation facility, is grateful to have regained her ability to do most normal tasks after waking up in the ICU unable to move anything but her eyes. However, now she needs a walker to get around. Her hands feel swollen and don’t work perfectly, and, she says, “I hurt from my toes to my head.” Still, she says, “I eat well, I sleep well,” and she obviously cherishes her family’s company.

Shirley Hill spent nearly four months able to walk only the distance from her bed to the bathroom. She still tires easily—she needs to rest after having a shower. She has difficulty sleeping and feels faint if she has to stand for any length of time; she waits in the car while her husband stands in the grocery store checkout line. Once very socially active, she now feels completely drained after spending a few hours with company and finds the noise at a typical busy restaurant makes her feel frantic.

“I’m glad I’m here,” she says. “We don’t hear anything about sepsis, and yet every two minutes, someone in the United States dies of it. Making the public more aware of it could save lives. I mean, if my son hadn’t been on his toes, we wouldn’t be having this conversation.”