Dodge the crowds and you’ll find the city as beautiful as ever

By Michael Ryval

Ponte di Rialto and the Grand Canal. Photo: Alain Verronneau.

On a brilliant sunny day in September, we boarded Vaporetto No. 1 at Venice’s main train station, Santa Lucia, and proceeded down the Grand Canal. To the left and right of us, one magnificent palazzo after another passed as if in review.

Palazzo Ca’ d’Oro and Ca’ Rezzonico.

Photos: Alain Verronneau and Dreamstime/Lejoch.

Farther along was Ponte di Rialto, a spectacular covered 17th-century stone bridge, from which a handful of people waved to us. Sitting at the front of the vaporetto and basking in Venice’s warm air, we waved back. The bright, friendly atmosphere was more or less as I remembered it, having been to Venice more than 40 years earlier.

Then we passed Ca’ Rezzonico, another white marble palazzo designed by Longhena, which was much later turned into the museum of 18th-century Venice. As we approached the entrance of the Grand Canal, we could see Santa Maria della Salute, a looming basilica that calls to mind London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral. Yet another of Longhena’s designs, Santa Maria was built in the mid-17th century to mark the end of a plague that wiped out almost one-third of Venice.

Arriving at the busy Piazza San Marco. Photo: iStock/Grafissimo.

Finally, we stopped briefly at Piazza San Marco—St. Mark’s Square—that elegant public square at the heart of Venice.

Venice is one of the world’s most popular destinations, said to be visited by 20 million people each year, many of whom arrive on endless waves of cruise ships. Very soon, my wife, Janet, and I realized that we’d better find ways to enjoy this historically rich and beautiful city without being overrun.

A Tide of Humanity

In a sense, Venice is two cities, one made up of huge crowds who make it hard to appreciate the elegant Ponte di Rialto and Piazza San Marco. The other is the exact opposite, with quiet piazzas that front on baroque churches, tall tenement buildings, and nearly deserted canals that bisect the islands of Venice. So long as you wander off the crowded path, you can avoid the crowds and truly enjoy this fabulous city.

We certainly had a taste of the raucous hubbub later that day, after checking into our hotel in the Sant’Elena area and re-boarding the vaporetto that took us back up the Grand Canal. We alighted at the San Toma station and in a few minutes stood before Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari (a.k.a. the Frari), a magnificent 14th-century brick Gothic-style minor basilica built for the Franciscan order. Deliberately austere, it’s home to several wonderfully vivid paintings, including Bellini’s “Madonna and Four Saints” and, over the main altar, Titian’s “Assumption of the Virgin.” It also has a wonderful cloister, which was nearly deserted.

Intending to venture across the Grand Canal, we headed to the Ponte di Rialto with the objective of eventually reaching Piazza San Marco. Getting to the bridge wasn’t difficult—crossing it was entirely another matter. From out of nowhere, a tide of humanity blocked our passage and we had to step to the edge of the bridge to get out of the way. Finally, when a gap appeared, we dashed across the canal.

It was no different walking along the narrow passageways to Piazza San Marco. “Where did all these people come from?” I muttered as we pushed past the dense crowds.

Basilica of San Marco entrance. Photo: iStock/Tomch.

Minutes later, we stood in Piazza San Marco, which was hard to see given the flood of people. To our left stood the 950-year-old Basilica of San Marco and to the right were the covered galleries of the Procuratie, which now house famous cafés such as the Florian. We didn’t linger long, though, pushing our way to the vaporetto landing. Within minutes, we were back in Sant’Elena, where it was blissfully quiet.

That outing provided our first quick lesson about Venice, a lesson that was reinforced that evening when we had dinner at Ostaria da Rioba, in the Cannaregio area. Sitting next to a canal, where the occasional boat quietly slipped by, we enjoyed our meal of scampi, dorade, a bottle of Valpolicella, and a cheese plate. As we watched couples wandering by or stopping to check the menu, we savoured this tranquil scene as proof that Venice was, with the crowds much in the background, quite beautiful.

The Quintessential Venice

Campo di Ghetto Nuovo. Photo: Alain Verronneau.

There were few people the next day when we returned to the Cannaregio district and visited the Ghetto (taken from the word geto, which means “mortar foundry”). In 1516, it became notorious as the first quarter in Western Europe where Jews were confined in crowded tenements. After a brief walk around Campo di Ghetto Nuovo, which features a stark Holocaust Memorial, we visited the Museo Ebraico di Venezia, which documents the 800-year-old history of Venetian Jews, including their persecution during the Second World War. Among the displays are many ritual objects created by silversmiths and textile artisans that include Torah covers and rimonim—pomegranate-shaped bells decorating the Torah scrolls. Entrance to the museum also provided us with a guided tour of three synagogues—or Scuola, as they are called.

“They call this the summer synagogue—because it’s well ventilated,” our guide, Francesco, told us, referring to the large windows in the Levantine synagogue built by Jews who hailed from Istanbul. “Across the way is the winter synagogue, which has proper heating,” he said, pointing to the Scuola Tedesca, which was founded by German Jews in the 18th century.

From the Ghetto, we moved across the Grand Canal to Ca’ Pesaro, which is now the International Gallery of Modern Art. The museum features a series of 10 rooms with work by a wide variety of 20th-century artists, including de Chirico, Miró, Klimt, Chagall, and Kandinsky. By the time we emerged, it was almost 5 o’clock, so we had time simply to wander through the narrow streets.

Turning a corner, we encountered the quintessential Venetian scene: a gondola with two passengers travelling under one of the low pedestrian bridges that join one neighbourhood to another. There were a few people going about their business and, behind them, the lovely pastel-hued houses that line many of Venice’s canals.

With the hope that it wouldn’t be as crowded at 10 a.m. as it would be later, we visited the Basilica of San Marco the next morning.

The basilica is a fascinating mixture of Byzantine and Western styles. Passing through the central doorway adorned with Romanesque-Byzantine reliefs, we saw on the ceiling a plethora of 11th-century mosaics by artists from what was once known as Constantinople (Istanbul, today). At the back of the basilica, where it was somewhat crowded, we saw Pala d’Oro, a high altar table and a masterpiece of Gothic art from the 10th century that is regarded as one of the basilica’s treasures.

Palazzo Ducale, from the canal. Photo: Alain Verronneau.

Home of the Doges

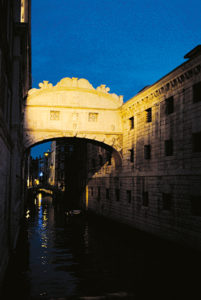

It was far easier to get around Palazzo Ducale next door, the 12th-century home of the doges who for centuries ruled Venice and an expansive empire in the Mediterranean. At the top of Scala d’Oro, or Golden Staircase, we passed into a series of rooms, such as La Sala delle Quattro Porte, where ambassadors waited for their appointments with the Doge. One grand room followed another, and ultimately we moved to the notorious prison in the depths of the palazzo. Along the way, we passed the semidarkened passageway known as Ponte dei Sospiri, or Bridge of Sighs. Its name is said to refer to the sighs of prisoners taking their last look at Venice through the tiny portholes in the passageway.

Emerging from the palazzo, we caught a vaporetto to Giudecca, the island directly across the lagoon from Piazza San Marco. Sitting on the quayside, we had a quiet leisurely lunch at Osteria ae Botti, which provided a view of the passing traffic in the lagoon and beyond it, the Campanile of San Marco. We ventured back to the city and followed the narrow laneways to Santa Maria della Salute, which has a very elegant interior featuring a sacristy dominated by Tintoretto’s “Wedding at Cana.”

A terrasse in Dorsoduro.

Bridge of Sighs.

Our last day in Venice included a visit to Ca’ Rezzonico. The Rezzonico family acquired the status of nobility in the mid-17th-century the way many others did: by buying it outright when the city’s coffers were somewhat depleted. Today this palazzo features a series of staterooms, some of which have magnificent ceilings by Tiepolo, as well as furniture that was found in Venice during the 17th and 18th centuries.

That evening, our last in Venice, we dined at Ostaria Boccadoro, sitting at a table outside in a lovely piazza on the Campo Widmann square. As we enjoyed our mainly fish dinner, including a good bottle of Italian merlot and dessert of tiramisu and crema catalana, we relished the lack of a crowd and the tranquility of a piazza enhanced by the warm Venetian air.

In a distance, Isola di San Giorgio Maggiore from Palazzo Ducale.

Gondeliers waiting.

Photos: Alain Verronneau.