This is a city to take long walks in

By Rob and Wendy Lindsay

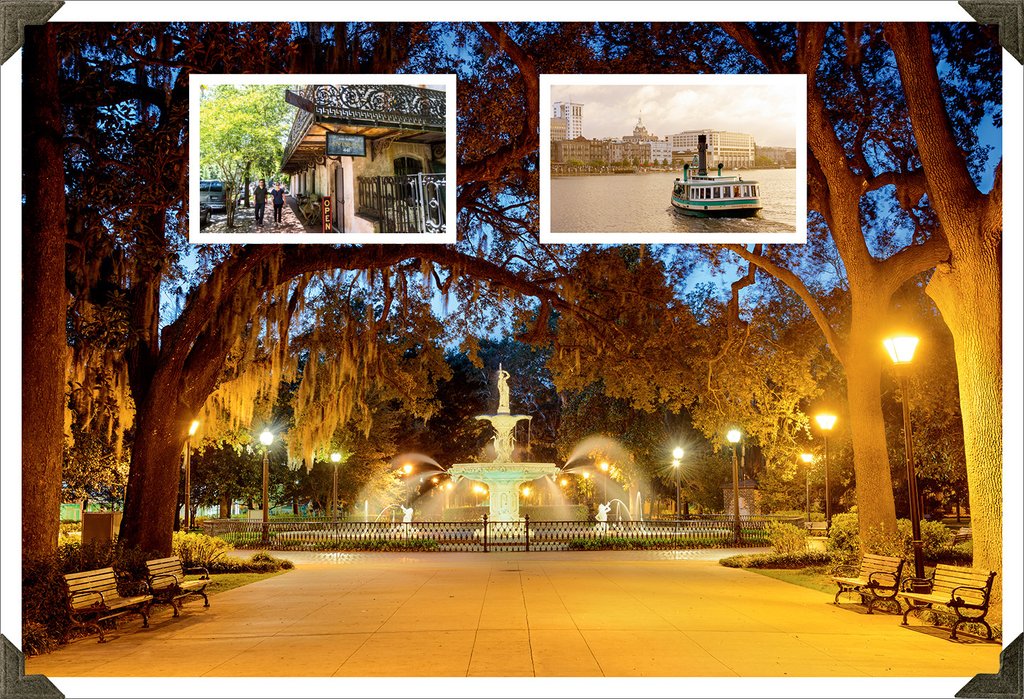

Photos: iStock/Sean Pavone (park) and Natalia Bratslavsky (ferry); Visit Savannah (street).

Oak trees towering overhead spread massive branches draped with Spanish moss; shaded underneath, azalea bushes are just beginning to drop their pink petals.

The stone bench we’ve chosen is cool to the touch in the southern heat.

We’ve been here only a few days but have quickly learned that the 2.5-square mile (6.5-square kilometre) Historic District of Savannah, Georgia, is a living museum.

An Architectural Array

One of the most colourful historical characters to step aboard was the pirate who gave us insight into the shanghaiing of young men at the tavern now known as The Pirates’ House. Having been plied with liquor, the unfortunate young men were dragged through a tunnel to the river and put aboard a ship, where they awoke to find themselves at sea and part of the crew. Apparently the practice inspired Robert Louis Stevenson to write Treasure Island.

We passed Chippewa Square, made famous in the eponymous movie by Forrest Gump and his box of chocolates. The Six Pence Pub on Bull Street was the set for scenes in Julia Roberts’s 1995 movie Something to Talk About. At Monterey Square, we learned that Jim Williams, who had actually lived in the Mercer Williams House, had been a dedicated private restorationist, responsible for saving and restoring more than 50 historic houses in Savannah and the surrounding Low Country.

Savannah was saved from the fires of the Civil War in the 1860s when prominent local businessmen persuaded the city government to surrender rather than let their city be burned to the ground, as Atlanta had been. Thanks to years of restoration, dedication, and fundraising by members of Historic Savannah and like-minded citizens, we discovered a historic district with a wonderfully diverse array of architectural styles from the 18th and 19th centuries.

The Davenport House, on Columbia Square, is an example of the Federal style. The Olde Pink House restaurant, on Reynolds Square, is a fine example of the symmetry of Georgian architecture. Gothic Revival can be seen in the Congregation Mickve Israel temple (founded in 1733), in Monterey Square, while the First Baptist Church (built between 1831 and 1833), on Chippewa Square, displays the Greek Revival style. The Telfair Academy, on Telfair Square, has the columns and alcove entranceways associated with Regency. The Hamilton-Turner Inn, in Lafayette Square, is an example of Second Empire style. Finally, the impressive Cotton Exchange building down by the river boasts Romanesque Revival. It is little wonder the famous Savannah College of Art and Design has its flagship campus in this city.

The Waterfront

Our hotel was a short walk from the waterfront, a good place to find an evening meal or a lively bar.

Savannah’s waterfront has been important from the beginning, originally for importing goods and exporting cotton from the colony of Georgia. The ornate red-brick Cotton Exchange building is still one of the most impressive structures on the banks of the Savannah River. We learned from our waitress that the present-day Cotton Exchange Seafood Grill and Tavern was a restored building that had been a huge warehouse for bales of cotton awaiting shipment by boat.

The next day, we explored the historic Factors Walks she’d told us about. In front of the line of former warehouses, black wrought iron footbridges arch from the buildings over a cobbled roadway below to the present-day sidewalk, which had formerly been a seawall. It was on these “factors walks” that cotton merchants of yesteryear stood to survey and bid on loads of cotton being driven past below. As in so much of Savannah, the old and the new tumble together. Today the Factors Walks carry foot traffic to the offices, shops, and restaurants located in the old refurbished warehouses.

A Port City

As we learned during a relaxing tour with Savannah Riverboat Cruises, the river and its port are still the lifeblood of Savannah—92 per cent of all goods move around the world in containers, and Savannah is the fourth-busiest port in the United States handling them. The port of Savannah contributes approximately $100 million a day to the economy of Georgia. The lovely old city and its port sit in a protected location 22.5 kilometres (14 miles) inland, and most surprising, it’s as far west as Cleveland, Ohio, a distinct economic advantage for importers and exporters.

The cruise turned around just past historic old Fort Jackson, where a cannon salute was fired, much to the glee of the children on board. On the way back, we got another view of the statue of the Waving Girl, which has become a modern symbol for this southern port city. Myth, history, and folk tale swirl around the story of Florence Martus, the girl who waved to every ship entering Savannah—and did so for 44 years, day and night. Some say she was waiting vainly for a sailor who had proposed to her—or was it simply her quirky obsession? Whatever the story, more than 1,000 sailors attended a birthday party at the Propeller Club thrown in her honour before she died.

The city of Savannah is a lovely sight from the river, with its riverside parks, historic warehouses lining River Street, and the golden dome of City Hall towering above it all. As the cruise boat docked, a sweet smell wafted our way from River Street Sweets—their world-famous pralines. The young men cooking up batches of the pecan-and-sugar candy happily handed out samples to the tourists flooding the shop.

City Market, between Franklin Square and Ellis Square, is another spot to sample pralines and other Savannah goodies. Within the four blocks are cafés for all tastes, oodles of craft shops, and many art galleries tucked into restored buildings—all watched over by the casual bronze statue of local lyricist and composer Johnny Mercer.

Mercer is portrayed leaning against a fire hydrant and looking up from a catalogue of songs, perhaps mentally composing the words to one of his many hits—including “Blues in the Night,” “One for My Baby,” “Lazy Bones,” “Fools Rush In,” “That Old Black Magic,” “Laura,” and “Moon River.” The soundtrack for Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil is like a Mercer tribute album, containing, as it does, 14 of his songs.

“Cradling Comfort”

Currently one of the most sought-after dinner reservations is at The Grey. A building that operated from 1938 to 1964 as a Greyhound bus station was transformed into this eclectic bar and dining room.

Creatively, it has touches of the past combined with a sleek, modern décor, referred to by the designers as “art deco meets transportation industrial.” For example, the bus station’s 24-hour diner was transformed into a quirky, busy bar offering booth and counter service. Like that of the dining room, its décor is stainless steel and stressed leather combined with remnants of the wonderful art deco style of its past life.

By the oyster bar, at the end of the glass-walled kitchen, is what was once the ticket window, and the depression in the terrazzo floor was created by thousands of feet standing in line. In the main dining room, gate numbers for bus bays of the past are still emblazoned on the wall. Diners are seated at the shiny new counter in the centre of the room or in booths around the perimeter.

My order of “sizzling smoky pig” turned out to be tender pulled pork topped with a fried egg and served in a cast iron pan with delicious cornbread on the side. It was a good example of what executive chef, Mashama Bailey, calls “the cradling comfort of Southern food.”

The Grey is a fun place to eat and the food is good. The bill is delivered with a vintage bus-related postcard. The chrome statue of a sitting greyhound has become the symbol of a culinary success story. However, as in so many popular eating spots in Savannah, a long wait for your reserved table is part of the experience.

Pass the Platters

Speaking of waiting, a unique spot well worth the wait is Mrs. Wilkes Dining Room. But plan ahead, go early, wear comfy shoes, and take a good book and a hearty appetite. What began in the 1940s as the dining room for Mrs. Wilkes Boarding House upstairs has grown into a not-to-be-missed southern food experience. Mrs. Wilkes serves only lunch and only from 11 until 2, Monday to Friday. There are no reservations and no credit cards. Hungry folks just stand in line, and depending on the day, that line can reach down the street and around the corner.

Inside you’ll find seven tables for 10 to be shared family-style by neighbours and tourists alike. Each table is covered in old-fashioned oilcloth and crowded with more than a dozen large bowls and platters of every imaginable vegetable, plus biscuits, gravies, sausage, meatloaf, stew, and Mrs. W.’s famous fried chicken. You may enter as strangers, but the camaraderie of passing the seemingly endless bowls and platters around the table soon has everyone chatting.

The highlight of the meal was the succulent southern fried chicken—the best we have ever tasted. It’s a family enterprise now run by Mrs. Wilkes’s granddaughter Marsha, and most staff have been there a long time. During her break, one of the cooks told us that she’d been cooking that delicious crispy chicken for 11 years.

All spring, the park grounds are a pageant of colour: wisteria and redbud in March, followed by the white, red, and pink blossoms of azalea bushes and the pink and white flowering dogwood trees of early April.

Each evening, we had come to enjoy the gentle sounds of busker Marion May’s saxophone drifting across Reynolds Square in the twilight, accompanying our walk back to the Planters Inn. In our hearts, we knew we would have to return and explore more of this seductive southern city.

Photos: Visit Savannah (all others) and geoffsphotos (Mercer Williams House); courtesy of the Planters Inn (hotel).