You can reduce your tax bill considerably with pension splitting, but do it wrong and you could end up losing money

By Olev Edur

Photo: iStock/Squaredpixels.

There are very few tax-avoidance strategies left in Canada, as successive governments over the past few decades have closed off all the loopholes that may have once existed. For example, giving a spouse money these days will normally trigger attribution rules, whereby any earnings from that money will be taxed in the giver’s and not the recipient’s hands.

Retirees, however, get a special break—the ability to split pension income with a lower-income spouse or common-law partner to reduce their combined tax bills.

“Pension splitting is a great way to achieve very substantial tax savings if you have two spouses or partners whose incomes are uneven,” says Bradley Goldhar, a senior investment advisor at BMO Nesbitt Burns in Toronto. “I can’t think of any other way that you can make such a big difference to your tax bills.”

The result can in fact amount to thousands of dollars in tax savings, but there are some caveats and wrinkles you need to consider beforehand.

First, different rules can apply to different types of pension income. For example, while you can split up to 50 per cent of the income from a bona fide employer pension plan without restrictions, you can’t split income from a RRIF, a life income fund (LIF), or most types of annuity until you reach age 65. Old Age Security (OAS) payments as well as Canada and Quebec Pension Plan (CPP/QPP) payments can’t be split at all, although the CPP/QPP rules do include provisions for income “sharing” (we’ll explain this next week).

“There can be other restrictions on splitting as well, depending on the terms of the pension plan and the jurisdiction in which you live,” says Geoff MacPherson, a financial advisor with Edward Jones in Newmarket, ON. “Pension rules can vary from one province to another, as can tax and credit rates, so you should consult with a qualified tax advisor in your home province before you initiate any income-splitting strategy.

“You need to consider the big picture,” MacPherson adds. “Everybody’s situation is unique, so you need to create a set of financial planning goals, and then understand how income splitting can fit into those goals, before you go ahead. Nevertheless, even if you were planning not to touch your RRSP savings at all, there can be a big tax benefit to moving some of that money into a lower-income spouse’s hands.”

“The basic reason for income splitting is to take income from someone who’s taxed at a higher rate and move it into the hands of someone who’s taxed at a lower rate,” says Daniel Laverdière, a senior manager of the Expertise Centre at National Bank Private Banking 1859 in Montreal. “If your income is lower than your spouse’s, then generally you shouldn’t split your income with him or her. But there are some exceptions to this rule.”

Consider Marginal Effective Tax Rate (METR)

For one thing, using only marginal tax rates to calculate the benefit (or lack thereof) of pension splitting can be misleading because the clawback of credits and OAS benefits can affect the equation. (Clawback rules effectively mean that the more your income exceeds a certain limit, the more the government “claws back” some of your credits or benefits.) As a result, you need to consider what’s called the marginal effective tax rate (METR).

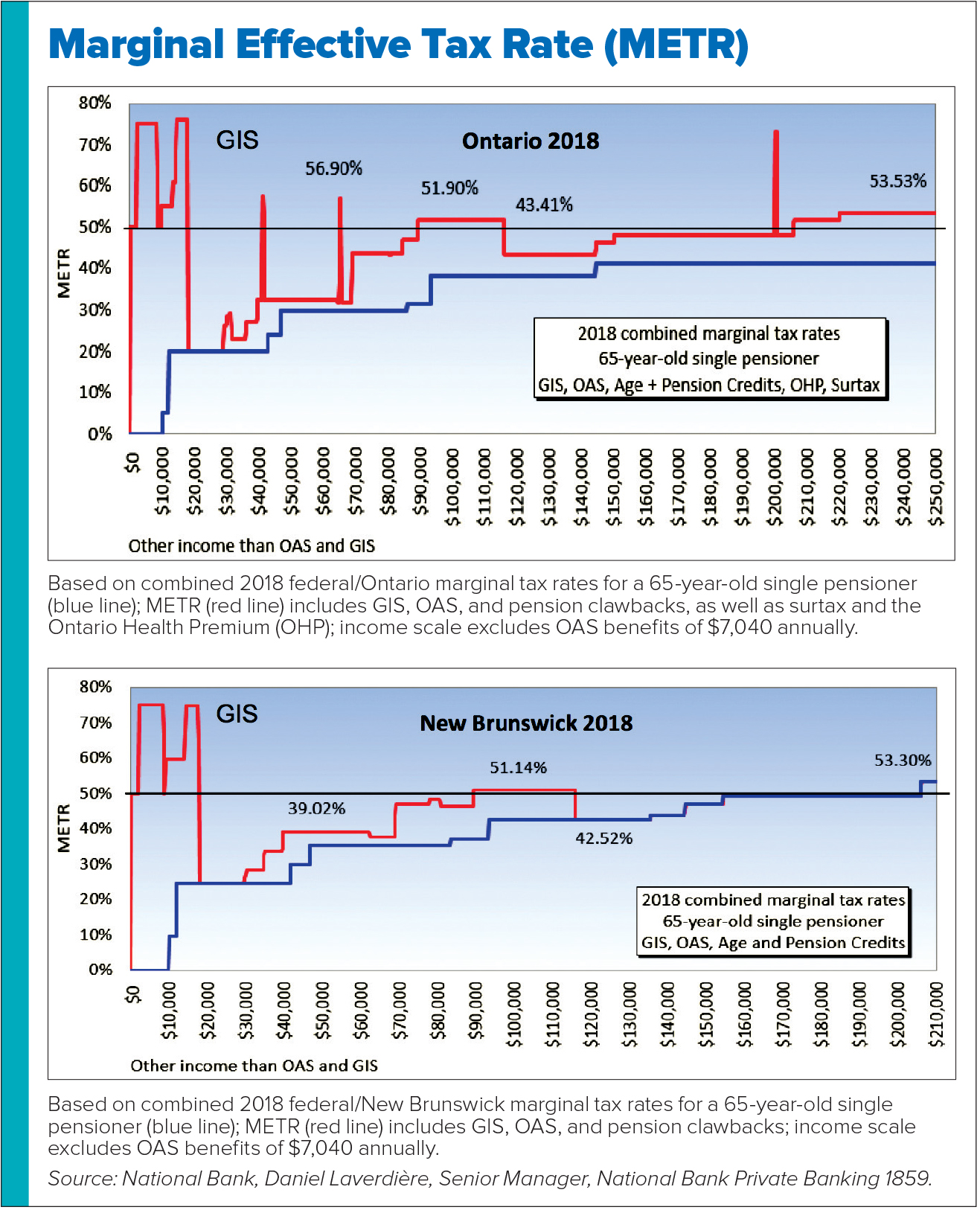

METR takes into account not only tax but also the loss of credits in calculating how much of each dollar of your income the government takes. The two charts below illustrate, for example, the differences between marginal tax rates and marginal effective tax rates in both Ontario and New Brunswick for the 2018 tax year. (Note that these figures apply in these two specific provinces; the tax results for other provinces can vary. And the following is complicated, but bear with us.)

In each chart, the blue line represents marginal tax rates—the rates with which we’re all familiar—as they apply across the income spectrum, while the red line represents METR. The rates are based on a 65-year-old pensioner, taking into account the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS), OAS, and age credit clawbacks in both provinces, plus a surtax and Ontario Health Premium (OHP) increases in that province. (The income figures across the bottom exclude OAS for technical reasons, but that doesn’t affect the general results; the spikes in the Ontario METR result from the way the OHP is applied.)

As you can see in the top left corner of both charts, and as most low-income retirees are aware, the combined clawback on GIS, as well as its “top-up” at low income levels, can result in an METR of as high as 75 per cent; that is, you get to keep only 25 cents of each dollar you receive. (This harsh punishment of lower-income pensioners has been a recurrent topic in Good Times, especially as it relates to retirees trying to withdraw their RRSP/RRIF savings.)

OAS Clawback

If, for example, you pay income tax at a combined federal/provincial rate of 20 per cent but earn enough income to suffer an age credit clawback of 15 per cent, each dollar you earn at that point will effectively have 35 cents deducted—that’s your METR percentage. Similarly, if you earn more than about $77,000, you’ll become subject to the OAS clawback, and when combined with tax, your total cost can quickly soar to a METR beyond 50 per cent.

There is, however, an income range within which it may pay to rethink the basic rules—the roughly $77,000-to-$123,000 range where the OAS clawback applies. As you can see on the charts, METR drops by some eight per cent immediately beyond that range, and doesn’t reach the same level again until income exceeds $200,000 (beyond which it goes a mere percentage point or two higher in these two provinces).

A couple of planning conclusions follow from these figures.

First, someone with an income between $123,000 and $200,000-plus would be ill-advised to split pension income with a partner whose income falls into the OAS clawback range. Depending on actual incomes and the amount being transferred, there could be a METR increase of as much as eight per cent rather than a decrease. “You generally don’t want to transfer pension income to someone who is in the process of losing their OAS,” Laverdière says.

The reverse is true, as well: a retiree in that OAS clawback range could actually reduce METR by as much as eight per cent by transferring some of his or her pension income to a partner with a higher income. “It’s counterintuitive and may not be a big savings in some cases, but it’s still significant,” Laverdière says.

A similar anomaly relates to the clawback of the age credit. This credit is reduced by 15 per cent of net income (from line 236 of your tax return) in excess of $36,976 (for 2018 and indexed for inflation) and is eliminated when income exceeds $85,863 (for 2018 and indexed). So, someone earning $75,000 could reap a 15 per cent windfall by splitting pension income with someone earning $50,000, even though both are in the same marginal tax bracket. And someone earning $40,000 could benefit by splitting with someone earning $20,000, again even though they are in the same tax bracket. “What you’re doing is avoiding the clawbacks by giving money to someone who isn’t subject to them,” Laverdière explains.

Hundreds or Even Thousands in Savings

Furthermore, the charts show that while marginal tax rates are almost universally referenced in calculating the benefits of pension splitting, the actual savings could be far greater than marginal rate differences alone would suggest.

Take someone in Ontario earning $93,000, for example, and thus in a 38 per cent tax bracket (for 2018). If he or she could transfer $3,000 pension dollars to someone earning $43,000 and paying 20 per cent, the tax bracket savings would be 18 per cent, or $540. But the OAS clawback means that METR is actually 51.9 per cent, so the real money-from-your-pocket difference is 31.9 per cent. In other words, rather than saving $540, you would be saving $957 in tax on that $3,000 transfer.

Similarly, someone earning $80,000 and transferring $3,000 of pension income to a spouse earning $60,000 would see a mere two per cent savings based on marginal rates, but the OAS clawback effectively boosts that differential to 17 per cent.

“Sometimes you can both be in the same tax bracket, so splitting your pension would accomplish nothing,” Laverdière says. “But if you factor in the OAS clawback, suddenly there’s a big difference.”

On a transfer of just $3,000, the savings at 17 per cent would be $510, and it should be borne in mind that these are annual savings. On larger splits, the savings could easily reach four digits, so clearly, pension splitting can be a very valuable option for many retirees.

“Pension splitting is 100 per cent an excellent tax planning strategy—provided you do the math,” BMO’s Bradley Goldhar says. “It works best if you can move that income down a notch or two in terms of marginal tax rate, but the OAS clawback can be a key factor, as well. I can’t think of many situations where, given uneven tax levels, pension splitting isn’t advisable.”

Furthermore, there could be a doubled benefit to pension splitting if one spouse has no pension income of his or her own.

“We often advise people reaching age 65 to move some of their RRSP savings into a RRIF right away, even though they’re not required to do it until age 71, just so they can claim the pension income credit of $2,000 each year,” Goldhar says. “If you can split that much pension income with a spouse who has no pension income, then you both may be able to claim this credit. That’s on top of any rate-related tax savings.”

“Many people may not even realize that they don’t need to have a pension in order to benefit from pension splitting,” financial advisor Geoff MacPherson notes. “Fewer and fewer people have defined benefit plans these days, but all you need are some registered savings, and most retirees have some of those. Once you’re 65, you can put some of it into a RRIF, and then the withdrawals qualify as pension income.

“Of course, you need to look at your overall financial plan to see whether and how pension splitting can fit into that plan,” MacPherson says. “But in many cases, there is potentially a lot to be gained.”

NEXT WEEK:

Canada/Quebec Pension Plan (CCP/QPP) Sharing

CPP/QPP pension benefits aren’t eligible for pension-splitting, but you’re allowed to “share” your CPP/QPP pension with your spouse. Find out how that works next week.