We’re a long way from beating cancer, but scientists are gaining ground. We’re highlighting some of the recent steps forward. This week: genetic testing and screening for depression.

By Wendy Haaf

More Genetic Testing

Scientists are also making inroads in better identifying women who are at high risk for developing breast or ovarian cancer due to inherited mutations in genes called BRCA1 and BRCA2. These mutations account for about five to 10 per cent of breast cancers and about 15 per cent of ovarian cancers.

Studies have found that women diagnosed with an advanced-grade ovarian cancer are rarely referred for genetic testing that ultimately could help their daughters and granddaughters.

“Levels of testing traditionally have been around 13 per cent,” Dr. Jacob McGee, a gynecologic oncologist and assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Western University’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry in London, ON. “That number should be close to 100 per cent.”

If a woman has one of these mutations, her close female relatives can also be tested. If they have one or both mutations, too, they can opt for surgery to remove the ovaries, “which could reduce their risk of all-cause premature death by 77 per cent and their risk of dying of an epithelial ovarian cancer by 96 per cent,” McGee explains. “But if you never test the patient who has cancer, you may never find out whether her daughter or granddaughter has a predisposition to developing that cancer.”

After conducting a study that confirmed the referral rate in their local centre was only 13 per cent, as per the overall rate, “we created a new process: patients with this high-grade serious ovarian cancer are automatically referred for genetic testing,” McGee says. “We’ve reached a consultation rate of over 90 per cent in just two years.”

More Help for Distress

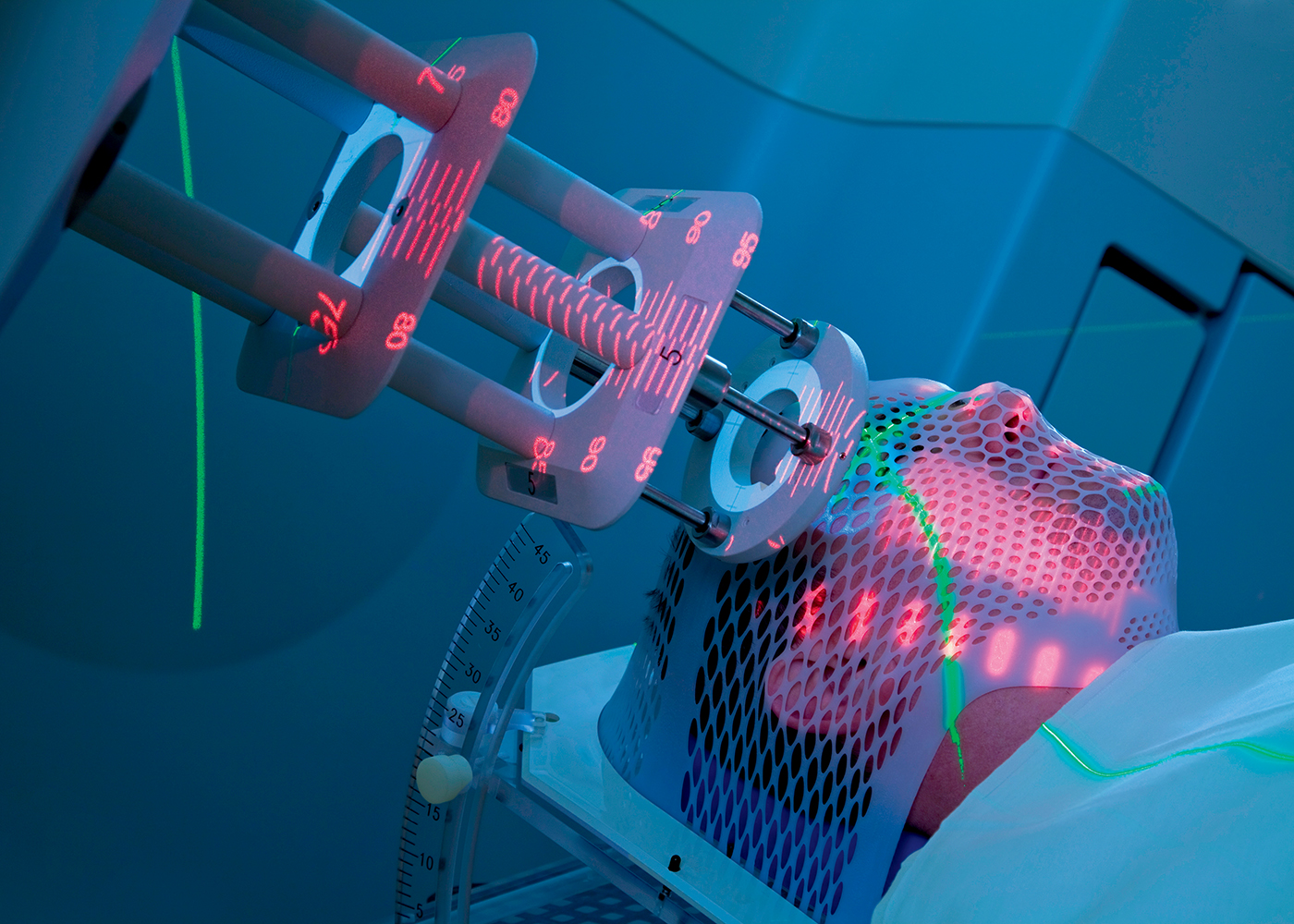

About 15 to 25 per cent of cancer patients develop depression, which not only impairs quality of life significantly, but can also affect a patient’s ability to consistently attend treatment sessions or take medications. While we have effective treatments for anxiety and depression, many patients still either don’t recognize they’re struggling or think they should be able to cope on their own.

Some health jurisdictions have therefore begun incorporating screening for depression into standard care for cancer patients.

“Ontario has implemented a provincial norm in terms of screening, so all hospitals should be screening for distress,” says Sophie Lebel, a psychology professor at the University of Ottawa.

People who score above a certain threshold are then assessed more thoroughly and, if necessary, connected with resources or referred for counselling.

“Sometimes people need only a few sessions,” Lebel says. “Research has shown that if you make this referral process a normal part of care, there’s a greater likelihood that people will take up the offer.”

Photo: iStock/Snowleopard1.