When someone close to you is facing a life crisis, offering to help is kind—but you can do more

By Wendy Haaf

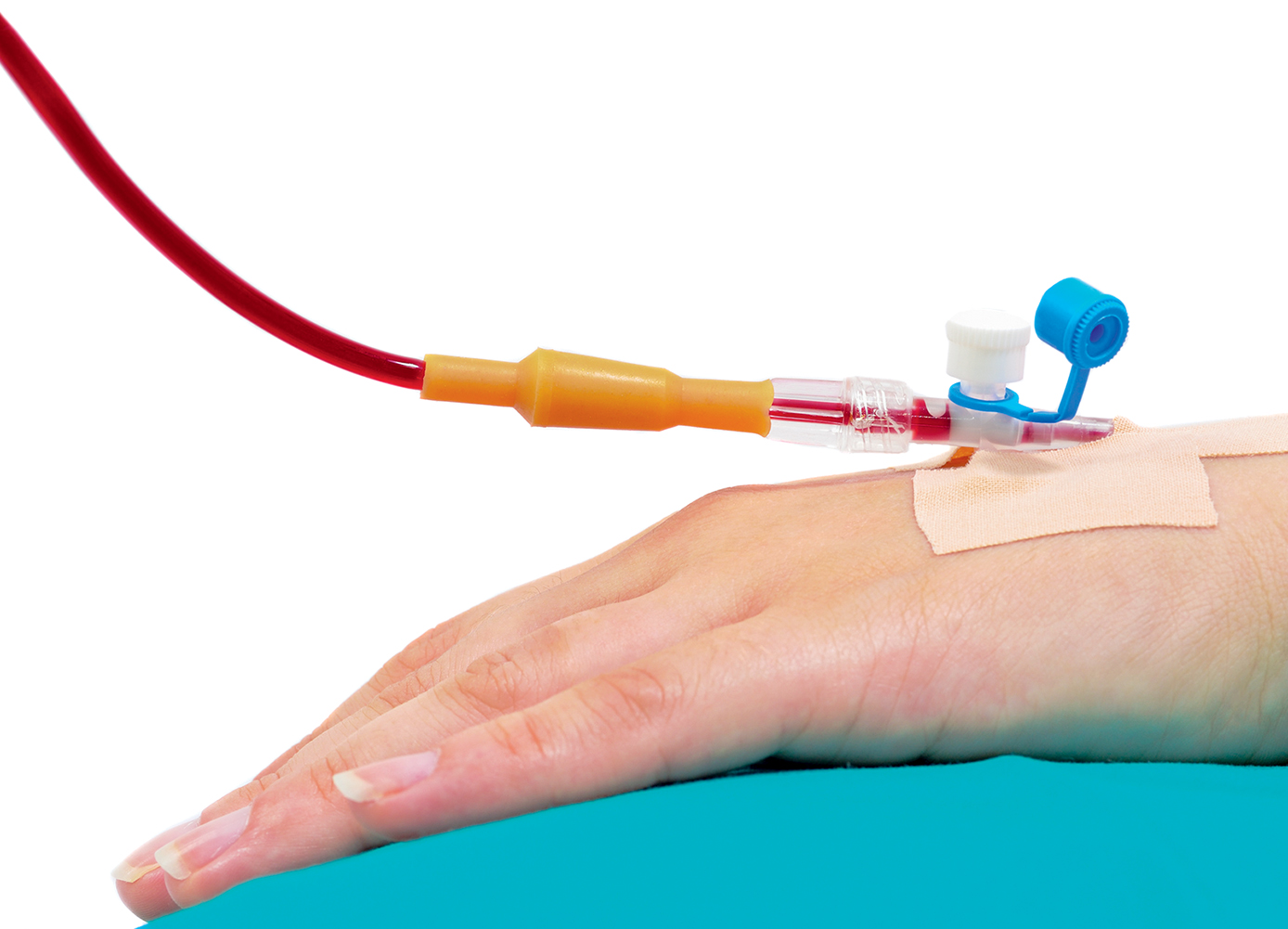

Photo: iStock/MichaelDeLeon.

Good friends are one of life’s greatest treasures, and they only grow more valuable, since strong, supportive relationships seem to foster mental and physical health as we age. But whether it’s divorce, serious illness, the death of a spouse, or having to provide ongoing care for a family member, when a loved one is going through a difficult time, often we’re not sure how best to help. So we asked a few people who have navigated those waters to share the deeds that helped keep their noses above the surface, as well as the ropes they wish someone had thought to throw their way.

Offer Specific Help

On hearing a friend’s bad news, it’s natural to blurt out, “Let me know if there’s anything I can do.” But while well-meaning, that offer is almost universally unhelpful, and here’s why: it puts the onus on the recipient, and many of us have difficulty asking for help at the best of times. In the wake of a jolting life event, “you’re in shock and you don’t think clearly,” says Carol King of Kitchener, ON, who is living with a recurring cancer. “People aren’t going to know what they need,” says Karen Humphrey of Chilliwack, BC, who was widowed suddenly in 2018.

There are at least two better alternatives to such a vague, open-ended offer: you can either pitch in where you see or anticipate a need, or you can think of three specific tasks you’d be willing to do and ask the person in question which of his or her needs is most pressing.

“Just be proactive,” urges caregiver and advocate Carole Ann Alloway, who co-founded the Toronto-based Family Caregivers Voice. “There are simple things for you to do that would make life easier.”

In the case of a death, that might include accompanying the friend to the funeral home and helping to plan the funeral, Humphrey says. “I did it all myself, and it was horrible.”

Suzanne Boles of London, ON, says that at the unveiling ceremony for her husband’s headstone, one friend posted herself at the cemetery gates with a sign, stopping visitors to provide directions. “I was really touched by her kindness,” Boles says.

Other possibilities include driving someone to medical appointments, providing a caregiver with a few hours of respite, lawn-mowing, dog-walking, and grocery shopping. And if it’s something you can do on an ongoing basis, “that would be fantastic,” Alloway says.

Following a divorce or a partner’s death, taking over or helping with tasks previously handled by the partner “can be a lifesaver,” Humphrey says; this is especially true when it’s a job your friend has never done before. “For instance, my neighbour helped me with my smoke alarms when they all needed replacing.”

If you’ve dealt with a particular situation before or have some kind of special expertise, consider whether your experience might prove helpful, whether it’s filling out forms, translating medical terminology, photographing items for an estate sale, or letting out a dress. When motivational speaker Frances Hickmott of London, ON, needed to create separate quarters for her late sister’s children while they grieved their mother’s death, a friend whipped up a room divider. “She made it look effortless,” Hickmott recalls. And during Hickmott’s divorce, another friend, a lawyer, helped review the legal papers.

“Just think about what would really make your day or week,” King suggests, and do that. All it takes is a little imagination. When she could barely leave the house due to a prolonged bout of back pain but needed a new outfit, Hickmott was filled with gratitude when a friend bought a selection of pieces, brought them over, and then returned the items that didn’t fit.

One last thing to keep in mind: offers of help often slow to a trickle in the weeks and months after an event, but the need doesn’t end.

Bring Food

“When you’re in mourning, you have no energy to think about cooking and shopping,” Hickmott says, and the same is true when you’re seriously ill. Moreover, if you’re a caregiver, “making and cleaning up three meals a day plus snacks is very time-consuming,” Alloway says.

But before you make any plans, it’s best to check with someone close to the person in need to learn about his or her preferences, any items that might be off the menu for other reasons (interaction with medications, for example), and, in the case of illness or treatments that cause appetite loss or nausea, foods the person might find particularly appealing.

Dishes that can be popped into the oven to warm—even store-bought lasagna—or frozen until needed are good options, as are snacks and breakfast fare, such as muffins and bagels. King’s son and daughter-in-law even drop by to cook dinner in her home occasionally—after checking to see whether she’s up to it. For people in hospital or their family members, gift cards for the coffee shop on the premises or even parking passes will also be appreciated.

Not arriving empty-handed when you stop by for a visit relieves the pressure on your friend to act as host or hostess. “Stop by the grocery store and pick up some fresh fruit, or some grapes and a piece of cheese,” King suggests. That way, the only preparation and cleanup required is a quick rinse of the fruit, plate, and knife. And when people drop in, she adds, “I like it when they stop at Tim’s, so I don’t have to make coffee.”

Observe Extra Visiting Etiquette

Before dropping by, be sure to call ahead, as King’s son and daughter-in-law do, to get the all-clear first: someone with cancer may have to avoid visitors during certain phases of the treatment cycle to protect against infection. And since grief, illness, and caregiving are exhausting, be alert for clues that someone’s energy is flagging, or plan to stay only a short time.

Avoid Platitudes

It’s hard to know what to say when you’re confronted with the news that a friend has been diagnosed with a serious illness or lost a loved one. Unfortunately, some of the automatic, stock responses that might come to mind can actually worsen the person’s pain.

For example, King says, when someone who hasn’t seen her for a long time bumps into her and she explains why she’s lost her hair, “they give you a look of absolute pity, as if they’re wondering what they’re going to wear to the funeral,” and then paste on a fake smile and insist, “But you look great.” Instead of the well-meaning lie, it might be better to ask what else is going on in the person’s life. Another no-no: Someone who has been diagnosed with cancer will probably find it downright offensive if you say, “Everything happens for a reason.”

In the wake of a loss, “don’t say, ‘This will pass,’” Humphrey urges. “It isn’t going to pass. The person they love is gone, and now they have to figure out how to live without them.”

Make Small Gestures

Jotting down a short note and popping it in the mail or delivering a small treat, such as a favourite candy bar, can add a note of brightness to a recipient’s day, yet these acts require minimal effort on your part. The same goes for texting just to share that the person is in your thoughts and—if appropriate—prayers, or sharing a resource he or she might find useful.

“Being sick is boring,” King says, and diversions are welcome. “I love it when somebody says, ‘I just read this fabulous new mystery’—I love mysteries—and drops it by.” Another of King’s friends, who is also living with a chronic illness, regularly shares the names of Netflix series King might enjoy.

An invitation to an outing or event can help someone who’s learning to live solo after a split or a partner’s death feel less alone. This goes double during holidays, which are particularly difficult under such circumstances. That said, don’t take it personally if the overture isn’t accepted. Humphrey, for example, found that “movies were too loud, and [fictional] deaths [in films] were triggering.”

You can provide a caregiver with some much-needed me time by offering to sit with his or her charge for a few hours. Another way to demonstrate you care: call the caregiver specifically to ask how he or she is doing, rather than asking after the patient. If the care recipient is able, call directly for updates, instead.

Show Up

Simply showing up is one of the greatest gifts you can give a friend who’s dealing with one of life’s profound heartbreaks. Admittedly, this can be personally wrenching when you care deeply for that person.

One of King’s dear friends, for example, simply couldn’t handle the fact King might die and so kept coming up with reasons to cancel visits, eventually going AWOL entirely. “If she had said, ‘Look, I’m having a really tough time dealing with how ill you are; could we just talk on the phone instead?’, that wouldn’t have hurt me as much,” King says.

If you’re having difficulty mustering your courage, checking in by phone and offering a non-judgmental ear is one way of offering support.

“Ask open-ended questions so the person can either talk about what’s difficult or just chit-chat,” Alloway suggests.

“Part of being sick is having to play the role of brave little soldier, which can be exhausting,” King says. “We have times when we need someone who will just let us vent. Sometimes I feel like sitting in a corner and howling, and I just need someone to say they hear me.”

And if someone is bereaved, “don’t be afraid to bring up things that might make us cry,” Humphrey advises. For example, sharing happy memories about the person who died can be comforting despite the tears it elicits, and in fact, avoiding any mention of him or her can cause far more pain. “Don’t feel that you have to make it better—you can’t.”

Providing companionship while pitching in with tasks such as sorting through a departed loved one’s belongings or even silently sharing a cup of tea may seem minor, but that’s just not the case.

“Sitting with someone in her grief is the most powerful thing you can do,” Humphrey stresses. “Yes, it is uncomfortable—but that is love.”