You may be among the 50 per cent of those using a heartburn medication who shouldn’t be

By Wendy Haaf

Photo: iStock/ChrisChrisW.

Do you take a daily medication to treat heartburn with a generic name ending in “prazole,” such as esomeprazole, omeprazole, or lansoprazole? Or do you down an over-the-counter counterpart, such as Olex, twice a week or more? In either case, it may be time to reassess whether you really need it.

While these powerful medications, known as proton-pump inhibitors, or PPIs, definitely have their place, some evidence suggests that they’re being used inappropriately by 50 per cent of those who take them long-term. That’s important, since, like any other effective medication, prescription or otherwise, PPIs pose uncommon but potentially serious risks—risks that obviously aren’t worth taking if you don’t need to.

Nevertheless, a large and growing number of people of retirement age take them more than occasionally. According to a Canadian Institute for Health Information report, nearly one in four people 65 or over (23.5 per cent) used PPIs regularly between 2012 and 2016, with chronic use climbing over that period in all provinces but Ontario. In fact, this class of medications is one of the most commonly used in Canada, second only to cholesterol-lowering statins.

So when is it worthwhile to continue taking a PPI long-term? And if you and your caregiver decide that you may not need to do so, what next? We asked the experts to answer these and other common questions about heartburn meds.

What are the potential risks of ongoing PPI use?

After these medications had been on the market for some time, evidence began to emerge suggesting that, when used for longer than four to 12 weeks, they might increase the risk for certain health conditions.

“They can cause low B12 and low magnesium levels,” says Camille Gagnon, the assistant director of the Canadian Deprescribing Network at the Montreal University Institute of Geriatrics research centre. “PPIs have also been linked to more harmful events,” she adds, including fractures, pneumonia, kidney problems, and an intestinal infection caused by the bacterium C. difficile. (If severe, C. difficile infection, which typically occurs in hospital, can sometimes become life-threatening.)

When it comes to the magnitude of these risks, there is some disagreement. For example, while Kent MacLeod, an Ottawa pharmacist, cites a study in which there was an additional one death per 100 people among users versus non-users of PPIs, some experts view such statistics skeptically.

“I think there’s good agreement among gastroenterologists, particularly those who work in this area, that the potential risks of PPIs have been seriously overcalled,” says Dr. David Armstrong, a gastroenterologist and associate professor at McMaster University in Hamilton, ON. That’s because most of the information we have is based on non-randomized trials that simply track people who use the medications. Consequently, the increase in risks could be due at least in part to some other factor PPI users have in common—for example, the fact that they’re more likely to have multiple health problems than are people in the general population.

What’s considered appropriate—and inappropriate— use of PPIs?

There are situations in which taking PPIs long-term is recommended, for example, to reduce an elevated risk for serious health problems such as bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract and esophageal cancer in those who take a daily non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (an NSAID such as ibuprofen or a corticosteroid), who have had a major episode of stomach bleeding, or who have damage to the esophagus caused by stomach acid escaping upward (Barrett’s esophagus or severe erosive esophagitis).

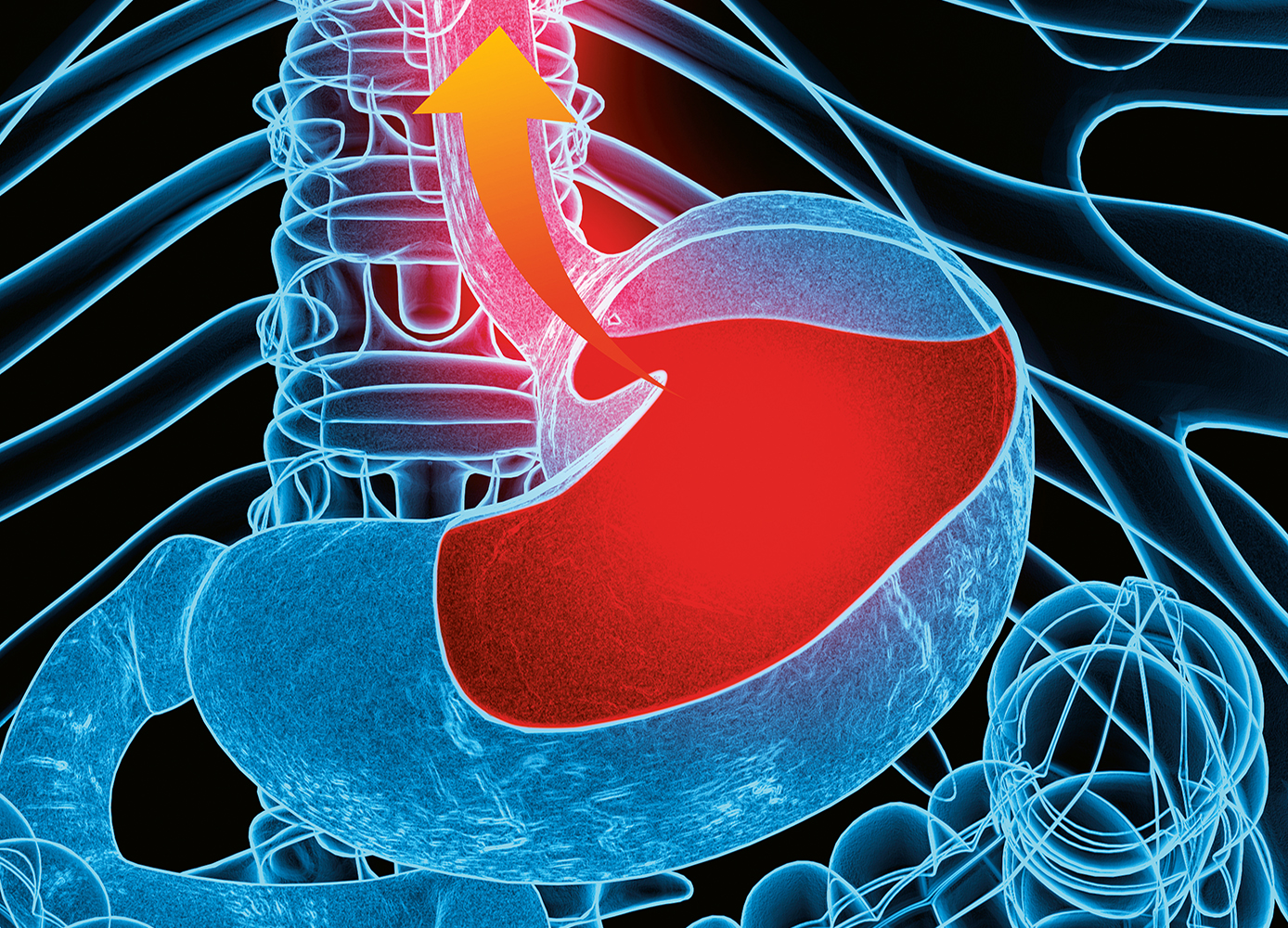

PPIs are also used to suppress stomach acid in people who have mild to moderate inflammation of the esophagus caused by gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD—with GERD, the most common symptom of which is heartburn, stomach acid frequently flows backwards, up towards the back of the throat).

Used in these circumstances, “studies show that within four to eight weeks, there’s 90 per cent healing,” says Barbara Farrell, a pharmacist and scientist at the Bruyère Research Institute and the CT Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre in Ottawa and the lead author of evidence-based guidelines on deprescribing PPIs. While it’s often possible to then stop PPIs, people commonly continue taking them indefinitely.

Another large contingent of people taking PPIs chronically don’t seem to have a good reason for doing so in the first place. “In studies on people taking the drugs, roughly half the time there’s no documented reason for ongoing use,” Farrell says.

Consequently, it’s now recommended that people taking PPIs periodically reassess their options. “We’re not saying that everybody who’s on these drugs should stop them,” Farrell stresses. “What we’re trying to do, through the tools we’ve produced, is to help patients, prescribers, and pharmacists make informed decisions about when it’s appropriate to continue.”

How do I decide whether to continue taking a PPI?

Talk with your doctor or pharmacist to review why you’re taking the medication. If you’ve been taking it to quell heartburn, it’s worth asking whether one of the other drugs you’re taking could be contributing to the problem. “There are medications that can make heartburn worse,” Farrell says. Sometimes, changing the dose or switching to a different drug class can help.

If I decide to stop, what next?

When it comes to stopping PPIs, the literature isn’t clear whether there’s a best way of doing so. “You may either take it one out of every two days or cut the dose by half, but you have to remember that a lot of these pills you can’t cut in half,” the Deprescribing Network’s Camille Gagnon says. Talk with your doctor.

If you experience rebound symptoms, that doesn’t necessarily mean you need to resume taking the PPI regularly: often, occasional episodes of heartburn can be managed by using a product such as Tums or Gaviscon.

“Some people may need to go back on a PPI at a low dose or use it on demand,” Farrell says. “Other people might use a different category of drug, such as cimetidine or ranitidine, but in elderly people, we typically don’t recommend that because those drugs can cause confusion.” (The latter medications belong to a drug class known as H2 blockers.)

Are there other things I can do to help manage heartburn and reflux?

Lifestyle changes can go a long way towards managing heartburn symptoms. For example, quitting smoking, cutting back on caffeine, and losing just a kilo or two if you’re overweight can help the valve at the top of the stomach function more effectively, so acid is less apt to escape. And, ladies, if you’ve gained a bit of weight since you last bought a bra, you may want to consider shopping for some new, better-fitting ones. Farrell says that several of her clients have found considerable relief after doing this, since a too-tight band can bind across the valve where food empties into the stomach.

Even simple changes in the way you eat can often improve symptoms, not to mention your overall health.

Andrea Hardy, a registered dietitian in Calgary, often recommends spacing food intake more evenly throughout the day rather than having a big, higher-fat dinner. “I find that makes a really big difference,” she says. “Eating mindfully—slowing down and actually chewing and experiencing your food—can also play a big role,” she adds, since you’ll be more likely to stop when you’re satisfied rather than stuffed.

“Getting enough fibre is another key piece,” Hardy says.

In addition to helping the stomach contents move more easily through your system and preventing constipation (which itself can contribute to reflux by increasing pressure on the gut), fibre (specifically the soluble type found in foods such as beans) nourishes beneficial species of bacteria in our bodies that carry out important tasks such as helping to grow the protective mucus lining of the stomach, says Ottawa pharmacist Kent MacLeod. “You can’t replace those bacteria; you have to feed them,” he explains, noting that a healthy balance of gut bacteria appears to play a pivotal role in many aspects of our overall health.

“The average Canadian or American gets about half of the fibre he or she needs per day,” Hardy explains. “Making sure we get more from plant-based foods is important.” Some of Hardy’s favourite strategies for doing so include aiming for two cups of vegetables at lunch and dinner, sprinkling nuts and seeds on yogourt, adding ground flax seed to smoothies, and incorporating beans and lentils into more meals. A registered dietitian can help you determine whether you’re getting enough fibre, and if you’re not, he or she can guide you in adding it gradually to your diet, since a too-abrupt change can cause symptoms such as bloating.

MacLeod says that for the majority of people whom he’s helped transition away from PPIs, a simple dietary shift and some fibre has been enough to bring symptoms under control in the long term. “It’s fascinating that the remedy is doing things that are also proven to reduce cancer, heart disease, and cholesterol,” he says.

What if my symptoms are still troublesome, or if I’m just not ready to try stopping PPIs because there’s simply too much going on in my life to make any changes?

“It’s perfectly reasonable to restart the medication,” Armstrong says, particularly if your symptoms are affecting your quality of life (and possibly even your health), for example, by interfering with sleep. You can always try to stop again in future, at which time perhaps circumstances may be more favourable.

With a bit of luck and support, you might find yourself in the company of people like Hardy. “As someone who struggles with chronic reflux, I use medication judiciously,” she says. “I just spent three days in Vegas, so I took my H2 blocker in case of flare-ups. Finding that balance to reduce the overall recurrence and taking medication when the benefits outweigh the risks absolutely makes sense.”

Resources